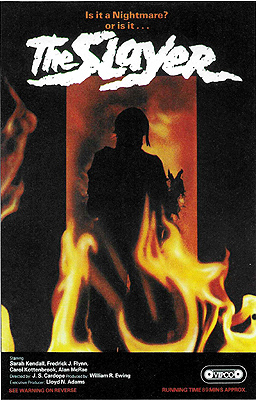

The Slayer (1981) **½

The Slayer (1981) **½

It’s a cliché at this point, but that’s mainly because it’s true— consuming pop culture of any kind frequently is sort of like panning for gold. Panning is a lot of work, and it never gives the prospector a big score in and of itself, but those flecks of gold dust are worth something, and eventually they do add up. Similarly, a committed fan of anything inevitably watches, reads, and listens to a whole lot of shit while searching for the good stuff, and sometimes just a smidgen of that good stuff makes its way into something that’s of little value otherwise. A forgettable novel might feature an unforgettably compelling character. A boring band’s mediocre album might have one unaccountably good song on it. A terrible TV show might manage to shine with unwonted luster on an off-model episode one night. A clunky, poorly made movie might incorporate an idea that deserved a much better airing, or a scene where everything comes together just right in spite of all that goes wrong during the other 87 minutes. The Slayer, as you’ve no doubt surmised by now, is an example of the latter phenomenon. In most respects, it is an unprepossessing and merely adequate slasher film. However, it derives an extra level of interest partly from foregoing the usual cast of supposed teenagers in favor of a small group of similarly isolated and vulnerable adults, and partly from a carefully constructed and slowly escalating ambiguity that eventually leaves it completely in the viewers’ hands to determine which of three drastically divergent stories they just saw.

At the center of the tale are two mid-30’s-ish couples. Kay (Sarah Kendal) is a mentally unbalanced artist who has been plagued all her life by terrifying nightmares, which she has increasingly come to regard as prophetic. Some of Kay’s dreams consist of little more than settings that fill her with ineffable dread; others concern the systematic slaughter of her loved ones by an unstoppable monster. Either way, the dreams have ebbed and flowed in cycles over the course of her life, and right now they’re at high tide again. That’s why Kay’s painting has taken a darkly surrealistic turn of late, ruining her popularity just as her career was beginning to take off. She hopes to gain control over her nightmares by putting them on canvas, but her high emotional pitch and tenuous grasp on rationality suggest that this do-it-yourself psychotherapy isn’t working very well, nevermind what it’s costing her professionally. Kay’s husband, David (Alan McRae, from The Student Body and Once Bitten), is a clinical psychologist; one suspects that anyone without his rigorously honed acumen for dealing with emotional disturbance would have fled the relationship a long time ago. David’s brother, Eric (Frederick Flynn, of Shadowzone and Shadowhunter), rather wishes he would do just that. The familiarity with which Eric treats Kay might be taken to imply that they were friends first, and that Eric introduced her to her husband, but whatever closeness they once shared is clearly badly frayed now. Eric is wedded as well, but Brooke (Carol Kottenbrook, from Cycle Vixens and Survival Quest) is the least developed of the four major characters, and it’s hard to get a fix on either the second couple’s marriage or Brooke’s relationship with Kay and David.

In any case, the foursome are all en route to a vacation at the giant beach house just bought by a mutual friend whom we’ll never actually meet. The place stands on a tiny, low-lying island off the Georgia coast, which it shares with a very few other residences. Ruins elsewhere on the island indicate that it was a resort of some consequence in the fairly recent past, but it seems that the only people still clinging to it today are a handful of fishermen too set in their ways to consider living anywhere else. Most likely that change can be blamed on the island’s vulnerability to hurricanes; as Marsh (Outside Ozona’s Michael Holmes), the pilot transporting the two couples, warns on the flight in, two such storms are bearing down on it even now. Marsh’s plane is too small and fragile to stand up to that kind of weather out in the open, so he’ll have to split as soon as he drops off his passengers. And once the storms hit, Kay, David, Eric, and Brooke will be completely cut off until they subside.

A funny thing about this island, though… Kay knows it like the back of her hand, even though she’s never set foot there in her life, nor indeed had any reason to. The steroidal beach cottage, the boathouse, the pier, the derelict theater on the lee side of the dunes, the tangle of woods at the center of the island— Kay has seen every one of them in her dreams, and has even painted a few of them. Her husband and friends unanimously insist that there’s nothing but weird coincidence at work, but we all know better than that, right? Sure enough, no sooner are the vacationers ensconced in the house than somebody creeps up on one of those stubborn old anglers I mentioned, and beats him to death with an oar. The killer comes calling at the beach house next, claiming a single victim on each of the next three hurricane-wracked nights, but there’s more at issue here than the usual “who’s doing it?” Eric believes that Marsh is the murderer, that instead of leaving the island like he said he was going to, he found some manner of shelter for his plane and stuck around to thrill-kill his customers. Kay, however, reminds her surviving companions that she has dreamed these very events, or variations thereupon, any number of times. She thinks her subconscious has literally created a monster, and that the worsening of her nightmares corresponds to the waxing of that monster’s power over the real world. Can it really be a coincidence, she asks, that the murders occur only while she sleeps, in exact duplication of the dreams she has while they happen? But there’s another possibility, too— albeit one that none of the characters ever raises directly. Might it be that Kay herself is the murderer, killing in a somnambulistic trance and building dreams around her crimes as a defense mechanism against her own guilt?

The impressive thing about The Slayer is that it builds more than a fair case for each of those interpretations, and ends on a note that forecloses none of them. Marsh really is on the island during the climactic events, and might indeed have been there all along. Kay eventually comes face to face with the creature of her nightmares, but on terms fully compatible with the confrontation being all in her head— and besides, what would a monster need with an oar or a pitchfork, anyway? Most importantly, Kay unmistakably is mad at the last, and has entirely sufficient reason to harbor vengeful feelings of resentment for all the belittlement and persecution she habitually receives from her friends. Even the momentarily annoying “all just a dream” coda feeds into the central enigma, because it makes clear that the main body of the film was not merely a dream, but the dream— that is, the original iteration of the nightmare which the adult Kay believes to foretell the doom of everyone she cares about. Knowing that she really does see it all coming tells us nothing about what “it” really is, and leaves us commendably no closer to certainty about whether Marsh or Kay or a projection of Kay’s tortured subconscious is destined to become the agent of all the impending bloodshed. Rarely have I seen a slasher movie attempt anything half this ambitious, let alone a slasher movie that never received more than regional distribution and therefore went virtually unseen by anybody. (The Slayer’s extreme lack of success in securing bookings outside of writer/director J. S. Cardone’s home turf is the one thing stopping me from suggesting this movie as an unheralded influence on A Nightmare on Elm Street.) I learned a long time ago not to ask very much of films in this subgenre, so seeing one try this hard to do something truly different, this early into the initial efflorescence of the form, is a most welcome surprise, earning The Slayer my forgiveness for a host of the usual minor sins.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact