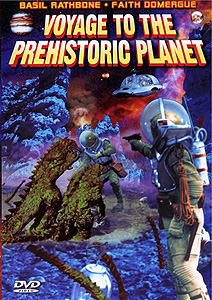

Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet/ Voyage to a Prehistoric Planet / Prehistoric Planet (1965) **½

Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet/ Voyage to a Prehistoric Planet / Prehistoric Planet (1965) **½

During the 1960’s, American International Pictures really started living up to their name. In addition to shooting an increasing percentage of their own films overseas, AIP began importing huge quantities of foreign product— particularly after 1965, when the studio got into the TV business, and encountered for the first time the voracious appetite of small-screen audiences for programming of any and every type. They brought over monster movies from Asia, costume epics and gothic horror films from Italy, thrillers and crime dramas from Germany, Bond-wannabe spy pictures from wherever they were being made. Remarkably, AIP even extended its probing tentacles behind the Iron Curtain, when Roger Corman cut a deal with the Soviet Sovexportfilm agency to purchase a handful of fantasy and science-fiction movies. Obviously, the political situation in the mid-1960’s precluded the American studio from simply dubbing the Russian imports and releasing them as-is— even leaving aside the openly anti-American tone of the sci-fi disaster flick The Heavens Call, for example, three years after the Cuban Missile Crisis was a little too early yet to expect US audiences to acquire a taste for Bolshevik cinema. Consequently, American International used Corman’s Soviet holdings more as a source of stock footage than anything else; The Heavens Call was stripped down to little more than its special effects sequences and then totally rewritten to become Battle Beyond the Sun, while A Dream Comes True was raided for effects footage with which to dress up Queen of Blood. Planet of Storms, however, emerged from the cutting room relatively intact, at least the first time around (more on this later). Though it suffered the usual condescensions of utterly atrocious dubbing and the insertion of new American “stars” whose actions have strangely little evident effect on the story, and though it somehow seems that a good portion of the original point has been mislaid somewhere, Planet of Storms’ transformation into Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet accomplishes a bit more than merely to make me want to see the original Russian film. Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet is honestly pretty entertaining in its own right, despite being obviously dated, even by the standards of 1965.

Late in the first quarter of the 21st Century, an international effort is underway to land astronauts from a squadron of three rocketships on the surface of Venus. The mission is being run from moon base Lunar 7 by the man who has planned it from its opening stages, Professor Hartman (Basil Rathbone, from Fingers at the Window and The Magic Sword); command in the field belongs to Brendan Lockhart (I Was a Sputnik of the Sun’s Vladimir Yemelyanov— and note that none of the Russian players are identified by their proper names in Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet’s credits) of the spaceship Vega, while the top scientific posts are those of Dr. Kern (Georgi Teikh, from Solaris) and Marsha Evans (Faith Domergue, of It Came from Beneath the Sea and Cult of the Cobra), both aboard the Sirius. Complications arise almost immediately, when the third ship, the Catella, is struck by an asteroid and obliterated. Hartman initially wants to postpone the landing until reinforcements arrive from home, but Vega pilot Andre Ferneau (Gennadi Vernov) pushes for something bolder. Ferneau wins his companions over swiftly, and after a bit of number-crunching by Kern’s robot, John, Dr. Evans is able to sell Hartman on a new plan. She will remain in orbit aboard the Sirius, while Kern, the robot, and Allen Sherman (Yuri Sarantsev, from The Aquanauts and The Ghosts of the Green Room), the third Sirius crewman, descend to the surface in their ship’s auxiliary landing craft. After they’ve determined the safety of the landing site, the Vega will set down as well, and the mission can get started in earnest. Again, things don’t go precisely as planned. The lander drifts off-course during the descent, and loses contact with the orbiting mothership. Lockhart makes the decision to follow them down and effect a rescue when contact cannot be restored even after the Vega’s orbit returns it to the optimal sky-arc for radio transmission, leaving Marsha alone to maintain the link with Lunar 7.

The Vega at least makes its landing in safety. Venus proves to be a rugged, inhospitable place, wracked by harsh weather and inhabited by a menagerie of dangerous, mostly reptilian creatures. Something that resembles a huge, carnivorous plant attacks Ferneau almost instantly upon his stepping outside the ship, and it takes both Lockhart and Hans Walters (The Road to Saturn’s Georgi Zhyonov) to wrest him loose from its clutching tendrils. And while none of their companions are aware of this just now, Kern and Sherman are in even bigger trouble, their landing site in the swamps besieged by savage, humanoid lizards. Only the strength and resilience of John the robot enables them to fight their way clear to the dry ground of the overlooking hills. Luckily, Marsha detects their movements from orbit, and dispatches the Vega crew in their direction. Much of the next hour is devoted to the two parties’ perilous journeys across the Venusian countryside, first toward their rendezvous point and then back to the Vega’s landing site. On the way, the Vega crew encounter a drowsy sauropod, get dive-bombed by a giant pterosaur while crossing a small sea in their hovercar, and must finish their trek on the sea’s floor rather than its surface when the latter monster refuses to leave them alone even in the face of gunfire. While submerged, Lockhart, Walters, and Furneau discover an idol-like bronze statue of a winged reptile like the one that drove them underwater, proving incontrovertibly that Venus harbored intelligent life at least sometime during its history, and putting an altogether different spin on the mysterious sound they keep hearing in the distance— a sound which Ferneau has said from the start reminds him of a girl singing. Kern and Sherman, meanwhile, are opposed less by the wildlife than by the elements, facing floods, torn spacesuits, and even a volcanic eruption. The Vega crew’s hovercar reaches them just moments before John (who has been holding his human companions up above a deadly lava flow) is consumed by the molten rock. The astronauts never do manage to reach what looks like a city in the mountains, nor do they ever make contact with the mysterious singer. But before they are forced to leave Venus by seismic activity threatening the Vega’s landing site, Ferneau finds strong evidence that the planet’s unseen, pterosaur-worshiping inhabitants are not just intelligent, but human-like as well.

By 1965, Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet was something of an anachronism, being little more than an update of The Angry Red Planet, without a framing story and with the astronauts flying off in the opposite direction from Earth. Naturally, it seems even further behind the times today, but it retains considerably greater interest than the similarly backward-looking sci-fi films which AIP was producing from the ground up at the time, due mostly to the distinctive design of the sets and props and the unexpectedly lavish production values it inherited from Planet of Storms (and, to a lesser extent, from The Heavens Call, whence came the gorgeous space station footage in the first act). Unlike Hollywood, the Russians in the 1960’s weren’t entrusting their science-fiction movies to the shabbiest and most underfunded outfits within their cinema industry. Films like Planet of Storms were prestige productions, meant to instill respect and admiration for the nation’s space program (which still had a strong claim to be foremost in the world in those days), and to stoke the fires of inspiration which would drive the next generation of Soviet space scientists and explorers on to even greater heights. By modern standards, this movie looks cheap and clunky, of course, but in comparison to such contemporary American productions as Journey to the Seventh Planet or Robinson Crusoe on Mars, Planet of Storms— and by extension, Voyage to the Prehistoric Planet— is quite an achievement, technically speaking. Lord knows AIP got more for their money by buying the work of Sovexportfilm than they could ever have had within the limits of their own resources.

AIP unfortunately enjoyed a bit less success in reworking the Russian footage than they did in simply presenting it. The rewritten dialogue is remarkably inane, and the drastic difference between the natural cadences of English and Russian as spoken languages is such that the scrupulous efforts to make the voiceovers line up with the mouth movements frequently result in syntax so tortured as to shame even a police chief or a politician. And of course there’s just no getting around the fact that nominal stars Basil Rathbone and Faith Domergue have nothing whatsoever to do with the plot, trapped as they are in footage shot three years later on the opposite side of the globe. Indeed, all that can really be said in favor of US-lensed inserts is that it was a smart move to post-loop the dialogue— it helps a bit that Rathbone and Domergue are just as obviously dubbed as all the Russians tramping around on Venus and contributing meaningfully to the story. Ultimately, what Roger Corman protégé Curtis Harrington has made out of Planet of Storms is stylish and inoffensive, but also mostly empty. American International wasn’t quite finished with Planet of Storms yet, however. Two years later, Henry Ney and Peter Bogdanovich (the latter hiding behind the pseudonym “Derek Thomas”) would recut the Russian footage yet again, adding still more revised dialogue and a different set of familiar faces in curiously self-contained subplots to create Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women. But that’s another story altogether…

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact