Sheba, Baby (1975) **

Sheba, Baby (1975) **

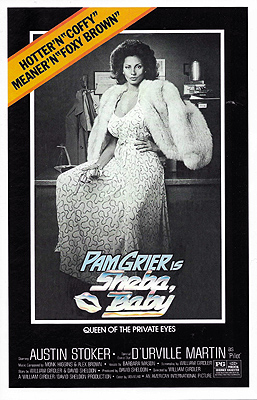

Few American actresses have ever kicked ass as reliably as Pam Grier in her blaxploitation heyday. I don’t think anybody would seriously dispute that. At the same time, though, I don’t think it’s open to serious dispute, either, that too many of Grier’s projects during that era simply weren’t worthy of her. Vexingly, that applies not only to her earliest appearances, playing supporting parts in movies whose directors could be excused for failing to appreciate what they had in her, but even to some of the films purpose-designed as Pam Grier star vehicles. Consider Sheba, Baby as an example. This picture, Grier’s last as an American International contract player, was supposed to carry on the legacy of Coffy and Foxy Brown, but it’s disappointingly limp on the action front, and offers not nearly enough of writer/director William Girdler’s usual zany strangeness to compensate.

Louisville, Kentucky— Girdler’s home turf. A crime lord known only as Pilot (D’Urville Martin, from The Legend of Nigger Charley and Hammer) has been forging all the independent businesses in the city’s black neighborhoods into a sprawling commercial empire by strong-arming their owners into selling out to him or his agents. He started with the pawn shops, moved on to the used car dealerships, and now has his sights set on the Shayne Loan Company, one of the few financial institutions in town that will lend money to black borrowers on remotely equitable terms. Presumably Pilot figures on turning the operation over to his loan shark underling, Walker (Christopher Joy, of Darktown Strutters and Cleopatra Jones), once he has it in his hands. Owner Andy Shayne (Rudy Challenger, from Detroit 9000 and Hit Man) is determined to hold out against the pressure, however, heedless of blandishments and threats alike. Not even Andy’s risk-averse right-hand man, Brick Williams (Austin Stoker, of Assault on Precinct 13 and Time Walker), can convince him that this might be one of those times when discretion is the better part of valor, and thus it is that the stubborn old man buys himself a beating from a posse of Pilot’s goons.

Brick probably thinks he’s enlisting a second voice in favor of caution and conciliation when he wires Andy’s daughter, Sheba (Grier, whom we’ve seen before in The Big Doll House, and will see again one of these days in Friday Foster), in Chicago with news of Shayne’s troubles. You know what they say, though, about the falling radius of acorns. Sheba is, if anything, even steelier than her dad, and as an ex-cop turned private eye, she has the training and experience with armed violence that Andy and Brick both lack. When Pilot turns up the heat on Shayne to life-threatening levels, he can count on getting the same right back from Sheba. Indeed, even the gangster himself figures out pretty quickly that he’s cooking his own goose, and orders his lieutenants to calibrate their intimidation tactics very carefully going forward. Alas, criminals are justly not famous for their impulse control, and the next bunch of leg-breakers who drop in on the Shayne offices get into a shootout with Sheba that not only leaves all but one of them dead, but puts Andy in the hospital in critical condition as well. Pilot had a fight on his hands to start with, but now he’s got a war.

Pilot does have one advantage, however, in that he’s always been careful to ensure that none of his targets ever learned exactly whom they were up against. He might make a phone call to a prospective seller himself, but all face-to-face interactions occur through go-betweens of one sort or another. Consequently, neither Andy nor Brick has been able to tell Sheba so much as the name of the man trying to steal the family business out from under them, and the one lead that Williams has managed to turn up— all the black entrepreneurs targeted by criminals lately employed the same insurance firm— looks at first like misdirection, since there’s no indication otherwise that Pilot has any interest in insurance beyond maybe a protection racket. Remember, though: Sheba’s a detective. Pilot’s amateur-night efforts at secrecy aren’t going to hold up for long, and although Williams doesn’t realize it yet, he’s actually spotted the trail of the much bigger fish (Richard Merrifield, of The Hellcats and The Sidehackers) directing Pilot’s activities from yet further below the surface.

I expected both more and less from William Girdler. Sheba, Baby is a tad more technically competent than most of his better-remembered films, but only a tad. And the price for seeing Girdler more or less behave himself is having to watch him more or less behave himself. I mean, let’s face it: nobody wants to see a passable, by-the-numbers crime flick from the director of Abby and Asylum of Satan. The world is full of filmmakers who do that far more effectively than Girdler ever could. Even on his best behavior, Girdler was still the kind of screenwriter who, having teased the existence of a crooked insurer pulling the hands-on villain’s strings, never directly mentions that again, and leaves it to us to connect the dots between scammy insurance and the white gangster whose yacht becomes the main venue for the final act. He was still the kind of writer who jumps the gun on the expected scene in which Pilot throws a temper tantrum over Sheba’s intervention in front of all his minions, inserting it at a point in the narrative when she’s crossed his path only once, and hasn’t yet caused him worse than a trivial inconvenience. And he was still the kind of director who persuades his leading lady to take part in an insanely dangerous automotive stunt, but then mounts it with such a lack of fanfare that the viewer realizes only in retrospect what a set of brass balls she had to strap on in order to do it.

No, we who knowingly watch William Girdler movies do so because we want (to cite just one not-at-all-made-up example) to see Leslie Nielsen strip off his shirt to wrestle a grizzly bear in a thunderstorm while bellowing about believing in “Melville’s God.” Sheba, Baby, sadly, offers very little in that direction— and some of what it does offer becomes apparent only during the closing credits, since it’s impossible to tell that seven eighths of the baddies have inexplicably nautical or ichthyological names if nobody ever says them aloud. Still, there aren’t many climactic shootouts in blaxploitation that arm one of the participants with a spear gun, so kudos for that. Also, I have to applaud Sheba’s creativity in the field of enhanced interrogation techniques, like when she repeatedly dunks one hood face-first into a barrel of swimming pool chlorine powder, or when she shoves Walker out the driver’s-side window of his Lincoln while it’s going through an automated carwash. (“Do I need to remind you that you ordered hot wax?” she snarls.) And since one of Girdler’s most noticeable recurring quirks was his staggeringly bad taste in practically everything, I suppose Sheba, Baby deserves a shout-out for being one of the few films that ever managed to find clothes that look bad on Pam Grier. None of that suffices, though, to keep this movie from feeling anything more than tired and junky.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact