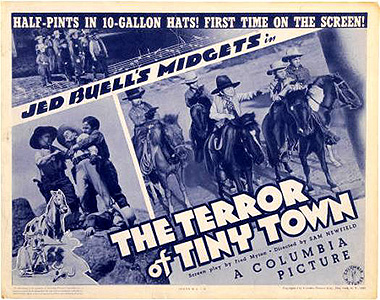

The Terror of Tiny Town (1938) -*½

The Terror of Tiny Town (1938) -*½

We have here what may be the ultimate novelty movie. Seriously, if Spencer Gifts or Archie McFee ever spun off a movie studio, The Terror of Tiny Town is exactly the sort of film they’d make. Plenty of movies have gimmicks, but The Terror of Tiny Town quite simply is its gimmick, and once you get beyond it, there really is no other reason to want to watch the film.

That gimmick, as you may have heard, is a group of actors billed collectively as “Jed Buell’s Midgets,” who comprise the entire cast except for the announcer in an introductory sequence that gets deservedly cut from some prints. I have been able to uncover very little information about Jed Buell, but such data as I possess are tantalizing to say the least. Buell was an independent producer active from about 1936 to about 1942, and his career appears to be roughly divisible into two phases. In the 1930’s, he primarily made no-budget Westerns of the “singing cowboy” persuasion, nearly all of them directed by Poverty Row regular Sam Newfield and starring Fred Scott. His output from the 40’s is more varied in genre terms, and most often saw him partnered with a different Poverty Row luminary, the infamous William Beaudine. But more interesting than the move away from musical Westerns is Buell’s overlapping move into a completely different market segment. Beginning with 1937’s Harlem on the Prairie, Buell devoted a steadily increasing percentage of his efforts to the “race pictures,” Old-Timey Hollywood’s version of Jim Crow. (The race pictures will have to be a topic for another time, I’m afraid. For now, let me limit my comments to expressing an uneasy hope that movies like She Done Him Right and The Bronze Buckaroo did not proudly tout the involvement of “Jed Buell’s Negroes.”) That is a potentially important consideration in assessing The Terror of Tiny Town, for it was shortly after Buell’s first experiment with an all-black cast that he and Newfield tried their hands at an all-midget picture. Were they hoping to launch another parallel cinematic universe along the lines of the race pictures— the height picture, perhaps? Sadly, I have absolutely no idea.

What I do know is that, were it not for the diminutive size of the actors, there would be no significant difference between The Terror of Tiny Town and any of the 40,000 other cheap-shit musical Westerns that came out in 1938. In fact, outside of the aforementioned introduction, the movie never directly acknowledges even that difference, even though none of the performers are in the expected scale to the rented range-town sets. (I like to imagine that one day, a bloodthirsty horde of pillaging midget nomads descended upon what is now Tiny Town, massacring its original, full-sized inhabitants and claiming the land as their own, but that’s just me.) Rancher Pop Lawson (John Bambury) has noticed a marked shortage of calves on part of his land. Suspecting rustlers, he sends his son, Buck (Billy Curtis, from Ghost Catchers and Gorilla at Large), out to investigate. Sure enough, Buck hasn’t been on the afflicted range for five minutes before he spies a bunch of cowboys roping and stealing one of his dad’s calves, and although Buck is unable to run the rustlers to ground, he does find what appears to be their campsite. That campsite holds a significant clue, too, for among the items the cattle thieves left behind is a branding iron bearing the mark of Pop Lawson’s old rival, Jim “Tex” Preston (Bill Platt). Curious then, isn’t it, that Tex Preston is at that very moment receiving a visit from Bat Haynes (Little Billy Rhodes), who is feeding the other rancher a story about how he recently saw Pop Lawson and his men shooting cows on the Preston range. Before the morning is through, Lawson and Preston alike are gunning for each other, and chances are Bat Haynes is the man who stands to gain the most from their incipient feud. That impression is confirmed shortly thereafter, when Haynes drops in on the sheriff (Joseph Herbst), and warns him to stay out of the conflict. You might think that the sheriff, of all people, would be impervious to Bat’s intimidation, but since Haynes is the only one in town who knows that the local lawman is really an escapee from a prison back east, he can be counted upon to do just about anything the black-hat tells him.

Meanwhile, Preston is expecting the arrival of his niece, Nancy (Confessions of an Opium Eater’s Yvonne Moray), on the next stage coach. This is the very same stage that Haynes means to rob (the sheriff has been ordered to keep his nose out of that, too), and his gunmen don’t care overmuch how seriously they endanger any passengers who might be aboard. Luckily, Buck happens to be nearby when the shooting starts, and he both drives off the Haynes gang and brings the stage under control after its two drivers are killed. This, of course, leads to a meeting between him and Nancy, which leads in turn to the two of them falling in love. Singing midget Western Romeo and Juliet in 5, 4, 3, 2...

Unsurprisingly, the sheriff doesn’t exactly spring into action when Buck reports the attack to him. Tex Preston, visiting the sheriff with concerns of his own at about the same time, gets no more satisfactory a response to his demand that men be deputized to guard his ranch, which was recently struck by snipers working for Bat Haynes (but whom Preston has been encouraged to believe were working for Pop Lawson). With the uselessness of the sheriff thus exposed, the stage is set for Preston to hire a private army of mercenary gunslingers, which would naturally push Lawson to take similar action. Buck and Nancy hope at first to talk sense to their respective father figures, but that doesn’t go well. In fact, it isn’t until Buck talks to Preston that any headway gets made in the direction of heading off the big feud that Haynes has so assiduously orchestrated. Unfortunately, Haynes is spying on the men when they have their potentially peacemaking chat, and he shoots Preston down from the cover of a dense patch of shrubbery. Because there were no witnesses to the shooting except for the son of Tex’s greatest enemy, and because everyone at the Preston ranch knew that Tex had gone to meet with Buck alone, Bat is in a perfect position to frame Buck for the crime. Haynes also figures that if Nancy believes Buck killed her uncle, she’ll be open to a new suitor— like Bat Haynes, for instance. And if Nancy won’t play nice, then Bat can always hold all that money Tex owed him (which we’ve never heard one word about until just now) over her head. The trouble with this plan is that Nancy doesn’t like having things held over her head, while Haynes already has a girlfriend in the form of saloon girl Nita (Nita Kress). Nancy’s sharp enough to pick holes in Bat’s story about her uncle’s death once she cools down a little, while Nita is sufficiently vengeful to do just about anything once she catches on that her man is trying to two-time her. Meanwhile, a bid to railroad an innocent man to the gallows might be just the thing to put some backbone into the sheriff’s flaccid conscience.

The most curious thing about The Terror of Tiny Town is that it is almost totally free of what has otherwise been a nearly ubiquitous defect of movies on its level. The acting may stink, the jokes may be corny, the music may be terrible, and the script may not have an original bone in its body, but there isn’t a single plot-hole to be found anywhere in this movie’s 50-odd minutes. I can honestly say that I’ve never seen a film this lousy that was such a marvel of narrative logic and structure. Everything that gets set up pays off; everything that pays off gets set up, with the exception of Tex Preston’s debt to Bat Haynes; nothing in the main plot happens without a motivation that is recognizably applicable to the real world. This is made doubly shocking and perverse by the fact that The Terror of Tiny Town so frequently grinds to a halt for scenes so utterly divorced from that seamless main story that they feel like they were imported from some other movie. Looking over my notes here, I see that literally every other scene description bears the heading, “Pointless Interlude”— a heading under which I include incidents like the nominally comic stalking of Fritzie the duck by Otto the Preston Ranch cook (Charles Becker) and Pop Lawson’s visit to the all-singing, all-sucking barber shop. How is it possible that these purposeless and disruptive vignettes can coexist with the clockwork efficiency of the principal plot? And seriously, what in the hell is up with that penguin in the barber shop?

I didn’t catch on to The Terror of Tiny Town’s case of authorial dissociative identity disorder until I’d seen it a couple of times. What I noticed immediately was that Jed Buell really should have used dwarves instead of midgets. I mean, the freak-show aspect is the sole point of interest in this dire little horse-opera, and from that perspective, short and funny-looking is manifestly superior to just plain short. In practice, the all-midget cast becomes difficult to distinguish from an all-child cast (although there’s certainly nothing childlike about the inhumanly weathered Bill Platt), and Sam Newfield’s direction often actively encourages such perceptual slippage. By about the halfway point, The Terror of Tiny Town starts to feel like a really weird “Little Rascals” vehicle, and there were plenty of times when I found myself wishing ardently for Angelo Rossitto or Billy Barty to correct the focus. Besides, Rossitto would simply have made a much better Bat Haynes than Billy Rhodes, although I suppose he would have found it a challenge to ride even the Shetland ponies that stand in for horses here.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact