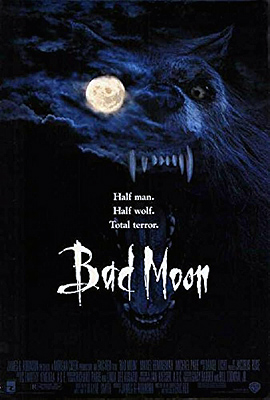

Bad Moon (1996) **

Bad Moon (1996) **

When writer/director Eric Red (best known for his scripting work on The Hitcher and Near Dark) finished reading Wayne Smith’s novel, Thor, he thought it was the most original idea for a werewolf story that he’d ever encountered. That’s probably fair, too, since I certainly can’t think of another one told mainly from the perspective of a family dog defending its humans from a monster with which it has more than a little in common. But Bad Moon, the movie Red made from Thor once he’d secured the adaptation rights, is a terrible disappointment, even if it narrowly avoids being a terrible film. The dog is great— which is crucial, since he’s really the star of the show. The wolf-man is usually great, too, as both a special effect and a credible physical threat. Even the pre-teen boy in the endangered family is pretty good more often than not. But the adult humans are washouts across the board, and even worse, Red can’t make up his mind whether the werewolf in his human guise is more Larry Talbot or Eddie the Mangler. That isn’t a point on which you can split the difference intelligibly— and even if you somehow found a way, it still wouldn’t be a characterization that you could entrust to an actor as limited as Michael Paré.

A documentarian or telejournalist or something by the name of Ted (the aforementioned Paré, from Tales of an Ancient Empire and Bloodrayne) is out in some mountainous jungle nowhere to film… well, actually it never comes up, because it doesn’t really matter anyway. What does matter is that the assignment is at an end, and tomorrow Ted can begin trekking back to the land of hot showers, soft beds, and no fucking mosquitoes. He’s enjoying a celebratory fuck with his colleague/girlfriend, Marjorie (Johanna Marlowe), when a goddamned werewolf infiltrates their campsite. This doesn’t even look like the kind of country that would be frequented by regular wolves! The monster rips open the couple’s tent, and lifts Marjorie right off of Ted in mid-screw. The man responds much faster than most of us probably would under the circumstances, but a fat lot of good it does him. Ted takes a non-fatal but serious mauling during his initial counterattack, and by the time he recovers enough to line up the pistol shot that blows the werewolf’s head off, Marjorie looks like something you’d find in the display cooler at a halal butcher shop.

Months later, in what I take to be the Pacific Northwest, a liability lawsuit scammer (the astonishingly named Hrothgar Mathews, of Severed and Cloned) is casing a moderately wealthy neighborhood for suckers. You know— somebody whose BMW he can step out in front of while it’s moving too slowly to inflict worse than a bruise or a scrape, or maybe a house with some freshly-dug fencepost holes in which he can pretend to sprain his ankle. Then he’ll make threatening noises about suing, the mark will get scared enough to pay him a few grand to go away, and he’ll buy that big-screen TV for the den in his basement or whatever. The asshole thinks he’s found what he’s looking for in Janet (Mariel Hemmingway, from Lipstick and Deception II: Edge of Deception), a lady whose impressively big house sits on a huge, wooded lot, and whose German shepherd, Thor, he annoys into tackling him. He wasn’t figuring on Janet being a high-powered lawyer, however, and the ensuing conversation goes not at all the way he expected. Even his threats to involve the sheriff glance right off of the woman’s steely composure, for it also happens that Sheriff Jenson (Ken Pogue, of The Neptune Factor and The 6th Day) is a friend of hers from work. Perhaps the scammer would like her to call Jenson for him? Recognizing at last that he’s well and truly lost the game, Janet’s uninvited guest withdraws, huffing and puffing his phony outrage all the way.

Despite all appearances to the contrary, there is an organic connection between the events in that Cascade Mountains driveway and those in the werewolf-haunted jungle, because Janet and Ted are siblings. They’re pretty close siblings, too— close enough, anyway, that Janet’s son, Brett (Gattaca’s Mason Gamble), always gets excited at the prospect of a visit from Uncle Ted. That being the case, Janet is both pleased to get a phone call from her brother shortly after the scammer incident, and a little put out when he mentions that he’s not only been back in the States for a matter of months, but has actually been living out of an Airstream trailer beside a lake not far from her neighborhood. Nor does Janet know what to make of Ted’s guarded demeanor when she and Brett drive out to visit him soon after he renews contact, or of the way he blows off her invitation to park his trailer in her backyard instead. But since we know what conventionally happens to people who survive being injured by werewolves, we’ll naturally take those anomalous behaviors as confirmation of what we already suspected. Furthermore, it quickly becomes apparent that Ted has not been a good doggy out on that lake. Thor wanders off into the woods in pursuit of an interesting scent while the humans are catching up, and finds a tree in which something— like, say, a werewolf— had stashed the mostly-eaten body of a hiker. Neither of the dog’s owners paid any heed to his sniffing about, however, so Janet and Brett go home none the wiser late that afternoon.

Then that night, a forester taking tree-growth measurements (stuntman Gavin Buhr, in a closer approach to acting than he was usually called upon to make) is waylaid by a monster very much like the one that attacked Ted’s jungle campsite, and any remaining doubts we might have about his lycanthropy drain away with the ranger’s spilled blood. Naturally the forester’s employers knew where he was and what he was doing when he disappeared, so not many hours elapse after sunrise before the woods are crawling with searchers. Once they find what’s left of the ranger, they don’t take much longer to discover the corpse that Thor sniffed out earlier, and the next thing Ted knows, he’s up to his eyeballs in cops digging human remains out of the woods around the lake. Incredibly, none of those policemen seem to consider him a suspect yet, but he sensibly calls Janet back to say that he’s decided to accept her invitation to relocate after all.

Bad Moon settles into the first of a couple intriguing grooves at this point, functioning a bit like a lycanthropic variation on Shadow of a Doubt. Here, though, it’s Thor in the role of the one “person” who suspects that the beloved visiting relative might be more than he seems. The dog isn’t aggressive with Ted exactly, but he unmistakably treats him as both a potential rival and a fellow canine. Thor pisses on the Airstream’s wheels. He parks himself outside Ted’s door to start each morning with a dominance-establishing staring contest. Above all, Thor acts visibly wary whenever Ted gets too close to either Janet or Brett. It’s enough to make Janet wonder if there’s something the matter with her pet.

That’s when the lawsuit scammer comes back for an encore. No, he hasn’t thought of a new grift to try on Janet— this time, he’s strictly out for revenge. Having ascertained that Thor spends his nights in a doghouse out back, the big creep figures he’ll assuage his wounded pride by braining the dog with a meat cleaver. Once again, though, he’s failed to account for a crucial detail, which is that Ted is listening to the Call of the Wild when he sneaks onto the property to wreak his vengeance. It’s the scammer who winds up in pieces, and since wolf-men aren’t particular about cleaning up after themselves beyond maybe dragging a victim back to their lair to finish eating later, the signs of a sanguinary struggle are unmistakable in the morning. Jenson’s deputies soon find the body (they’ve had a lot of practice lately, after all) and the sheriff makes the plausible deduction that the scammer found Thor too much to handle. Any dog that would kill a man so viciously, even in a fight for its life, is too dangerous for human company, and before Brett knows what’s happening, the deputies are hauling Thor off to the pound to be put down. That’s as inconvenient as it is traumatic, because it’s just about then that Janet finds Ted’s werewolf diary in his trailer. Mind you, she doesn’t take it literally for what it is, but the realization that her brother has become a serial killer is hardly less horrific than the realization that he’s become a skin-changing monster. Sure would be nice to have a big, fearsome dog around the place right about now, huh?

We live in an era when obsessive fixation on lore has become a blight on virtually all popular media, but there are circumstances in which it really is of great importance to get lore “right,” and then to stick to it. When you’re writing about werewolves in particular, to decide how lycanthropy works is tantamount to deciding what story you’re going to tell. In establishing what drives the change, how or indeed whether the condition is transmissible, what degree of influence the human and animal guises have over each other, and so forth, you establish as well the man’s culpability for the monster’s actions, and everything that follows from there. A witch who transforms at will into a beast by donning an enchanted wolfskin is an altogether different proposition from some poor schmuck who caught magic rabies. Similarly, a werewolf whose human and animal selves are functionally two separate entities is an altogether different proposition from one whose personality is always a little bit lupine, but also maintains at least some awareness of their human goals and relationships no matter how furry they become. In Bad Moon, Eric Red shirked that step in the writing process, and the finished film is critically compromised as a result.

At least at first, you see, Red positions Ted as basically a tragic victim. The prologue shows him to be a brave man, and his sister and nephew talk about him as if he’s a good one as well. His trailer is filled with herb samples and medical paraphernalia suggesting that he’s worked very hard over the months since he became infected to find some way, be it scientific or magical, to cure his lycanthropy, and he consistently tries to restrain himself with fetters and handcuffs before the change comes over him. Even Ted’s seemingly reckless decision to park his Airstream on Janet’s land is as much an attempt to regain his full humanity as a bid to dodge responsibility for his animal self’s crimes, for Bad Moon takes a cue from The Curse of the Werewolf by positing the love of family as a potential counteractive to Ted’s supernatural affliction. The beast will not be denied, however, resisting every folk nostrum and escaping its bonds more often than not. So far, so good. But right about when Thor gets carted off to the pound, the human Ted undergoes a transformation almost as drastic as his nightly descents into animalistic savagery. Without warning or apparent cause, he starts acting like a somewhat muted copy of Robert De Niro’s Max Cady in the then-recent Cape Fear remake. To be sure, a lycanthropic take on the 1990’s Wealthy White People in Peril plot template appeals to me almost as much as a lycanthropic Shadow of a Doubt, but it would require far more work than Eric Red ever does in this film to build that concept around the tragic werewolf that Ted starts off being. Ironically, the best way to do it would probably be the one that Red explicitly rejects here, having Ted’s monstrousness wax and wane with the phases of the moon in the manner of Silver Bullet. (And while we’re on that subject, how fucking ridiculous is it to detach lycanthropy from the lunar cycle in a film called Bad Moon?!)

Mind you, even in that best-case scenario for justifying Ted’s personality shift, Bad Moon would still run up against Michael Paré. It’s funny. I have seen Paré be good from time to time, most notably in Streets of Fire. But that movie doesn’t have characters so much as it has archetypes: the Misunderstood Badass of Few Words, the Tough but Fair Lawman, the Rich Little Weasel, etc. Maybe Paré’s strong suit was to match himself to some instantly recognizable universal figure, so that audience familiarity with what he was playing could fill in all the blanks in whom he was playing. If so, the role of Ted affords him no such cheat code, and his performance is dead on arrival. Still, even Paré is better than Mariel Hemmingway, who acts like she’s living out one of those dreams about having to take a final exam in a class that she never once attended. I halfway wonder whether she ever looked at a copy of each day’s script pages before arriving on set.

Against all that, the main upside to Bad Moon, believe it or not, is Thor. Partly I mean that on a conceptual level. This movie derives a strange frisson from its incongruence with what it usually means in American cinema for a dog to be the hero. From the moment I realized what the title of the source novel had to signify, I watched on tenterhooks, waiting constantly for Bad Moon to lose itself in a twisted version of kidvid. But although there are several points in the film at which that almost happens, it never truly does. Meanwhile, if we disregard the expectations engendered by Benji, Lassie, and Rin Tin Tin, it really is a rather brilliant idea to pit a werewolf against a large, powerful dog, framing the conflict from both sides in terms of canine psychology. Bad Moon never lives up to that potential, of course, but to my considerable surprise, it makes a consistent, good-faith effort to do so. That’s a lot more than I was expecting. What really makes Bad Moon worth watching in spite of itself, though, is the actual performance of the actual dog. Strictly speaking, there were several dogs, as there so often are in these situations: stunt-trained animals for the fight scenes, a body double for scenes that required no more than that Thor be visible somewhere in the frame, and the main “actor” dog. The latter’s name was Primo, and honestly, I’m doing him a disservice by putting quotation marks around “actor.” He’s in the same league as Tiger and Jed, the scene-stealingly gifted canine performers in A Boy and His Dog and The Thing respectively, especially with regard to his facial expressions. The key point is that Thor is supposed to be bewildered by this human who gives off the scent signals of a wolf, and I simply cannot imagine how Primo’s trainers were able to elicit from him that specific vibe of wary uncertainty. Heaven knows Eric Red was unable to coax anything comparable out of the humans in the cast!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact