Thomasine and Bushrod (1973) **

Thomasine and Bushrod (1973) **

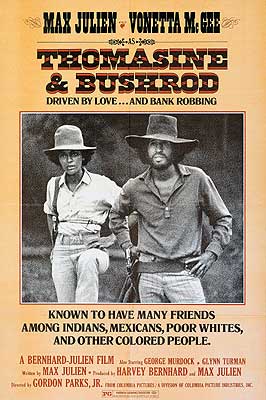

One of the blaxploitation craze’s more significant virtues was that it opened doors to people whose options had been limited so long as the American movie industry catered almost exclusively to the tastes of white audiences. Nor was it just a question of actors getting to be big (or big-ish, anyway) stars when they could formerly have looked forward to careers amounting to one unbroken string of bit-part criminals, bad guy henchmen, and streetwise cellmates. For those who could put a solid hit or two on their resumés, blaxploitation meant a chance to get pet projects onto the desks of producers who never would have given a shit previously, or even to go it alone on the indie circuit. Max Julien, actor and aspiring screenwriter, had exactly that experience when the huge success of The Mack put him briefly in the spotlight. His first attempt to parley stardom into creative license didn’t turn out quite the way he intended, for although Warner Brothers were happy to buy his script for Cleopatra Jones, they had no intention of permitting it to serve its designed purpose as a star-making vehicle for Julien’s girlfriend, Vonetta McGee. (That makes the Warner execs who pushed her out in favor of Tamara Dobson a pack of fools, if you’re asking me, but that’s a subject we’ll take up some other time.) Take two went a bit more satisfactorily. Thomasine and Bushrod found not just a major-studio buyer— Columbia this time— but a major-studio buyer that wouldn’t interfere with Julien’s plans to reserve the lead roles to himself and McGee. Better still, Thomasine and Bushrod would enjoy the services of Gordon Parks Jr., an inexperienced but vastly talented black director, whose Superfly had been even more lucrative than The Mack. Unfortunately, the studio didn’t really know what to do with the completed film, and its theatrical run was both spotty and short-lived. To be honest, though, I can’t entirely blame Columbia’s marketers for their lack of enthusiasm for Thomasine and Bushrod once they had it in their hands. For all its professional fit and finish, this movie is unmistakably a half-baked vanity project. It has the weird tonal shifts, the open defiance of genre expectations, the combination of arthouse sensibility and grindhouse packaging, and a whole bunch of interesting ideas that never properly solidify. It’s a film worth watching more for what it wants to be than for what it is.

Even the setting is odd: Texas in 1911, when the Wild West didn’t yet realize how thoroughly it had been tamed, and when the 20th century was still coasting comfortably along in the groove of the late 19th. A very dangerous woman by the name of Thomasine (McGee, also in Hammer and Blacula) walks into the office of Mr. Bogardie (George Murdock, of Willie Dynamite and Star Trek V: The Final Frontier), the local federal marshal, to collect what she’s owed by him for her latest job. That’s right— Thomasine is a bounty hunter, and a damned good one, too. While waiting for Bogardie to count out her money, she peruses the wanted posters on the marshal’s bulletin board, pulls down a notice advertising a sizable bounty for one J. P. Bushrod (Julien, whose pre-blaxploitation credits include Psych-Out and The Savage Seven), and slips it into her purse.

This Bushrod fellow the law is after is a bit of a drifter, roaming from ranch to ranch breaking horses. He’s at least as good at that as Thomasine is at rounding up felons, but he’s beginning to feel the pinch as first the railroad and now internal combustion engines become increasingly available to do the jobs that formerly required draft animals. It may be that petty theft to make up for lost wages accounts for Bushrod’s wantedness, or it might have something to do with his short temper and ready recourse to violence. None of that matters very much to Thomasine, since she isn’t looking to hunt Bushrod, anyway. Rather, she let herself be seen taking on his case in order to protect him. The two of them used to be lovers years ago, before their solitary temperaments and wandering lifestyles drove them apart, and she’d hate to think of some redneck handing him over to Bogardie— or worse, just shooting him in the back. When Thomasine finds Bushrod to warn him of the price on his head, enough of the old spark remains for her to decide that she wants to stick around for a while. That’s just fine by him, too, as I’m sure any of you who’ve ever seen Vonetta McGee would expect.

The law is not Bushrod’s only enemy, though. Some time ago, his sister was murdered by a gunslinger called Adolf “the Butcher” Smith (Jackson D. Kane, from Boss Nigger and The Man who Fell to Earth), and ever since then, Bushrod has had his eye out for a chance to take revenge. The long-awaited opportunity arises shortly after Thomasine reenters his life, and the resulting gunfight is a remarkably quick and straightforward affair. Unfortunately, Bushrod is not very selective about the venue for the showdown, and within minutes, Bogardie is on the scene with a pistol pointed at his face. That’s when Thomasine does some gunslinging of her own. She doesn’t kill the marshal, but she does throw a big enough scare into him for her and Bushrod to get away. From now on, the couple will be Bogardie’s highest priority, hounded from one end of Texas to the other, and never permitted to settle down long enough to get on each other’s nerves like before.

Mind you, that also means they can never settle down long enough to earn an honest living, so Thomasine and Bushrod take up bank robbery to pay the bills. They fall into their new profession almost by accident, as the result of an encounter with a rich, show-off asshole who happens to have just opened up a bank in one of the little towns they visit. From the look of things, they empty the bastard’s safe just to take him down a peg, but it turns out that robbing banks is something for which they both have a natural talent. Bushrod is accustomed to living simply, though, and a fugitive existence isn’t conducive to amassing property anyway. Consequently, he and Thomasine start playing Robin Hood, giving away all the money they can’t easily carry to the poor and downtrodden— poor and downtrodden blacks, Indians, and Mexicans especially. Before long, the couple are minor folk heroes, and eventually their reputation spreads far beyond their regular stomping grounds. Indeed, it spreads far enough that another old associate of Bushrod’s, a Jamaican outlaw named Jomo Anderson (Glynn Furman, of Gremlins and J. D.’s Revenge), seeks them out to join forces. Thomasine and Bushrod’s main jumping-off point is Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, however, so you can count out anything much resembling a happy ending, no matter how popular the protagonists might be among the oppressed masses.

The Bonnie and Clyde connection is significant, because it helps bring into focus what makes Thomasine and Bushrod so odd, so unsatisfying, and so ill-starred. Max Julien and Gordon Parks Jr. were not out to make “the black Bonnie and Clyde,” or still less “the blaxploitation Bonnie and Clyde.” They just wanted to make a New Hollywood quasi-Western with a premise and style akin to Bonnie and Clyde’s (with a few conspicuous nods to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid along the way). The trouble was, the New Hollywood was just as much a whites-only clubhouse as the old one. Parks and his father were as close as black filmmakers ever came in the 70’s to the kind of recognition enjoyed by Martin Scorcese, Peter Bogdanovich, Robert Altman, and the rest of that lot, and even they got pigeonholed as blaxploitation directors. So while Julien and Parks were able to make the movie they wanted to, Columbia were determined to sell that movie as something else altogether, and therein lies the first of Thomasine and Bushrod’s problems. Most people who see it will come in expecting an action movie rather than a drama. They’ll expect violence and sex instead of somber meditation on the power of class distinctions and gender roles to fuck up people’s lives. They’ll look for jive-talking cool cats sticking it to the man, and be forced instead to settle for an increasingly reluctant criminal who just wanted to provide a simple but secure future for himself and his woman. This movie never stood a chance of being judged on its merits, because the circumstances of its creation artificially imposed a completely different set of standards on it.

I’m going to try to judge it on its merits now, though, even as I recognize that much of my own off-the-cuff reaction was governed by exactly the process I’ve just described. Thomasine and Bushrod is at its best and most interesting when it focuses on the relationship between the two title characters. Although I’m sure Thomasine’s name comes first mainly because that was how Arthur Penn did it, it’s also an accurate reflection of how this couple operates. Throughout the film, Thomasine is the driving force, with Bushrod drifting along in her wake. You can see it even before they start knocking over banks together. Bushrod, in theory, is on the hunt for Adolf the Butcher, but he’s almost entirely passive about his quest for revenge. He just hangs out where he knows the gunman has been before, trusting that he’ll turn up again in one of those places eventually. Thomasine, by contrast, is an active predator during her bounty-hunting days; when that poster in Bogardie’s office inspires her to get in touch with Bushrod, she tracks him to his latest lair and lays him an ambush that would have meant his ass if she were on the clock at the time. Later, it’s her quick thinking that saves Bushrod from Bogardie, since J. P. apparently never planned more than fifteen seconds past the killing shot in his scheme to avenge his sister. And Thomasine is unmistakably the mastermind behind most of their heists. Furthermore, on those rare occasions when Bushrod does think for himself, the outcome is usually something romantic and impractical, like punching a fellow cowboy out for roughing up a bronco unnecessarily or vowing to kill Adolf Smith with no program more detailed than to wait for happenstance to deliver him up. It should go without saying at this point that the whole Robin Hood thing is Bushrod’s trip, too. The dynamics of the relationship run so perfectly contrary to the norms of 1911 that some degree of outlawry was probably inevitable for them— and significantly, it’s exactly when Bushrod starts trying to wear the pants in their household that everything goes to shit. The characterization of Thomasine and Bushrod as gender-role nonconformists is the most fully developed of several themes in which their crime spree mirrors some subtler form of rebellion, painting the outlaws as a sort of two-person counterculture. (Or three-person, after Jomo joins up.)

Unfortunately, Thomasine and Bushrod is a bit too flimsy overall to support that kind of weight. In particular, the vital Robin Hood plot thread isn’t really attached to anything except for Bushrod’s incorrigible romanticism. Thomasine doesn’t resist it like she should, given what we know about her. Jomo doesn’t push to take robbing from the rich and giving to the poor in a more systematic and organized direction, like you would expect of him from the way he seeks out the bandits to become their accomplice. Bogardie never takes the obvious step of infiltrating the communities that benefit from Thomasine and Bushrod’s crimes. Hell, we don’t even get any clear sense of how the robbers’ largesse is improving anyone’s lives. So while Julien, in his capacity as screenwriter, tries to put Thomasine and Bushrod forward as class warriors and agents of racial restitution, it never quite convinces because he and Parks shirk the hard work of actually talking about class and race. They frame everything— even Bogardie’s dogged pursuit of the protagonists— in narrowly personal terms that are inadequate not only for depicting the rise of a band of folk heroes, but even for telling a story about people rejecting that status. It’s all well and good to say that Thomasine and Bushrod shouldn’t be condemned for not comporting itself as the blaxploitation movie it was never intended to be. But this movie is also no more than an interesting misfire when evaluated as the serious social-issues drama that its creators apparently set out to make.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact