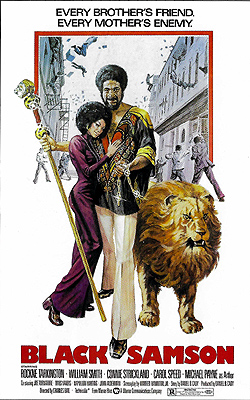

Black Samson (1974) -***½

Black Samson (1974) -***½

I had never even heard of Black Samson when it appeared on the lineup for B-Fest 2008. Then somebody on the B-Movie Message Board found the trailer on the internet, and posted a link to it; the moment I saw that, I realized that this movie had a fair chance of being the most magnificently silly thing I’d see during the entire festival. Among the most intensively loony action movies of the “hero with a gimmick” school that one could ask for, Black Samson pits a black-nationalist bar-owner with a pet lion and a humongous African walloping stick against the mafioso who seeks to open up his depressed neighborhood to the mob’s drug trade. And as absurd as it is, it somehow manages just a bit of narrative sophistication here and there, with a calculatedly “redeeming” social message a touch more credible than most and a certain amount of nuance in the characterization of the villains.

Our less-than-plausible hero (Rockne Tarkington, from Beware! The Blob and The Ice Pirates) is the proprietor of Samson’s, a divey neighborhood titty bar in some unidentified city’s black ghetto. Samson’s, incidentally, was plainly not built with topless dancers in mind; there’s no proper stage, and the girls must simply perform in any elevated spot where they can find three or four square feet of unobstructed area. The bar is apparently the community’s most popular hangout, for it’s packed on any given night with everybody from the expected slick jive cats to middle-aged ladies who look as though they’ve swung by for a drink and an ogle on the way home from their evening Bible-study class. Hell, you’ll even see the occasional white guy at Samson’s. One such man— Harry (Joe Tornatore, of Grotesque and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song) is his name— foolishly takes to harassing one of the dancers after he’s had four or five too many, and when he won’t desist no matter how directly Samson tells him to, the barkeep reaches under the counter for the Justice Stick, and proceeds to whale the living crap out of him. Harry has a friend along with him, but Giovanni Napa (William Smith, from Hammer and Invasion of the Bee Girls) wisely sits out the fight. This is not to say that Napa doesn’t have words with Samson once Harry is incapacitated, however, or that he means to let his buddy’s beating go unavenged.

This is a more serious development than it might seem at first glance. Obviously a six-foot, five-inch man who has both a lion and a stick can take care of himself, and the imperious manner in which Samson deals with Arthur the coke dealer (Michael Payne) shows that he feels no fear at all toward even career criminals. Giovanni Napa represents a threat of an altogether higher order than Arthur, however, for Napa is not merely a mafioso, but the nephew of mob boss Giuseppe Napa (Titos Vandis, from Satan’s Triangle and Genesis II). The area in which Samson’s is located is apparently the only one in the city where the Napa mob doesn’t yet control the drug trade, and Samson, having set himself up as a sort of benign modern equivalent to the traditional African Big Man, would surely pose an enormous obstacle to any mafia bid to close that gap. Giovanni hopes to use those two facts as a pretext upon which to convince his uncle to let him launch an offensive against Samson, but the old man isn’t buying it. Truth be told, the elder Napa is starting to look forward to his retirement (so what sort of pension package do you suppose the mafia has, anyway?), and he’s in no mood to go starting any wars. Beyond that, Giuseppe regards the gains to be had from adding Samson’s neighborhood to his empire to be too trivial to bother with in any case, and he refuses to commit the necessary men and money. If Giovanni wants to go after Samson with his own resources, that’s his business, but he’d better not come crying to Giuseppe for help if he gets himself into trouble.

Acting upon the assumption that any strong man’s greatest weakness is his woman, Giovanni begins his campaign by trying to bribe Samson’s girlfriend, Leslie (Carol Speed, of The Mack and The Big Bird Cage, done up with the most enormous unironic afro I’ve seen in all my life), into betraying him. This, incidentally, occurs at the very same moment that several of Napa’s boys are jumping Samson in an alley. Neither of these maneuvers accomplishes anything for Giovanni beyond cluing Samson in on whom he’s going to be grappling with for the remainder of the film, for Leslie is incorruptible and Samson is more than a match for any three mafia goons in a stand-up fight. Samson makes the next move, paying a visit to old Don Napa at his office, whereupon Giuseppe assures him that he has no designs on Samson’s ghetto, and that Giovanni is pursuing a vendetta of his own, without his uncle’s support. That’s got to be a blow to the younger Napa’s ego. For round two, Giovanni sends his crooked lawyer (John Alderman, from Love Camp 7 and Thar She Blows!) around with an offer to buy Samson out; Samson takes him up to the roof of the bar, and threatens— in an extremely credible manner, I might add— to throw him off. Nor does hiring black muscle from the ghetto gangs prove any more effective than siccing white enforcers on the troublesome barkeep.

Finally, Napa decides to play really dirty— he sends his own girlfriend, Tina (Connie Strickland, of Bummer! and The Centerfold Girls), over to Samson’s to audition as a dancer. With her in the bar every night, Giovanni figures some exploitable piece of information simply has to come to light. At the very least, Tina can use her charms to drive a wedge between Samson and Leslie, right? That last part might not actually need any help from Tina, though. Sure, Leslie is visibly jealous of the interest Samson shows in his newest dancer (there’s a faintly implied and all-too-brief critique here of blaxploitation’s tendency to treat white women not merely as sex objects, but as status symbols), but more than that, she’s worried sick that her boyfriend is setting himself up for a fall by playing hero the way he does. She wants him to sell the bar— even to Giovanni Napa, if that’s who wants to buy it— and skip town with her to someplace safe. Furthermore, she’s prepared to leave him if he refuses. If Samson’s determined to get himself killed, then Leslie doesn’t want to be around to see it happen. The upshot of this confrontation is the apparent breakup of the two lovers, followed by a meeting between Leslie and Samson’s old rival, Arthur, wherein Leslie offers herself to the pusher in exchange for him supporting Samson in the fight against Giovanni Napa. (Interestingly enough, Arthur turns out to have a day-job; even more interestingly, he’s a mortician!) Arthur turns Leslie down, preferring to ingratiate himself to the winner later, rather than risk forfeiting his current position by backing the losing side. He changes his mind, though, when some of Napa’s men abduct Leslie right out of his funeral parlor, killing his most trusted lieutenant in the process. Tina, too, gives her allegiance to Samson when Giovanni, in a transport of jealous, racist rage over the dalliance between her and Samson which he himself orchestrated, throws her from the back seat of his moving car, nearly getting her killed in the oncoming traffic. Giovanni Napa wants a war? Well he’s about to get one.

For most of its length, Black Samson is only slightly more interesting and entertaining than the typical blaxploitation flick, but it comes into its own most decisively during the showdown that begins when Samson goes to rescue Leslie from Napa’s warehouse headquarters. The rescue itself fails to live up to its potential by including no role whatsoever for Samson’s lion (which has been lounging, heavily sedated, on top of the bar since the very first scene), but the car chase that follows it is a thing of beauty, and the battle in a cul-de-sac of abandoned tenements that follows the chase is more beautiful still. Samson steals Napa’s Chrysler Newport to use as his getaway car (poking the Justice Stick up through the open sunroof, so that Napa and his men can’t possibly miss it), and the ensuing pursuit is rather like a car-wreck version of musical chairs. One mafia vehicle after another is destroyed in a succession of surprisingly well-choreographed crashes, but rather than admitting defeat, the gangsters inside the trashed automobiles immediately car-jack the next passing driver, and swipe their wheels to continue the chase. And unbeknownst to Napa, Samson’s object is not to get away from him, but to lead him into an ambush amid those condemned row houses, which his friends, neighbors, and customers have stripped of everything remotely usable as a missile weapon. When Napa thinks he has Samson trapped, all those people come out from their hiding places on the tenement roofs and begin raining random household junk— up to and including even the kitchen stoves!— down upon the gangsters’ heads. I don’t know about you, but I want to see a lot more movies now that climax with people throwing stoves at each other.

Cliche avoidance is a good thing, and there are quite a few cliches that Black Samson deftly sidesteps on the way to its demented conclusion. Although Giovanni Napa might be the most overblown villain in the entire blaxploitation canon (I mean, jeez— even Hoffo [the cartoonishly rat-bastardly mafioso in Slaughter] didn’t throw his girlfriend out of a moving car!), his uncle never steps up into the Final Boss bad-guy role one would expect of him. He tells Giovanni early on that he wants no part of his nephew’s feud with Samson, he tells Samson the very same thing a bit later, and in the end, he rather startlingly turns out to be as good as his word. Arthur stays true to his somewhat cowardly character even after he signs on as Samson’s ally, participating in the final fight on terms that are plainly calculated to expose him to as little personal danger as possible. The status of Samson’s relationship with Leslie remains tantalizingly unresolved in the end (remember, she had just broken up with him right before she was kidnapped), and as the credits roll, Samson seems to be much more interested in cementing his newly established friendship with Arthur than he is in patching things up with the woman he just spent so much time and effort rescuing. Of the greatest importance, Samson is an unusual hero for a movie of this type, even leaving aside the doped-up lion and the Justice Stick. I don’t think I’ve seen any other blaxploitation film willing to give a black nationalist so much credit. Samson is a far cry from Ben Buford and his followers in Shaft, who were portrayed as being good for cannon fodder, but not much else, yet when he talks yearningly about “our people,” he very obviously means it. He is something one only rarely sees in a mainstream-studio movie: an effectual counterculture idealist. Now, one could complain that this aspect of Samson’s character is paper-thin, and that its handling suggests that the filmmakers had only the dimmest understanding of what black nationalism might mean— and one would be right. But the fact remains that screenwriter Warren Hamilton Jr. (to say nothing of the bosses at Warner Brothers) was willing to base a movie around an advocate of an idea-system that was widely perceived at the time to be incredibly threatening, and to treat him as a full-fledged hero. No matter how foolish this movie may be in sum, that much about it remains extremely laudable.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact