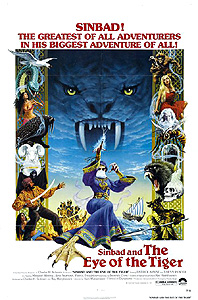

Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977) **½

Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger (1977) **½

Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger, the last of the Harryhausen Sinbad movies produced by Charles Schneer for Columbia Pictures, has developed a most unenviable reputation in the years since its release. It’s perfectly easy to understand why. Of the three films in the series, Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger features the drabbest and most forgettable actor in the role of Sinbad, along with the dullest and least colorful villain. Not only that, it also seems to have been hit hardest by the runaway inflation of the 1970’s. As with the later Clash of the Titans, Harryhausen’s monsters are a notably uneven lot in this movie, some of the stop-motion wizard’s better creations sharing the screen with one of his worst. And again like Clash of the Titans, it appears that the shabbier creatures got that way because of the shrinking buying power of a fixed budget over the course of the film’s typically lengthy shooting cycle. Nevertheless, I slightly prefer Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger to the preceding The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, largely because it possesses a tauter story and an unusually capable supporting cast, while offering the female lead a few unexpected opportunities to do something other than stand on the sidelines looking pretty.

Continuing the tradition established by the previous installments, Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger begins by immediately revealing the existence of some kind of magical malfeasance that requires a hero to put it right. A kingdom somewhere in the Arab world is about to crown its prince, Kassim (Damien Thomas, from Twins of Evil), caliph, but something goes disastrously wrong at the coronation ceremony. Fortunately, Sinbad the sailor (played this time by John Wayne’s son, Patrick, who was also in Beyond Atlantis and The People that Time Forgot at about the same time) is even then on his way to the kingdom, for he is a close personal friend of Prince Kassim, and a longtime lover of his sister, Farah (Jane Seymour, from “Battlestar Galactica” and Frankenstein: The True Story). Sinbad and his men find Kassim’s capital city under curfew when they arrive, and are told that the town is plague-ridden. The man who offers this information, a merchant named Rafi (Kurt Christian, playing a different character than he had in The Golden Voyage of Sinbad), also extends to Sinbad the hospitality of his tent, and the captain and his landing party accept Rafi’s generosity. This is a mistake on their parts, however, for Rafi is no merchant. In fact, he is the son of Queen Zenobia (Margaret Whitting) and the stepbrother of Prince Kassim, and it is his mother who is behind all the mystical mischief. The wine Rafi serves to Sinbad and his men is poisoned, but the drug is so fast-acting that one of the sailors tips the others off by dying before they’ve had a chance to sample their own drinks. That’s when Zenobia herself appears in the tent, and raises a trio of demons to finish the job. The creatures cannot be harmed by the sailors’ scimitars, and Sinbad’s men are forced to flee to their ship. Along the way (and after dealing with the pursuing demons by means of a cargo pallet laden with logs), they meet up with Princess Farah, who snuck out beyond the city wall when she saw Sinbad’s ship arrive at the docks. It is Farah who tells the captain that Zenobia has bewitched her brother in order to prevent his assumption of the throne. Because local custom dictates that an heir has but seven months to claim the caliphate, and forbids women to reign in their own right, the crown will devolve to Rafi if the spell on Kassim is not broken.

So just what is this enchantment that prevents Prince Kassim from ascending to the throne? Zenobia has turned her stepson into a baboon! Kassim still retains most of his human mental faculties (he’s a fiendishly competent chess player, for instance), but that doesn’t appear to matter for inheritance purposes. His uncle, the grand vizier (Bruno Barnabe, of The Mummy’s Shroud), has consulted all the greatest sages and wise men in the realm, and not a one of them has the necessary know-how to reverse the transformation. The vizier and the princess are now staking their hopes on the chance that a world-traveler like Sinbad might know of a more powerful magician in another land. As a matter of fact, Sinbad does. On a remote island in the Mediterranean, it is said that there lives an immensely powerful wizard named Melanthius. It may well be that Melanthius no longer lives, or even that he never existed in the first place, but all concerned are in agreement that a voyage to his island retreat is the only chance of restoring Kassim to his natural form.

You can imagine how much Zenobia likes that idea. Realizing that Sinbad is just the man to carry off this hazardous mission, Zenobia sets out to follow him and get in his way. To this end, she builds herself a small, swift, bronze-hulled galley, and to pilot it, a living bronze minotaur which she rather unimaginatively names Minoton. Zenobia stays hot on Sinbad’s heels until her ship tears up its oars on the rocks that surround the island where Melanthius is supposed to dwell. By the time Rafi gets them fixed (one assumes Minoton, although more than strong enough, is too clumsy for the job), Sinbad and company have already found Melanthius (Patrick Troughton, from Jason and the Argonauts and The Omen), and talked him and his daughter, Dionae (The Sea Serpent’s Taryn Power), into helping Kassim. To do so will require another long and perilous voyage, of course. The only power sufficient to overcome Zenobia’s spell belongs to an ancient and extinct civilization, based in the temperate valley of Hyperborea, hidden among the frozen wastes of the far North. The Anamaspai of Hyperborea were far more advanced than any people left on Earth today, and had entirely mastered the art of transmuting matter. In the Anamaspai Shrine of the Four Elements, there is a machine that should be able to de-monkeyfy Kassim quite easily.

The next part of this movie bears a suspicious resemblance to the last one, as Zenobia sticks close behind Sinbad, using sorcerous means to figure out where he’s going and to prevent or at least delay him getting there. Like Koura in The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, she gets what she wants, but at considerable personal cost, and she is able to reach Hyperborea right about when her opponents do. This would seem to put the advantage still with her— she’s got Minoton, after all— but Sinbad’s company evens the odds when they befriend a hulking Troglodyte, who accompanies them on their trek to the shrine, apparently because he thinks Farah is cute. (Makes sense, I suppose— she is.) Nevertheless, there’s one thing neither party has reckoned on: the Shrine of the Four Elements has not been left unattended all these eons. It may be encased in a block of ice at the moment, but that giant sabretooth tiger is sure to cause lots of trouble if it should happen to thaw out.

Okay— here’s my question: Why in the hell is this movie called Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger? Granted, there’s that frozen Smilodon in the shrine, and Zenobia gets these weird, green cat-eyes whenever she casts a spell, but neither one of those things would seem to be significant enough to the story to merit deriving the title from them. The movie’s working title, Sinbad at the World’s End, would have made much more sense, although I suppose it’s not quite as snappy as the one ultimately adopted. That little bit of authorial laziness is somewhat surprising, because Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger really has the most coherent script of the series. The dialogue is just as lousy as it is in everything else Beverley Cross wrote, to be sure, but this movie has none of the gaping plot holes which formed the other signature feature of the writing in Columbia’s fantasy adventure films. (Remember the orphaned plot thread regarding Margiana’s mystical link to Sinbad in The Golden Voyage of Sinbad? What about the ending of Jason and the Argonauts, which completely ignores the entire point of the story?) Apart from a couple of randomly placed monster set-pieces (the one with the giant walrus, for instance), there’s nothing in this screenplay that doesn’t belong there, nor is anything really necessary absent from it.

No, this time the primary fault lies with the two central characters, Patrick Wayne’s Sinbad and Margaret Whitting’s Zenobia. With his athletic build, swarthy complexion, and plausibly Levantine beard, Wayne at least looks the part, but then he goes and blows everything by opening up his mouth. I suppose we can say that makes the match-up between him and Whitting a fair one, for rarely have I seen a less intimidating evil magician. There’s nothing like her performance to make you appreciate Torrin Thatcher’s mostly risible turn as Sokurah in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad; if you can’t do dignified malice (a la Tom Baker in the previous movie), you should at least strive for diabolical flamboyance! Faking an accent and scowling is not enough. What saves the movie from the two feeble antagonists is a strong supporting cast, at least by the standards of a Harryhausen fantasy flick. She may not have the eye-candy value of Caroline Munro (and let’s face it— not many women do), but Jane Seymour makes the most of what limited opportunities for real acting the screenplay allows her. After all, she’s playing a woman whose brother has been turned into a fucking ape. You’d expect a certain amount of anguished histrionics from her, and Seymour delivers without taking it too far. More important still is Patrick Troughton’s performance. His Melanthius is believably eccentric, and Troughton is absolutely the only member of the cast who never seems like he’s about to choke on the crummy dialogue Cross wrote for him.

“Yeah, yeah, yeah,” you say. “So what? Tell us about the monsters.” Hey— I was getting to that. Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger is a mixed bag on that front. None of the creatures in this outing are as imaginative as the standouts from earlier Harryhausen films, but the best of them are among his most accomplished, technically speaking. Monkey-Kassim and the giant walrus in particular are excellent. They almost look like the real thing. The Troglodyte is another quality critter; together with Kassim, he’s one of the most expressive creatures Harryhausen has ever come up with. The demons that attack Sinbad’s men in Rafi’s tent are interesting, but it’s also obvious that they were written in as an attempt to recapture the magic of the skeleton swordsmen from Jason and the Argonauts, and it doesn’t quite pan out. The only real failure, unfortunately, is one of the more important monsters. The sabertooth guarding the Shrine of the Four Elements is simply awful. Its proportions aren’t even remotely cat-like, and it looks to have been cobbled together from scraps using whatever money was left over after everything else— including the extras and the caterer— had been paid for. The worst thing about it are its eyes, which couldn’t possibly be mistaken for anything other than colored glass. And as if somebody wanted to make absolutely certain that everyone in the audience was fully aware of what a lackluster job the giant cat was, it spends most of its big scene wrestling with the magnificent Troglodyte. Nevertheless, Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger is a decent enough stop-motion monster fest, and one of the last members of what is now a long-dead breed.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact