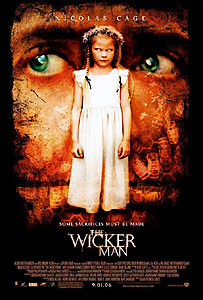

The Wicker Man (2006) -***½

The Wicker Man (2006) -***½

Remaking The Wicker Man was a stupid idea. The original was essentially perfect (at least in the longer of the two cuts available today), so there was nothing to be credibly gained from doing it over unless possibly the aim were to reconstruct the lost half-hour that supposedly lies entombed beneath the segment of the M3 motorway that passes in front of Shepperton Studios. But beyond that, The Wicker Man is so tightly bound to the time and place in which it was made that even to attempt transplanting it out of that context strongly implies that one has missed the entire point of the film. Neil LaBute, writer and director of the 2006 Wicker Man, did indeed miss the point; every second of his version shouts his point-missing from the rooftops, and therein lies the greater part of this movie’s potentially substantial entertainment value. To a viewer unacquainted with Anthony Shaffer and Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man, LaBute’s might look like just another bad 21st-century horror film (although surely anyone can appreciate the cinemasochistic delights of a fully manic Nicholas Cage punching women in the face while dressed as a bear). Fans of the original, however, will experience a delirious species of déjà vu, as LaBute recapitulates nearly every beat and twist of Shaffer and Hardy’s masterpiece in crass and witless form. More than a predictably lousy remake, LaBute has given us Bizarro Wicker Man, a superbly brilliant and powerful movie’s fumbling idiot doppelganger.

In outline, the 2006 Wicker Man’s story is remarkably close to that of its predecessor. California-based motorcycle patrolman Edward Malus (Cage, who also brought his unique brand of crazy to Ghost Rider and Drive Angry) receives a letter describing the disappearance of a little girl named Rowan Woodward (Erika Shaye Gair, from Whispers and White Noise 2: The Light) from the isolated agrarian community of Summersisle, on a privately-owned island in Puget Sound. Malus travels to Summersisle in quest of the vanished child, but finds instead a nest of hostile neo-pagans. The clues Malus uncovers lead him around in increasingly frustrating circles, climaxing when he receives permission to dig up Rowan’s supposed grave from Sister Summersisle (The Exorcist’s Ellen Burstyn, whose standards have apparently fallen sharply since the day she refused participation in Exorcist II: The Heretic), the head of the commune, and discovers that the coffin contains only a burned-up doll which Willow (Kate Beahan, of Lost Souls and The Matrix: Revolutions), the girl’s mother, identifies as having belonged to Rowan. Eventually, Malus concludes that Rowan is being held for impending sacrifice in the hope of propitiating the Great Mother Goddess and reversing thereby a recent downturn in Summersisle’s agricultural fortunes. And in the end, he learns to his immense disadvantage that his surmise was only half-right. Even most of the individual steps carrying Malus from Point A to Point Fucked are the same as those trod by Sergeant Howie a generation before. There’s still a shady schoolteacher (Molly Parker, of The Substitute and Intensity) whose pupils are transparently in on the plot. There’s still an even shadier doctor (Frances Conroy, from The Seeker: The Dark Is Rising) who plies the visiting policeman with bullshit about how and when Rowan supposedly died. There’s still a grouchy-as-fuck innkeeper (Diane Delano, from Sleepwalkers and Jeepers Creepers II) whose winsome, blonde daughter (Leelee Sobieski, of Deep Impact and Joyride) has sinister motives for her pattern-breaking friendliness toward the cop. Photos of last year’s harvest festival even figure once again as a vital clue. And of course it could scarcely be The Wicker Man if the cultists’ protocol for human sacrifice were not largely identical to what we saw in the original film.

As the saying goes, however, the Devil (or the angry Great Mother Goddess, as the case may be) is in the details. The starkest illustration of the difference between the two movies’ approaches is on display during their respective versions of the classroom scene. When Sergeant Howie looked inside Rowan Morrison’s vacant desk in 1973, he found a beetle within, tied by one of its tarsi to a nail at the center of the storage-compartment floor so that its efforts to crawl out of the trap merely turned it around in a spiral that bound it ever more securely instead. It was a subtly disquieting moment; between the inventiveness of the children’s cruelty and the teacher’s offhand toleration of same, it was the first real hint that Summerisle’s morality might differ from Howie’s in ways more menacing than the islanders’ relaxed attitudes toward sexuality. And in retrospect, it served as a teasing clue to what awaited the sergeant come May Day— he was the beetle, and his dogged search for Rowan was the thread with which he progressively ensnared himself. It isn’t a beetle trapped inside Rowan Woodward’s desk, though, nor is there anything subtle about what happens when Malus opens it up. Far more enterprising in their efforts to unnerve the interloper, Summersisle’s youngsters have somehow managed to stuff a full-grown crow into that desk! In reviewing the original Wicker Man, I commented upon the remarkable confidence with which it held its horror in abeyance, trusting the mystery of Rowan’s disappearance and the intellectual sparring between Howie and the islanders to hold the viewer’s attention until it was time to bring the hammer down. LaBute, in sharp contrast, apparently envisioned an audience of hyper-caffeinated nitwits, and so he transforms a moment of quiet unease into a JUMP SCARE! Don’t bother looking for allegorical significance in the imprisoned crow, either. The foreshadowing of Malus’s fate is handled instead by a thuddingly obvious exchange of dialogue between him and Sister Rose the teacher on the meaning of the word, “quixotic.” The poor bird has nothing whatsoever to do but to make a lot of noise and to fill our heads with hilarious visions of what those kids must have gone through to manhandle him into confinement. It’s a wonder half the class isn’t out recovering from their injuries!

The whole movie is like that in one way or another, so that a comparison between the two versions is like one of those “Goofus and Gallant” cartoons they used to run (and might still, for all I know) in Highlights for Children. Anthony Shaffer and Robin Hardy meticulously researched Celtic religious practices to provide the basis for their pagan cult; Neil LaBute randomly mixes and matches elements of Wicca, Amish practice, and the Quiverfull movement, then gender-flips the social power dynamics to yield something out of Rush Limbaugh’s most paranoid fantasies of what college girls are taught in women’s studies courses. Shaffer and Hardy tied the origins of Summerisle into the real-world social, political, and economic conditions of 19th-century Britain; LaBute makes up a bunch of bullshit about a hitherto-unsuspected pre-Christian community of matriarchal apiculturists who pattern their society after that of the honeybees on which they depend, and who fled successive waves of Christian persecution until they wound up in Oregon Country in the 1830’s. Shaffer and Hardy brought Howie to Summerisle in the ordinary course of his duties as an officer of the law; LaBute posits a ludicrous chain of conspiratorial contrivances involving a grisly staged traffic accident, a mole in Malus’s police department, and a prior connection between Malus and Willow, apparently because the idea of a cop just doing his fucking job was too hard to swallow. (And strictly speaking, looking for Rowan isn’t Malus’s job, anyway. Summersisle is in Washington, where the California Highway Patrol has no authority. Yet somehow it never crosses Edward’s mind to show Willow’s letter to the cops in Seattle, who would be within their jurisdiction to launch an investigation on the island. Which reminds me— Shaffer and Hardy made their “remote agrarian community” meaningfully remote; LaBute situates his a quick hop by plane or a couple hours’ boat ride from fucking Seattle!) Shaffer and Hardy had the islanders obstruct Howie’s investigation in subtle, confounding ways, so that they seemed always to be cooperating while they did the exact opposite; LaBute makes them openly and belligerently unhelpful, so that Malus’s lack of legitimate authority is the only thing that can explain why the whole population of Summersisle isn’t under arrest by the middle of the second act. I could go on, but you get the point.

The most inexcusable dumbing down that LaBute commits, however, concerns the terms of the struggle between Malus and the cult, and this is what I was mostly talking about when I said that LaBute had completely missed the point of The Wicker Man. I devoted roughly a quarter of my review of the original to discussing its theological implications, so I won’t go into them again here. It will suffice for my present purposes to observe that the Shaffer-Hardy version had theological implications, that its creators understood those implications, and that they went so far, in fact, as to make them the centerpiece of the film. The LaBute Wicker Man, meanwhile, has a great, gaping void at its core, because unlike Sergeant Howie, Edward Malus doesn’t believe in anything. He comes to Summersisle not as the representative of an antithetical creed, but as a mere outsider. Sure, Malus thinks the islanders are a bunch of loonies, but in thinking that, he expresses no more than the instinctive disdain that members of the social mainstream typically feel for a committed counterculture. Had Summersisle been instead a colony of health-food fanatics, Goreans, or Jehovah’s Witnesses, Malus would no doubt have responded the very same way. Sister Summersisle and her people, then, are fighting a battle of faiths against an unarmed opponent, and The Wicker Man is thus reduced to simple backwoods horror.

Just the same, I kind of love this piece of shit. I mean, how many movies can you think of in which a pagan religious ritual is presented in such a way as to make you appreciate the dignity and good taste inherent in Christopher Lee leading a procession by dancing down the road dressed as Cher? How many movies think being burned alive isn’t horrifying enough for today’s sophisticated audiences, and compensate by having the victim both hobbled and stung into anaphylactic shock by angry bees first? How many movies have you seen in which a fully manic Nicholas Cage putting on a bear costume and punching women in the face would have stiff competition for the title of Silliest Thing to Happen? Movies in the 21st century thus far have been disappointingly short on utterly bonkers bullshit, but The Wicker Man has enough to make up for quite a few mundanely bad films all by itself.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact