Truth or Dare? A Critical Madness (1986) -**

Truth or Dare? A Critical Madness (1986) -**

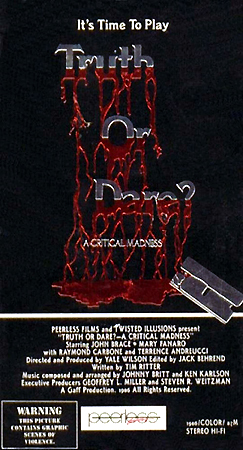

Those of you who are regular B-Fest attendees may have noticed the guy who hands out copies of a new B-movie-themed mix CD every year. Thatís Tim ďCaptain TelstarĒ Lehnerer, who writes Checkpoint Telstar and podcasts on The Fiasco Brothers Watch a Movie, but itís his guise as B-Fest Mix CD Guy that concerns us here. Listeners to Timís 2015 mix were tormented by this recurring synthesizer riffó just 36 seconds of repetitive, low-pitched electronic burbling that popped up again and again. Only the first appearance was credited on the track listing, too (under the title ďTruth or Dare Driving ThemeĒ), so you never knew when it was coming. Every three to six songs, it would just be there: BIR-BIR-BIR-BUR-BUR-BUR-BER-BER BIR-BIR-BIR-BUR-BUR-BUR-BER-BER. It was absolutely fucking maddening. Obviously I had to ask him what in the hell this was about, and thatís how I learned the legend of Truth or Dare? A Critical Madness. A shot-on-video Portrait of a Psychopath movie from an eighteen-year-old Floridian director, Truth or Dare? evaded my notice completely when it crept onto rental shop shelves in 1986, nor did I ever hear of it under my own power in all the years since then. Distribution could be patchy and patternless during the Golden Age of VHS Schlock, though, and up in Wheaton, Illinois, young Mr. Lehnerer stumbled upon Truth or Dare? and fell in love. He and his brothers rented the tape so often that it became a perennial inside joke among them, and when he realized that not even the most expert of his trashfilm-savant friends had ever heard of thing, he felt moved to let us in on the gag. And that brings us back to BIR-BIR-BIR-BUR-BUR-BUR-BER-BER BIR-BIR-BIR-BUR-BUR-BUR-BER-BER. That damnable synth riff has a weirdly specific function in Truth or Dare? A Critical Madness: it plays every time deranged antihero Mike Strauber gets behind the wheel of an automobile. EveryÖ fuckingÖ time. So by scattering it like a field of auditory landmines all over his 2015 B-Fest mix, Tim created a remarkably accurate simulation of what itís like to watch Truth or Dare?. As on the CD, so in the film; itís baffling at first, insufferable later, and ultimately kind of endearing. I wish I could say the same for the movie as a whole, but it never quite reaches Stage 3 there.

Mike Strauber (John Brace) doesnít realize it yet, but his marriage is falling apart. His wife, Sharon (Demon Queenís Mary Farano), is bored out of her mind with her idle lifestyle (Mike is one of those old-fashioned guys who donít want their women to work outside the home, even if there are no kids to look after), and by the time we join the Straubers, sheís starting to weary of Mike himself. Sharon has gone so far as to strike up an affair with Mikeís best friend, Jerry Powers (Bruce Gold), and sheís been at it long enough now to recognize that the illicit relationship is the more satisfying of the two. That said, she still harbors a lot of residual affection for Mike, and she doesnít want to hurt him if she can at all avoid itó especially now, when heís finally getting his life turned back around from that nervous breakdown two years ago. The decision of how to break the news to Mike is taken out of Sharonís hands, however, when her husband comes home unexpectedly one afternoon, and catches her and Jerry in bed together. Mike flees the house at once, and drives off to the beach (BIR-BIR-BIR-BUR-BUR-BUR-BER-BER) to mope, and to make at long last all the connections among half-unnoticed signs and portents from the past several months. He briefly even thinks about killing himself with the revolver he keeps in the glove compartment of his trashwagon Firebird, but soon changes his mind. The crackup Mikeís about to embark on will be much more florid than that.

Time in Truth or Dare? A Critical Madness is slipperier than an oil-wrestling match between hagfish, so I have very little idea how much of it is supposed to elapse between that moment at the beach and the afternoon when Mike stops (BIR-BIR-BIR-BUR-BUR-BUR-BER-BER) to pick up a hitchhiker (Kerry Ellen Walker). At first it seems preposterously accommodating of the girl to drop whatever she was doing and go camping with some sadsack she just met, but her behavior makes sense once it becomes apparent that sheís really just a figment of Mikeís tortured imagination. That night, beside the campfire, Mikeís phantom companion draws him into a game of Truth or Dare, which is a pastime with fraught associations for him. Apparently Mike was so desperate to make friends as a child that heíd let the other kids goad him into extravagant acts of self-harm, and that pattern reasserts itself now. By the time the park ranger inadvertently comes to his rescue, Mike has accepted imaginary dares to amputate his right index finger, to slash open his chest, and to pull out his own tongue.

Mike spends the next thirteen months in the Sunnyville Mental Institution. When he is released, it isnít because his doctors (Rick Paige and Mona Jones) consider him cured, but rather because of the latest round of cuts to the asylumís budget. (That was a real thing that happened in the 80ís, by the way. Tax-averse voters drunk on Reaganomics demanded an end to frivolities like state subsidies for psychiatric hospitals, forcing mass deinstitutionalization as newly cash-strapped mental health facilities prioritized patients who could afford to pay.) The totally predictable result is that Mike makes a beeline for his old house (BIR-BIR-BIR-BUR-BUR-BUR-BER-BER), where he kills Jerry and attempts to kill Sharon as well. Sharon gets in the first slash, though, and the badly wounded Mike is apprehended down the street by police under the leadership of Detective Rosenberg (Killing Spreeís Raymond Carbone).

Back in Sunnyville, Mike manages to find continued opportunities for self-mutilation, despite the not-very-good best efforts of doctors and orderlies alike. Inexplicably, Strauberís therapy includes crafting classes in the hospitalís metal shop (Sure. Give the axe-crazy regular access to welding torches and ball-peen hammersÖ), where he supposedly forges the supposedly copper mask that he wears throughout the rest of the film. He eventually escapes, of course, stealing a getaway car (BIR-BIR-BIR-BUR-BUR-BUR-BER-BER) fortuitously stocked with everything from a chainsaw to a medieval morning star to a Heckler & Koch submachine gun. His killing spree is uncharacteristically random, but Rosenberg correctly figures that Strauber will come gunning for his ex again sooner or later. In addition to Mikeís lead doctor, Rosenberg enlists the aid of a second cop called Pournelle (Terence Andreucci), a hunchbacked bug-eater every bit as incompetent as The Last House on the Leftís Deputy Dumbfuck. Notice that Rosenbergís victory, when it comes, leaves Strauber alive, albeit in custody; incredibly, this movie was followed by three sequels! (Four if you count the one that hasnít been released yet.)

Truth or Dare? A Critical Madness becomes much easier to understand when you realize how young writer/director Tim Ritter was when he made it. If he seems to have little idea how inpatient psychiatric treatment or law enforcement or romantic relationships or basic human psychology work, well, I wasnít too well-versed in most of those things when I was eighteen, either. And to give Ritter credit where itís definitely due, I sure as hell didnít have the discipline at that age to complete a feature film. (You want to know how much of One Fuckiní Stupid Movie we actually shot back when? One scene. One lousy scene. Saint Anthony may know where the tape is now, but I certainly donít.) You must realize, however, that if this is the level of praise Iím granting to Truth or Dare?, it has to be a pretty shitty film. The second and third acts are a dreary Halloween rehash spiced with the most loathsome aspect of The Last House on the Left and an ending lifted from Friday the 13th, Part 2. Furthermore, Ritter makes the fatal mistake of treating his Michael Myers figure as the protagonist. That might seem like it should fly, given how heavily Ritter invests in establishing Mike Strauber as a character during the first half-hour, but I can only assume that among the treatments Mike receives off-camera during his second stay in Sunnyville is a complete personalityectomy. Thereís definitely nothing of any consequence behind that mask once he puts it on. That isnít the only way Truth of Dare?ís opening act fits poorly with what comes after it, either. Mikeís shift from drastic self-harm to murder spree is never really justified, and Ritter finds it increasingly difficult to work Strauberís obsession with Truth or Dare into the Halloween plot template that governs the bulk of the picture. That mismatch is explained, however, by the prehistory of Truth or Dare? A Critical Madness. The year before, Ritter had contributed a segment to a short-film anthology called Twisted Illusions; it concerned a recently divorced man torturing himself to death in a game of Truth or Dare with a pretty hitchhiker who turns out to be an imaginary personification of his own guilt. What worked alright as the climax to a Grand Guignol morality playlet on the EC Comics model is less satisfactory as the origin story for a slasher killer.

All that said, there is a bit of enjoyment to be extracted from Truth or Dare? A Critical Madness if youíre in a sufficiently forgiving mood. Most of it derives from all the different ways in which this movie leaves you blinking at the screen in dull surprise, muttering, ďWhy, though?Ē Iíve already mentioned the enigmatic driving themeó although I havenít yet brought up the magical moment when a chase scene breaks out, and BIR-BIR-BIR-BUR-BUR-BUR-BER-BER unfurls wings I never suspected it had to take flight as a regular musical cue in the ď70ís made-for-TV action movieĒ mold. And I havenít said anything at all about the closing credits song, ďA Critical Madness,Ē which is straight out of a different 70ísó the one that gave us Orcaís ďWe Are OneĒ and Lust for a Vampireís ďStrange Love.Ē Let me tell you, hearing this movieís subtitle warbled over and over again really drives home the point that the phrase doesnít quite manage to mean anything. Also worth a chuckle is the amazing and increasingly improbable array of weapons that Strauber just happens to have on hand whenever he needs them, as if the original owner of the Bonneville he steals from the Sunnyville parking lot picked the Glove Compartment of Holding as a factory option. But in a turn of events virtually without precedent, Truth or Dare?ís most entertaining feature is the Odious Comic Relief. Not that Pournelleís antics are actually funny, you understandó Iíve had more laughs being eaten alive by bedbugs at a motel outside of Youngstown, Ohio. Rather, itís the impression one gets that Terence Andreucci was a wino they caught raiding the craft services table one day, and press-ganged into the cast to work off his lunch. No way in hell do I buy this guy as a cop. And the things Ritter has Pournelle doing! At one point, Pournelle believes that he has Strauber run to ground in a dilapidated shed, which is strangely located in the middle of a fallow field somewhere, unaccompanied by any other sign of human habitation. Rather than attempt an arrest, or call for backup, or anything reasonable like that, Pournelle pours gasoline all over the shed and sets it on fire! In the aftermath, it turns out that the person whom the cop heard shuffling around inside was merely the town drunkó and yet Pournelle is incapable of understanding why Rosenberg thinks this is a problem. Nothing else in Truth or Dare? A Critical Madness suggests a sense of humor half that dark, so it comes as a genuine shock when it happens. Itís probably the movieís only genuine shock, come to think of it.

Every B-Masters Cabal roundtable up to now has been about things that we see. This one is different Itís what we hear, specifically the films whose music made some kind of lasting impression on us. Click the banner below to reach the index to all our contributions. Contrary to all plausible expectations, Iím deliberately not reviewing a punk rock movie.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact