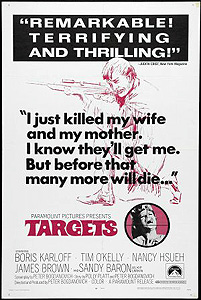

Targets (1968) ***½

Targets (1968) ***½

I didn’t plan it this way, although I should probably just shut up and pretend that I did. Targets got picked for this update for absolutely no better reason than that it was the last movie on a tape that I wanted to put back into circulation, but if there’s a better double-feature companion piece for Fright Night than this movie, I can’t imagine what it might be. On the surface, Targets and Fright Night haven’t a single damn thing in common; one is a deliberately retrograde and slightly campy 1980’s teen horror flick about poofy-haired vampires, while the other is a totally realistic suspense drama about an unhinged sniper, and the directorial debut of perhaps the most Artistically Importanttm graduate ever from the Roger Corman Academy of Film. On a different level, however— one too explicit for subtext, but too metaphorical for text— both are also about the decline into cultural irrelevancy of the horror film as it had been understood from 1931 until the waning years of the 1960’s. Targets is just a little more subtle about it.

Those of you who have seen The Terror (and my condolences to the lot of you) will experience an alarming sort of déjà vu during the opening minutes, for although the main title display unmistakably reads Targets, the rest of the screen is just as unmistakably filled with The Terror’s lethargic conclusion. Do not become alarmed, though. In the Targets universe, The Terror is not the sad, failed Roger Corman Frankenstein experiment that we know, but rather the latest installment in a three-picture collaboration between up-and-coming writer-director Sammy Michaels (writer-director Peter Bogdanovich) and down-and-going actor Byron Orlok (Boris Karloff). The meta-casting is clearly not an accident. Anyway, Michaels, Orlok, and Orlok’s personal secretary, Jenny (Nancy Hsueh)— the latter of whom is also Sammy’s girlfriend— are in a studio screening room, presenting the final cut of The Terror to their bosses, Marshall Smith (Monte Landis, of Body Double and Candy Stripe Nurses) and Ed Loughlin (The Spell’s Arthur Peterson). Neither actor nor director is terribly happy with the film, even if the suits love it, but Michaels has much higher hopes for his next project, a script which he wrote specifically in order to give Orlok something to do outside of the horror genre. That might sound like exciting news for the old star, who has come to feel imprisoned by his track record of playing monsters, killers, and demented barons, but Orlok has already committed himself to quitting the movie business, effective immediately upon the studio’s acceptance of The Terror— ironically enough, he never even read the script that might have changed his mind. Smith and Loughlin are horrified at having no star for the picture on which they’d already agreed to back Michaels, contingent upon Orlok’s participation; Michaels is horrified at the prospect of having the plug pulled on his new movie due to its dismissal by the very person for whom it was written; and Jenny is horrified at the prospect of having to choose between her job (which is going home to Britain as soon as the travel arrangements can be made) and her boyfriend (who is staying right there in Hollywood). Orlok is even fixing to back out of the personal appearance he was slated to make in support of The Terror’s premiere at the Reseda Drive-In’s grand reopening, lawsuits for contract noncompliance be damned!

Meanwhile, elsewhere in Los Angeles, a young man named Bobby Thompson (Tim O’Kelly) has been driving around the city with more guns and ammo in the trunk of his Mustang than some towns’ police departments keep in their central armories. Thompson, as you might well guess upon that basis, is on the verge of a major psychological crackup. Interestingly, we never do learn what’s eating him, but his relationship with his parents— stifling, emasculating mother Charlotte (Mary Jackson, later of Skinned Alive and Exorcist III) and intimidatingly accomplished old-school macho-man father Robert (James Brown, from Space Probe Taurus)— seems to have something to do with it. Maybe it’s as simple as the stress caused by having to live with Mom and Dad still, even though he’s apparently been married for some time. Whatever Bobby’s deal is, he does make one hapless, token effort to talk it out with his wife, Ilene (Tanya Morgan), but his timing totally blows; Ilene is on her way to work when he tries to open up to her, and by the time she comes home, Bobby is as set in his decision as Byron Orlok. Tomorrow, he’s going on a shooting spree, starting with his own family.

Then again, maybe Byron isn’t so inflexible after all. After a maudlin bender in his hotel room with Sammy, Orlok tells Jenny to cancel both his flight to the East Coast and his transoceanic crossing on the Queen Elizabeth II, and places a call to the studio to let them know that he’ll do the premiere in Reseda after all. He still claims he’s retiring, but that’s an argument he and Michaels can reopen another day. What no one has any way of realizing as yet is that Orlok’s reconsideration has put him and his associates on a collision course with Bobby Thompson, for after some predictable police attention drives him from his initial sniping position atop part of a chemical plant overlooking the freeway, he relocates to a perch within the scaffolding supporting the screen at the Reseda Drive-In. The peephole Thompson punches in the screen isn’t big enough to be noticed from the lot, but it affords Bobby a quite adequate means of taking aim at the moviegoers whenever they leave the safety of their cars or turn on their dome lights to facilitate retrieving dropped candy bars.

Okay, so what the hell does any of that have to do with the looming obsolescence of what I like to call the harmless thrill-ride school of horror movies? Well you see, it’s Byron Orlok’s recognition of that very obsolescence that accounts for his determination to retire. In Orlok’s view, the real world has become such a terrifying place that no one has it in them anymore to greet the mad scientists and evil noblemen that he spent the better part of his career playing with much more than a condescending chuckle. What, he essentially asks, is a Dr. Frankenstein beside someone like Charles Joseph Whitman, the University of Texas student who shot 48 people from the top of the administration building at the school’s Austin campus in 1966? Naturally, he gets to find out for himself when Bobby Thompson (an obvious Whitman stand-in) starts taking potshots at the drive-in audience— indeed, Orlok eventually meets Thompson face to face at the movie’s climactic moment. (Targets’ climactic moment, I mean. Not The Terror’s.) It’s that confrontation that makes Targets such an interesting counterpoint to Fright Night, because it creates a sort of yin-and-yang relationship between the two movies. Fright Night, as I’ve said, is a mostly facelift-level update of a thoroughly retro premise, which nevertheless grudgingly accepts that the old movies it pays tribute to really are obsolete. Targets, on the other hand, could scarcely be more modern, coming in with the vanguard of an onslaught of films that blurred the distinction between horror movies and crime thrillers by playing directly to the American public’s escalating fear of crime. Its villain is exactly the sort of person that its own characters agree has superseded any imaginable fantasy bogeyman, and he is portrayed in a way that outstrips even the contemporary Wait Until Dark and The Boston Strangler for unabashedly uncinematic realism. However, when Orlok finally gets a good, close look at Thompson, and sees what a puny, banal, pathetic little man he is, he marvels (as much in regard to his acting career as in regard to the shooting spree he’s just suffered through), “This is what I was so afraid of?” The auto-commentary of Targets thus carries virtually the opposite message to Fright Night’s: larger-than-life evil will always have a role to play in fiction, in whatever medium, because real evil is usually so much smaller than life that the mind refuses to accept it. We cling to monsters because the real-world paradox of sniveling, unmemorable ciphers committing horrifying, unforgettable misdeeds is ultimately irresolvable.

That being the case, never letting us in on what fried Thompson’s circuits is easily the smartest thing Peter Bodganovich does in Targets, because it’s also the most true-to-life. Even when the mass-murderers are a couple of meticulously self-documenting narcissists like Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, we outsiders never really know what finally set them off, or what they thought their outbursts of lethal violence were going to accomplish. At best, we can make a few educated guesses, and that’s all Bogdanovich allows us to do here. There’s no apocalyptic fight with the parents laying out all the participants’ chronically unmet expectations of each other in one neat, orderly array; no career-making promotion that Bobby doesn’t receive; no detectable trace (and this is the most fascinating thing, given that Ilene is Bobby’s first victim) of marital strife or dissatisfaction. Bobby Thompson is as inexplicable as he is unremarkable, and even his own words— in the note he leaves at his parents’ house after the massacre there, in the things he says when the police finally arrive on the scene at the drive-in— offer no clues that we can really use. This is another paradox in action, for although it is completely unsatisfying by the normal standards of drama, it makes Bobby truly frightening, because the vast majority of his victims have nothing at all to do with whatever his problem is. Indeed, for all we know, his family might really have nothing to do with it, either. Having nothing at all to do with the problem means that there is nothing at all that they could have done differently, and thus no way at all that they could have saved themselves. That malevolent randomness plugs Bobby Thompson into the same powerful current of unease that would later fuel Michael Myers in Halloween, despite the vast gulf that otherwise separates the two characters.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact