Us (2019) **½

Us (2019) **½

In Scandinavia, people used to believe in beings called hulders. They were among the local variants on the pan-European theme of a hidden race living under the ground and in wild areas seldom visited by humans, akin to elves, fairies, dwarves, trolls, leprechauns, and the rest of that lot. Hulders also had points in common with geophysically or territorially bound nature spirits like nymphs and dryads, since they were often assumed to guard over a particular valley, hill, grove, etc. The female of the species was usually said to be beautiful (so long as you don’t mind an animal tail or a back skinned with tree bark) and seductive, prone to bewitching careless young men who strayed into their territory, while the males— called hulderkarls— were twisted and ugly, and preferred to stay out of sight. Those who fell under the hulder’s spell were subject to a variety of fates ranging from unspeakable to downright pleasant. On the whole, though, it was reckoned best to have as little to do with the creatures as possible. Naturally, the longer belief in hulders persisted, and the farther it spread among relatively isolated communities, the more variations appeared, some drifting far indeed from the original conception. One later version from Norway has it that the hulders are an entire race of malevolent doppelgangers. We each have one, a distorted copy of ourselves living somewhere under the ground, waiting for the opportunity to kidnap and replace us. The best trick of all, so far as this breed of hulder is concerned, is to substitute one of their newborns for his or her surface-dwelling double, to be raised from the cradle as an imposter. These changeling-hulders fear scissors and shears, though, so they can be warded off by hanging a pair over your child’s bed at night. It’s an unsettling idea to ponder, even despite the somewhat goofy traditional countermeasure— that there’s another you lurking in some subterranean cavern, aware of your existence and forever scheming, half-mad with envy, to usurp your identity and take your place.

Abraham Lincoln, to the best of my knowledge, never met a hulder— neither the child-stealing variety nor the woodsman-seducing variety. He did, however, face down a monster considerably more horrid, and was ultimately destroyed by it. What’s more, having been dealt the shit hand of presiding over a nation in the process of tearing itself apart, he had the almost absurd courage to ante up for a second go-round when his first term ended with the Civil War still raging. Lincoln was by then waging a very different conflict from the one that erupted under his ass a month after his inauguration, however. Although the South had always been fighting to preserve slavery, the North initially cared less about ending it than about enforcing the permanence of the constitutional union. After all, there were a couple slave states that didn’t follow South Carolina into secession, and it seemed unwise given the realities on the ground in 1861 to antagonize their voters. By 1864, however, public opinion throughout the Union had shifted to match the Confederate view of the war, so that the main Northern objective was reconceptualized as the permanent eradication of slavery from all United States territory, past, present, and future. It therefore made sense for Lincoln not only to devote the whole of his second inaugural address to the subject of the Civil War, but also to paint the Northern war effort as a crusade of liberation sanctified by God. Even so, there was a curious humility to the speech, because Lincoln remembered something that future generations were far too quick to forget. He recognized that the North had profited from slavery, too, and that it had continued to profit from Southern slavery even as one state after another outlawed the ownership of human beings above the Mason-Dixon Line. Thus he concluded the main body of his address with this whopper of a money shot:

Fondly we do hope and fervently we do pray that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s 250 years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said 3000 years ago, so still it must be said, “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.” |

I don’t believe in God, but I can get behind that sentiment 100%. It’s like a different Abraham said 130 years later: some are guilty, but all are responsible. All free Americans benefited from those centuries of stolen labor, even the staunchest Yankee abolitionist— even the men who were literally fighting and dying to put an end to slavery as Lincoln delivered that speech. And if you’re asking yourself right now what any of this could imaginably have to do with baby-snatching Norwegian doppelgangers, then you’re already on the road to understanding why Jordan Peele’s Us is only about two thirds of a good movie.

It’s 1986, and the Thomas family— father Russell (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II), mother Rayne (Anna Diop), and seven-ish daughter Adelaide (Madison Curry)— are celebrating Russell’s birthday on the Santa Cruz boardwalk and amusement pier. Rayne is a constantly twitching ball of raw nerves, seemingly convinced that the whole place is nothing but one huge concentration of threats to her child’s safety. Eventually, though, even she must stand down and head off in search of a toilet, leaving Adelaide in the sole care of her rather less vigilant dad. Russell becomes engrossed in a game of Whack-a-Mole, and the girl takes advantage of the lapse in his attention to run off onto the beach alone. There, below the level of the boardwalk and in the shadow of the pier, Adelaide finds the pavilion housing the “Vision Quest” mirror maze. Although the attraction is plainly closed for the night, the entrance is unobstructed and the power is on inside. Not really knowing why, Adelaide goes inside— and that’s how she sets herself up for the second-most terrifying experience of her life. There’s another little girl in the mirror maze, you see. Another little girl who looks exactly like her.

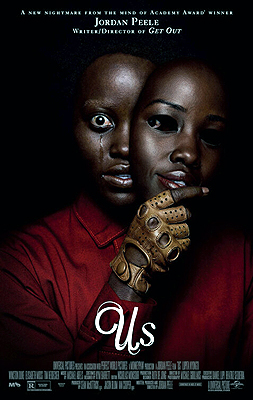

We won’t learn the full story of what happened that night until the end of the film, when Us very calmly and collectedly places its nuts on the dresser, and proceeds to bang on them with a spiked bat. We can say for certain, though, that Adelaide never really got over it, even after 33 years (by which point she’s grown up into Lupita Nyong’o, whom we’ve heard, if not exactly seen, in The Force Awakens and The Last Jedi). Adelaide is married now, to an obviously very successful doer of nerdy things (Engineer? Programmer? Someone who’s gotten full value from a Howard University STEM degree, anyway) by the name of Gabe Wilson (Winston Duke), with whom she has two children: the snide and snarky pre-adolescent Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph) and the younger and much gentler-hearted Jason (Evan Alex). I would love to have seen the conversation wherein it was agreed how the family would spend their vacation this year, because Adelaide is visibly not with the program even as she, Gabe, and the kids unpack the car at their destination. That destination, you see, is Santa Cruz. The Wilsons have joined the family of Gabe’s friend and coworker, Josh Tyler (Tim Heidecker), in renting a pair of luxurious vacation houses backing up to the San Lorenzo River. The houses are a fair distance from the shore, but still too close to the scene of Adelaide’s long-ago fright for her comfort. Naturally it makes her even less comfortable when Gabe announces a day or two later that they and the Tylers are going to the actual, no-fucking-around beach.

Nothing bad happens that afternoon, not really. Adelaide endures hours of dreadfully boring conversation with Josh’s wife, Kitty (Elizabeth Moss, from Midnight Child and The Attic), rubs her remaining patience thin keeping a lid on the petty strife that constantly threatens to break out between Zora and the Tylers’ twin daughters (Cali and Noelle Sheldon), and must pretend to find Josh’s dumb and abrasive sense of humor charming, but there’s certainly no obvious intrusion of the supernatural or whatever. Still, Adelaide keeps seeing things that disquiet her. On the way through the city, the Wilsons pass a group of paramedics loading a badly injured old bum into an ambulance, and she could swear the wounded man is the same homeless Jesus freak that she remembers hanging around the pier that night in 1986. The mirror maze has been renamed and rebranded since then, but looks eerily unchanged just the same. And Adelaide works herself up into quite a scare when Jason runs off to the port-a-johns without telling her, and takes his time moseying back. Still, though, nothing bad actually happens.

The same cannot be said for that evening, however. You remember how I called Adelaide’s childhood meeting with her doppelganger the second-most terrifying experience of her life? Well, the first is about to start. Immediately upon returning to the vacation house, Adelaide tells Gabe that she wants to go home, that she doesn’t feel safe there in Santa Cruz. By way of explanation, she comes clean to him at long last about what she saw in the mirror maze when she was a kid— apparently the first time she’s told that story to anyone in all these years. No sooner does she finish than Jason comes into the room to report that there’s a family standing at the entrance to the driveway. It isn’t the Tylers, either. Backlit as they are by the streetlamps, all that can be seen about the intruders is that they’re an extremely large man, a tall but slender woman, a tweenaged girl, and a somewhat littler boy, but even that is strangely disturbing. Too much like the Wilsons themselves, you know? And as Gabe discovers when he goes outside to respond to the situation in whatever way proves necessary, the resemblances don’t stop there. Indeed, the people in the driveway are distorted but virtually exact doubles not merely of Adelaide, but of Gabe, Zora, and Jason as well. And each of the doubles is armed with a pair of scissors fully big enough, sharp enough, and strong enough to snip off a finger or to serve admirably as a makeshift dirk.

The initial battle is over almost before the Wilsons know it, but the doppelgangers surprisingly leave them mostly unharmed for now. That’s because Mirror Universe Adelaide wants her counterpart to understand what life is like on the other side of the Looking Glass, to recognize before she and her family die that their killers belong to the justified camp. In a voice that sounds as if it hasn’t been used in decades, the duplicate Adelaide recounts a biography that plays like a nightmare inversion of the “real” one’s. She describes an existence devoid of comfort, pleasure, kindness, or even free will. She tells how she paired with Abraham, her ogrish and nearly mindless mate, not because either of them desired it, but because their lives were doomed always to parallel those of Adelaide and Gabe. And she emphasizes, as if there were any question about this, that the children she and Gabe produced were soulless, monstrous copies of Zora and Jason, fit only to murder and destroy. Mirror Universe Adelaide might have lived out her whole allotted span that way, too, were it not for a freak accident that occurred when she was a child— one night when she found her way up from her subterranean realm to discover that there was another world on the surface of the Earth, complete with another her. Ever since, she’s been scheming to return to that world one day, and to take that other girl’s place in the sunlight and fresh air. Somehow, Adelaide’s return to Santa Cruz has given her the chance to do just that, and she’s taking the fullest advantage of the opportunity. In fact, she’s taking even fuller advantage than the present home invasion would imply on its own. You see, the Wilsons aren’t the only family in America with unseen doubles living under the ground in unstinting misery and privation…

In order for me to talk meaningfully about Us— and especially to explain why it ultimately doesn’t work for me— it’ll be necessary to blow its biggest and most important surprises. If you haven’t seen the movie yet, and you want to get the full, dubious value for those surprises, don’t read past the end of the paragraph after this one. What I can do without revealing too much is to praise Us’s first and second acts for their masterful use of foreshadowing, suspense, mystery, and escalation. Of all the longstanding horror premises, the doppelganger without a doubt carries the strongest charge of the uncanny. Barring a narrow range of extreme and unusual circumstances (amnesia, multiple personality disorder, etc.), identity is the one thing we can all be reasonably sure about at all times. You are you and I am me, and nobody else is either one of us. So from the end of the epilogue, when Adelaide does indeed “find herself” in the Vision Quest mirror maze, we know without having to be told a single other thing that something is unfathomably wrong here. (For that matter, kudos to Jordan Peele for the method whereby he introduces the double. We expect to see lots of Adelaides in a mirror maze, but no one can sneak up on their reflection from behind. When Adelaide turns that last corner, and winds up staring point blank at the back of her own head, it takes half a second for your mind to catch up and shout, “Oh fuck— MIRRORS DO NOT WORK LIKE THAT!!!!”) And knowing no more than that something is unfathomably wrong, we’re right there with the adult Adelaide as she frets herself to a frazzle during the family’s outing to the beach. That same horrid uncertainty remains in place even throughout the second Wilson family’s siege on the house and its aftermath, because when Mirror Universe Adelaide explains herself, she does so as if she were relating a fairy tale. Even after she’s finished, we still don’t really understand what these terrible, uncanny creatures are. Then finally, when Us explodes into violence, Peele carefully modulates the intensity in order to let us take in the full implications every time the situation gets worse for the Wilsons, their friends, the city of Santa Cruz, and ultimately the entire United States of America.

I’m immensely impressed, too, with all four of the actors playing the Wilsons and their malign doubles. The key point is that the two halves of each pairing both are and are not the same person, but quite what that means varies from one to another. Gabe and Abraham are like negative images of each other, the latter a dim-witted tower of violent strength, and the former a brainiac who has long fallen out of practice in the use of his considerable brawn. The two little boys, at the opposite extreme, are quite alike in a number of ways. Jason is the least verbal of the surface Wilsons, nearly as silent as the Wilsons from below. Meanwhile, his double (called “Pluto” in the credits, but never named in the film proper) is the least savage of the doppelgangers; we’ll eventually see that Pluto has done far more harm to himself during his short life than he’s ever apparently wanted to do to anyone else. Both boys, furthermore, display a curious, questioning temperament, together with an affinity for mechanical toys (a magic-trick gizmo for Jason, and anything capable of producing flame for the other). In Zora’s case, her sarcasm and inclination to bait her little brother are exaggerated in her double until the casual cruelty of the tween years becomes bloodthirsty viciousness. But because only Adelaide’s duplicate is capable of speech, none of that stuff has any chance to be made explicit. It all has to come across in the performances— and in the physical performances specifically with regard to the doppelgangers. The fact that it actually does leads me to class Shahadi Wright Joseph and Evan Alex with the kids of It and “Stranger Things.” As for Winston Duke, his achievement here is best summed up by the moment in which Gabe goes outside to chase off the intruders. Just contemplate for a bit the acting chops necessary for a black man the size of a Clydesdale to look ludicrously unintimidating while brandishing a baseball bat! Ultimately, however, this is Lupita Nyong’o’s movie, and she dominates it utterly. As we get to know her two characters over the course of the film, it becomes increasingly apparent that the terror which Adelaide has spent her whole life holding at bay was not only mirrored by her double, but provided the impetus for the latter’s eventual attack. And it becomes increasingly apparent, too, that the rage which powers Mirror Universe Adelaide is present just as strongly in the woman upstairs, and is turning her into a force to be reckoned with now that the battle has been joined. With more screen time than her castmates, and dialogue in both of her guises, Nyong’o obviously has the most to work with here, but each Adelaide is a daunting challenge in her own right: terrified yet implacable on one side; an aggrieved victim of barely imaginable horrors, yet a skin-crawling mockery of humanity on the other. To excel in both parts at once is an extraordinary feat.

So how does something so rare and wonderful go so far wrong? The wheels first begin wobbling on their axles when Peele reveals that the Tylers have dopplegangers too. One nightmare shadow-family can be an inexplicable aberration, and the fairy tale language in which Mirror Universe Adelaide couches her introductory spiel encourages us to think in those terms. Add a second family of evil doubles, however, and you don’t have an aberration anymore. At that point, you have a phenomenon, and phenomena require explanations (even if the explanations are magical and irrational). Fortunately, Peele has one at the ready, but unfortunately it’s a sci-fi explanation that sits very uncomfortably beside everything we’ve seen thus far. Also, it makes precious little internal sense, which is a real problem in science fiction. It turns out that They (presumably the same They who faked the Apollo moon landing, killed JFK, and installed chemtrail-dropping equipment on all the world’s commercial aircraft) undertook a massive experiment in mind control at some point. They created subhuman clones of every man, woman, and child in America, hid them in a network of tunnels dug beneath the entire nation, and bound them psychically to their doubles on the surface. “Tethering,” They called it. The idea was that by controlling the behavior of the Tethered, They could control the corresponding people dwelling above ground, but it worked exactly backwards in practice. No matter what instructions, orders, or incentives the Tethered were given, they just compulsively mimed the actions of their human counterparts.

That story suffers from the same defect as pretty much all conspiracy theories, insofar as the more you think about it, the bigger the holes become. Who are They? What is Their objective? Shouldn’t there be about 100,000 easier and more efficient means to Their ends than this preposterous scheme? And if They’ve already got the power to create an entire nation of clones, and to keep anyone from finding out about it for decades at a time, what additional benefit could They possibly gain from even mass mind control? They obviously have functionally infinite resources and influence as it is. Digging further into the practicalities, why has the project been left to chug along all these years even after it was deemed a failure? I mean, the electric bills for the tunnel complex alone must be comparable to the gross national product of Costa Rica! And while Peele went out of his way to provide a food source for the Tethered in the form of millions of rabbits descended from the cloning program’s original lab animals, he neglected to give the rabbits themselves anything to eat or drink. Nor is there any apparent source for the red prison coveralls into which the Tethered all change for their big uprising (they’re all dressed in ordinary street clothes during the flashback sequences) or the identical pairs of scissors which they all use as weapons. And while the real reason behind the scissors is that they’re a reference to the traditional weakness of child-stealing hulders, there’s simply no in-story justification given for them at all. We’ve talked before about how the impossible is far easier to accept than the implausible, and once Us lets us in on what’s really going on, it falls decidedly on the wrong side of that line.

Even then, however, Us isn’t finished undoing itself. Peele has also provided a concluding twist worthy of the latter-day M. Night Shyamalan: Mirror Universe Adelaide is the “real” Adelaide, and the Adelaide we’ve been given to know is the Tethered clone. Tethered Adelaide replaced her human double when they met as children, and it has been her lifelong fear that other girl would one day escape from the catacombs to take her revenge. Here the problem isn’t plausibility, but subtext. It should be obvious by now that we’re meant to read the plight of the Tethered as a metaphor for slavery, both the original chattel variety and the modern descendant practiced under various names within the prison-industrial complex. That’s an awkward fit with the doppelganger trope, but it does at least set up some interesting resonances with the ideas of a nation divided against itself (as in the Civil War) and of ourselves as our own worst enemies (as when we permit injustices to fester until non-violent, non-disruptive solutions become impossible). And if the Tethered are slaves, then their uprising becomes the equivalent of, say, the Haitian Revolution, right? Not so fast. You see, that framing works fine if Tethered Adelaide is the leader, but we learn in the end that she isn’t. What we have here isn’t the oppressed casting off their chains, then, but the personal revenge of a little girl who was stolen by a sci-fi equivalent of the Unseelie Court. And if we insist upon reading it as a tale of liberation anyway, then it becomes the story of a backward and barely-human people who are led to freedom by the civilizing influence of an outsider from the developed West. Now I suppose there may be some value in spinning a White Savior narrative in which the White Savior is black, but I really don’t think that’s what Jordan Peele set out to do here. Because that’s what he did do, we’re left with a brilliantly effective fright film that invites close scrutiny, but then collapses into utter incoherence the moment that scrutiny is applied.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact