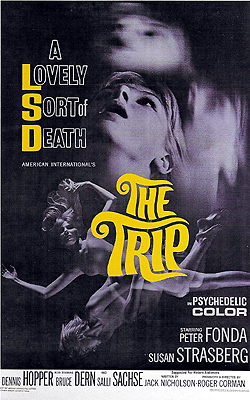

The Trip (1967) ***

The Trip (1967) ***

Lysergic acid diethylamide, commonly known as LSD, was first synthesized by the Swiss chemist Albert Hoffmann in 1938. (That, incidentally, explains why we call it LSD instead of LAD— the German word for “acid” is Säure.) Hoffmann was working for a pharmaceutical company called Sandoz, investigating the toxic fungus ergot as a possible source of new drugs, and it was his hope that LSD might prove useful as an analeptic stimulant. The chemical was basically a bust on that level, but when a very small amount of the stuff (the threshold dosage for producing psychoactive effects in humans is in the range of 20-30 micrograms) soaked through the skin of Hoffmann’s fingertips on April 16th, 1943, he discovered quite by accident that it was extremely potent in an altogether different area. It was a transformative experience for Hoffman, who spent the rest of his career studying not only LSD, but also other hallucinogens from all over the world. In a sense, Hoffman might be looked at as the original acid guru, with his public claims that LSD was “medicine for the soul” vital to the continued evolution of the human race, but up until his death in 2008 at the age of 102, his perspective on the subject was always strictly medical: dropping acid was something one should do only under professional guidance, in a psychoanalytic or psychotherapeutic context. He was not pleased with what became of his pet drug in the 1960’s.

The thing one has to remember in order to make sense of the popularization of LSD during the 60’s is that it was perfectly legal in the United States until October 6th, 1966, while the Sandoz Laboratories patent on it lapsed in 1953. For thirteen years, in other words, any competent organic chemist could make and distribute it provided that they complied with FDA regulations on experimental psychiatric drugs (which were a lot laxer in those days, anyway). When it attracted the attention of people like Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary, and when they began to extol its virtues as a source of insight into at least the inner workings of the mind and quite possibly into the inner workings of the universe, the curious had little difficulty gaining access to LSD in order to see for themselves. There were ongoing clinical trials at universities all over the country, and all one had to do was find one and sign up as a volunteer research subject. Naturally, that meant college students were the most likely demographic for exposure to LSD. Meanwhile, college students were also the most likely demographic for questioning and ultimately rejecting the way their elders were running the world, and for looking to an older generation’s marginalized weirdos— like Aldous Huxley and Timothy Leary, for example— to suggest some possible alternatives. Finally, because the culture against which the youth of the 60’s were beginning to rebel was in many ways defined by its mechanistic and progress-oriented approach to life, it was only natural that the rebellion would include a strong emphasis on mysticism, open irrationality, and magical thinking. LSD was quite simply the right drug at the right time, and unlike cocaine, marijuana, or opiates, it had no stigmatizing cultural baggage attached to it— at least until the proto-hippies themselves added enough to panic the authorities into instituting the ban that has stood ever since. Of course, by then the talking, glow-in-the-dark cat was well out of the bag, and the attitudes toward authority held by anyone who might have considered trying acid in the first place were such that the official interdict could only strengthen their interest in the drug. Anything a corrupt and evil regime wants to keep out of its subjects’ hands has to be good, right?

As in so many things countercultural, California quickly became ground zero for hippydom, and because it was also ground zero for the movie industry, it was only to be expected that the rise of the hippies would mean a concomitant rise of movies both catering to and exploiting them. And given the close association between hippies and recreational and/or entheogenic drug use, it was equally to be expected that the 60’s would see a resurrection of the long-dormant dope-panic movie. The movie industry of the 1960’s was not nearly so thoroughly dominated by huge corporations with much to lose from angering conservative social activists as that of the 1930’s, however. Consequently, the new wave of anti-drug films was counterbalanced to some extent by a concurrent wave of movies (nearly all of them made by relatively young writers and directors working for independent production companies) that showed some sympathy for the counterculture’s take on the issue. Among the most interesting of these, for a variety of reasons, is Roger Corman’s The Trip.

Paul Groves (Peter Fonda, from Spirits of the Dead and Futureworld) directs television commercials for a living; he’s also come to a major crossroads in his life, and doesn’t quite know what to do about it. His marriage, to begin with, is disintegrating, and when we meet his wife, Sally (Susan Strasberg, from Scream of Fear and The Manitou), she’s showing up at a location shoot to remind Paul that he was supposed to have spent the morning meeting with her and her lawyer to sign papers pertaining to their pending divorce. Paul is also professionally dissatisfied, and on a more basic level, he suffers from a vague sense that he’s somehow missing the point of life, the universe, and everything. Paul may be in luck, however, for his friend John (Bruce Dern, of Hush… Hush, Sweet Charlotte and The Cycle Savages) thinks he knows just the thing to help him get to the bottom of his unfulfilled desires. Another of John’s friends, this one called Max (Dennis Hopper, from The Glory Stompers and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2), is a big-time hippy, and Max’s girlfriend, Glenn (Salli Sachse, of Devil’s Angels and The Million Eyes of Sumuru), is a firm believer in the efficacy of LSD as a tool for self-discovery. She takes the stuff all the time, and generally has at least a small supply on hand. If Paul wants, John can bring him over to Max’s place for a Sunshine tablet or two, then hand-hold him through the resulting trip back at his own pad; John might look relatively straitlaced, with his short hair and his tweed suits, but he’s actually had quite a bit of experience with acid. Paul exhibits considerable trepidation in doing so, but he takes John up on the offer.

The rest of the movie— literally the whole rest of the movie— consists of a mostly subjective treatment of Paul’s experiences under the influence of the drug. His chemically assisted soul-searching leads him to confront his ambivalence toward married life generally and toward his marriage to Sally in particular, his fears related to aging and mortality, his subconscious sense of guilt over his involvement with the advertising industry, and his barely articulated longing for transcendence and spiritual meaning. He also manages to sneak away from John while the latter man is out of the room fetching something for his friend to drink, leading to a string of peculiar adventures on the streets of Los Angeles. He inadvertently invades a family’s home, and has a chance to sort of befriend their preteen daughter before Mom and Dad awaken to chase him from the house. He spends some time at a nightclub before fleeing from the two motorcycle cops who stop in— maybe looking for him after his uninvited visit to the strangers’ house, and maybe not. He wanders into a laundromat, where he strikes up a conversation with an understandably rather flummoxed customer (Barboura Morris, from The Wasp Woman and The Haunted Palace). And throughout the night, he keeps having random encounters with an attractive, long-haired blonde (Judy Lang, of Count Yorga, Vampire and The Psycho Lovers), whom he seems to regard as some sort of parallel-life counterpart to Sally. When the trip finally ends the following morning, Paul may not necessarily have the answers he went looking for, but he certainly believes that he has arrived at a clearer understanding of the questions.

The Trip derives most of its appeal and fascination from two intertwined sources. First, it was among the earliest movies to make a serious effort at presenting drug use from the perspective of the user, and second, it was to a great extent autobiographical. Jack Nicholson derived the screenplay from both the collapse of his first marriage and his early experiments with LSD, and he had both Peter Fonda and Bruce Dern drop acid with him before they got to work on the film. Roger Corman, too, did his homework, as it were, and therein, I think, lies the secret to The Trip’s greatest successes. It isn’t just that Corman was working from personal experience in creating the movie’s visual representations of an altered state of consciousness, although that obviously is a significant factor. (In any case, there was only so much that could be done in that direction by raiding the AIP warehouse for its weirdest props, costumes, and set-dressings.) The crucial point, rather, is that Paul Groves might as well be Corman himself, and because Corman was quite possibly the squarest man under 40 in all of Hollywood in the mid-1960’s, when he began coming under the influence of the nascent hippy counterculture, that identification between director and protagonist gives non-hippies an easy in-route to the film. Watching The Trip, I experienced something I never had before— a real sense of attraction toward the most rampantly over-idealized period in recent American history. For the first time in my life, I managed to see past the annoying music, the frequently asinine politics, and the nearly heroic determination to ignore reality in favor of a thousand forms of irrational mumbo-jumbo, to the one seriously cool thing that lay in back of it all. The folks who actually did turn on, tune in, and drop out would surely have done something analogous anyway, and the hippies’ most lasting “achievement” in the political realm was to saddle the Left with so much muzzy-headed bullshit that the delusional malevolence of the Reagan-Falwell axis could later strike most Americans as sensible by comparison. The true accomplishment of the era’s unprecedentedly influential counterculture therefore lay elsewhere, in opening the minds of thoughtful but ordinary people— people like the fictional Paul Groves and the real Roger Corman— to a vast range of new social possibilities. By focusing on someone who isn’t part of the counterculture scene, but who is nevertheless guardedly sympathetic toward it, The Trip gives some indication of how it must have felt to experience that sudden recognition of how broad the horizon really was.

This review is part of the B-Masters Cabal’s month-long look at counterculture exploitation movies. Click the link below to see how my colleagues are faring in their encounters with the various restive youth tribes.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact