The Shape of Water (2017) **½

The Shape of Water (2017) **½

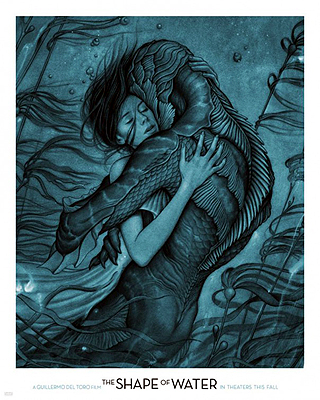

Guillermo del Toro was seven years old the first time he saw The Creature from the Black Lagoon, so in a sense, The Shape of Water has been in development for a very long time. The seed of its existence was planted when del Toro first beheld that unforgettable, beautiful scene in which Kay Lawrence goes for a swim in the Black Lagoon, unaware that the gill-man is mirroring her every move below the water, as if they were the leads in an Esther Williams routine about interspecies rape. That wasn’t how the young del Toro interpreted the scene, however. Identifying, as always, with the monster, and exhibiting a young child’s typical indifference toward the practicalities of love and sex, he thought Kay and the gill-man made a cute couple. He thought they should totally hook up. And now, 46 years later, he’s given us a movie in which they do.

Elisa Esposito (Sally Hawkins, from Godzilla and The Killing Gene) lives in a version of early-60’s Baltimore nearly as convincing as the New York City of Rumble in the Bronx. Orphaned and mute since infancy thanks to a mysterious injury that left her with perfectly symmetrical trios of evenly-spaced scars on either side of her neck, Elisa has always had to make her own family, and her disability has naturally predisposed her to seek the company of others who don’t quite fit into the rigidly conformist society of mid-20th-century America. She rents an apartment above the movie theater owned by an Armenian immigrant named Arouzmanian (Shallow Ground’s John Kapelos)— remember that Armenia was part of the Soviet Union at the time— and her two best friends are her gay, alcoholic next-door neighbor, Giles (Richard Jenkins, from Kong: Skull Island and The Broken), and a black lady named Zelda (Octavia Spencer, of Snowpiercer and Halloween II) who has made an art form of staying positive despite a shitty marriage. The life Elisa has built for herself seems to suit her, even if its routine is so invariable that she actually uses an egg-timer to govern her daily bathtime masturbation sessions.

It appears that Zelda is to thank for Elisa’s new job on the cleaning staff at Occam Aerospace, an outpost of the military-industrial complex on the outskirts of the city. She’s been working there only a few days before something she sees by accident sucks her into an affair that will eventually blow her comfortable routine wide open. One of the labs in Occam’s basement contains a setup that doesn’t look at all aerospacy, but neither Elisa nor Zelda initially questions what aircraft developers might need with a huge tank of warm, brackish water. Then their Ned Flanders-ish boss, Mr. Fleming (David Hewlett, of Pin and Scanners II: The New Order) introduces them to the men who will have shared control over that lab: Dr. Robert Hoffstetler (Michael Stuhlbarg, from Men in Black 3 and Arrival) and Richard Strickland (Michael Shannon, of Dead Birds and Bug), Occam’s chief of security. The reason why neither woman had met them before is because they’ve been down in South America for six months or so, capturing the amphibious, humanoid creature (Doug Jones, who’s been playing monsters for del Toro ever since Mimic) that will henceforth be living in that tank. That’s rather a drastic step down for the organism, incidentally; back home, the local Indios worshipped it as a god. Probably Elisa and Zelda aren’t even supposed to see the gill-man, but women of their station are so invisible to men like Strickland that I’m sure he never gives it a moment’s thought until Elisa gives him specific reason to.

She does that by making friends with the thing in the tank, and under circumstances guaranteed to annoy the security chief, at that. One day, Elisa and Zelda are called to the basement lab on an emergency basis to mop up an astonishing amount of blood. Most of it clearly belongs to Strickland, whom the cleaners pass in the corridor being rushed to the infirmary with a mangled hand. (Elisa later finds two of his fingers on the laboratory floor, and thoughtfully saves them for possible reattachment.) But some must also have come from the gill-man, which Strickland takes visible delight in torturing. Knowing full well that most animals take a “don’t start none, won’t be none” attitude toward interactions with human beings, Elisa quickly and correctly assesses where the fault lay with this latest altercation. She sneaks back down to the lab on her lunch break, and offers the gill-man a hard-boiled egg. She also shows it the gesture that means “egg” in American Sign Language, reinforcing the concept each time she proffers the snack. In the weeks and months to come, Elisa spends just about all her lunch hours with the gill-man, giving it various sorts of treats, teaching it the rudiments of ASL, and cultivating in it an appreciation for big band music with the aid of a portable record player. Elisa believes that she does all this unobserved, but that’s not quite correct. Sometimes she’s watched surreptitiously by Dr. Hoffstetler, who is astounded and inspired by what he sees.

Now you might ask what the lead scientist on the gill-man project is doing skulking around his own lab like a common industrial saboteur. In point of fact, Hoffstetler is something even worse than that— he’s an agent for the KGB. His mission is partly to learn whatever he can about the creature (which both Cold War adversaries rather absurdly imagine to have much to teach their respective space programs about survival in environments inhospitable to humans), and partly to prevent the Americans from learning anything useful about it. The scientist-agent must therefore succeed in his research while appearing to fail spectacularly. That was a tall order even before Elisa inadvertently revealed to Hoffstetler just how much there was to be learned about the creature, let alone before she made it impossible for him to see it as merely an animal. The new perspective opened up by the cleaning lady’s befriending of the gill-man puts Hoffstetler in a real bind. Occam’s military liaison, General Hoyt (Nick Searcy), is growing impatient with the lack of progress, and that impatience is making him ever more receptive to Strickland’s advice that the only productive way to study the creature is to vivisect it. The high-ranking spy to whom Hoffstetler reports (Nigel Bennett) is adamant, meanwhile, that any vivisection attempt must be preempted by poisoning the creature at once. That means Hoffstetler’s only true ally when it comes to the gill-man is Elisa, who unbeknownst to him began plotting to smuggle the creature out of the lab the moment she first heard Strickland mention vivisection. In effect, Elisa solves the scientist’s problem for him by moving to spring the gill-man on the very night when Hoffstetler receives his orders to kill it— and the measures Hoffstetler was to take to cover his own actions end up covering Elisa’s just as well.

There’s still one rather serious problem facing Elisa and her ad-hoc People for the Ethical Treatment of Gill-Men club, however. Obviously the creature will have to return home in order to be permanently safe, but the only access to the sea from Elisa’s neighborhood is a canal that won’t fill sufficiently until the autumn rains get well underway. (In the real world, Baltimore has no canals, nor has it ever. If I were trying to sneak a gill-man out of the city, I’d dump it into the Jones Falls, right where they disappear into the man-made tunnels under the Jones Falls Expressway. Early November really would be the best time to do it, however, and Baltimore’s combination of soggy autumns and bone-dry summers really is the reason why.) Throughout the time it takes for the water level in the canal to rise, the gill-man bivouacs in the tub in the bathroom serving Elisa’s and Giles’s apartments, an arrangement which gives Elisa the chance to decide that she likes the thing even more than she realized. As in, likes enough to start wondering how a cloaca works. But while those two are turning the Black Lagoon Blue, General Hoyt informs Strickland in no uncertain terms that his future depends upon the creature’s recapture, and Hoffstetler’s superiors at the KGB begin poking holes in his story about what happened on the night when he was supposed to poison it. Elisa, Giles, and Zelda simply aren’t qualified to put one over on that many professional spooks, and Hoffstetler is rapidly approaching the end of his ability to assist them.

I’ll start with the good news. The Shape of Water is a technically impeccable film. Cinematography, editing, production design, the costume for the gill-man itself— all that stuff is completely up to Guillermo del Toro’s highest standard. The cast are everything one could ask for, and they all make this shit look easy while they’re at it. I even suspect that viewers who don’t know from personal experience what Baltimore is supposed to look like will find the setting as immersive as Crimson Peak’s Allerdale Hall or the alternate history Hong Kong of Pacific Rim. Del Toro’s personal investment in and commitment to this labor of half a century’s love shines through every second, enabling him to pull off a number of what would normally seem to be highly dubious choices. My God, the black-and-white dream sequence in which Elisa and the gill-man become Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire more or less works! (And a big “HOLY SHIT!” to Doug Jones for dancing like that in a fucking monster suit.) One doesn’t often see a film that unmistakably is exactly the movie its creators set out to make, and if nothing else, The Shape of Water is that.

So how, then, does The Shape of Water also wind up being del Toro’s weakest work since Hellboy, wildly unlikely “Best Picture” Oscar notwithstanding? Like the film itself, the central problem goes back to that seven-year-old boy watching The Creature from the Black Lagoon. Children at that age don’t grasp that sexual love is different from the love they might feel for their siblings, parents, pets, or favorite toys. It’s why so many little girls, for example, fantasize about marrying their fathers. Meanwhile, young children have a tendency to anthropomorphize everything, to attribute the full range of human consciousness, intelligence, and motivation even to inanimate objects. So of course little Guillermo would see the gill-man as an appropriate love interest for Kay Lawrence. The central, and maybe even fatal, flaw of The Shape of Water is that del Toro remains too enamored of his childish fantasy to look at it through adult eyes, to see how much work must be done on the premise before it makes sense on adult terms. The Shape of Water never properly earns its fish-fucking, and worse still, del Toro never seems to recognize that it needs to.

What’s missing is a sense of the gill-man’s personhood, or alternately a sense that Elisa is so isolated and damaged that lack of personhood isn’t a deal-breaker for her. Consider Abe Sapien, the gill-man from Hellboy. He may be a fish, but he’s also clearly a person, mentally and morally equivalent to a human being. Abe thinks with the same degree of depth and complexity as you or me, experiences the same range of emotions in seemingly the same way, possesses the same level of self- and other-consciousness. It’s not too great a stretch to imagine a sufficiently open-minded human falling in love with his mind and eventually acquiring a taste for his body, even despite the chill and the slime and the scales and the smell. This gill-man isn’t another Abe Sapien, though. At no point does it ever exhibit any behavior that necessarily requires human-like cognition or psychological development. Indeed, what I kept thinking of as I watched The Shape of Water was Koko, the celebrated signing gorilla. Koko’s use of sign language and other advanced communicative behaviors seems to indicate that there’s more going on inside an ape’s head than was once believed, but the way she employs them demonstrates just as forcefully the limits of the simian mind. The same seems true of Elisa’s gill man, although the data set there is admittedly much smaller. I think it’s safe to say that we’d all be rightly appalled if one of Koko’s handlers smuggled her out of the lab one day and started having sex with her, yet The Shape of Water offers no credible basis on which to distinguish Elisa’s actions from that hypothetical Koko-banging.

Of course, making the gill-man unquestionably sapient wasn’t the only way del Toro could have explained Elisa’s case of pond-bottom fever. There’s a darker version of this story to be told in which Elisa doesn’t care about the gill-man’s inhumanity because she doesn’t see herself as fully human either. To be fair, The Shape of Water flirts a bit with this approach by playing up the way people like Strickland react to Elisa’s muteness, and by introducing an inconclusive nub of a hint that she, with her mysterious parentage and suspiciously gill-slit-like neck scars, is some kind of mer-changeling. The trouble, on the first count, is that Strickland is very much an outlier among Elisa’s acquaintances. With Giles, Zelda, Mr. Arouzmanian, and even Hoffstetler in his way having her back, it just isn’t credible for Elisa to be all, “Nobody likes me, everybody hates me— I think I’ll fuck this fish.” And on the second count, the mer-changeling business sits there so inertly throughout most of the film that it feels less like a justification for Elisa’s behavior than like a vestigial appendage carried over from del Toro’s earlier, fairy-tale-inflected work.

Nor is it even possible to write off the coupling between Elisa and her hot piece of bass as merely symbolic of some other disfavored form of relationship. Elisa’s friendship with Zelda crosses the color line, so race relations need no symbol to hide behind here. Homosexuality does a perfectly good job of representing itself, too, in the subplot about Giles trying to hook up with the counter hop at his favorite pie shop. Elisa is already disabled, so the movie has that covered as well without resorting to allegorical bestiality. If the fish-fucking is supposed to be a metaphor, del Toro has left it precious little space to be a metaphor for anything. And that leaves us right back where we started, groping for any psychologically convincing reason for this woman to have sex with that thing. I’ve been in del Toro’s corner ever since I saw Pan’s Labyrinth, and I’m gleeful at the sight of so many people fawning in public over the most perverted goddamned thing to slither through a suburban multiplex in a decade at least, so I wish I could join in the celebration on The Shape of Water’s behalf. But then I remember again what it feels like to touch a live fish with bare hands, and— ICK! No!

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact