Satan Exultant / Satan Triumphant / Satana Likuyushchiy (1917ó fragmentary print) [unratable]

Satan Exultant / Satan Triumphant / Satana Likuyushchiy (1917ó fragmentary print) [unratable]

So it turns out the Germans and their cousins to the north werenít the only ones whose film industries started dealing in diabolism as the last centuryís teen years gave way to the 20ís. In fact, it appears that the Russians beat them to it by a few years. My first hint of the existence of a Czarist Satanic cinema came in 2011, courtesy of Wrong Side of the Art. That summer, the aforementioned website published scans of an eye-catching poster for Yakov Protazanovís Sin and an absolutely astonishing one for something called Married by Satan. The miserable survival rate of Russiaís pre-Revolutionary films was such that I despaired of ever actually seeing those movies or any others like them that might have been made, but as it happens, I did so at least a tad prematurely. Bits and pieces of Married by Satan still exist, to the tune of perhaps 20 minutes altogetheró although most of the extant footage reportedly focuses more on marital melodrama than on the witchcraft-and-possession aspect of the plot. And while Iíve heard nothing yet to suggest even the partial survival of Sin, I unexpectedly lucked into some of Protazanovís other work when I borrowed a friendís copy of Viy. Among the extras on the disc were the last act of Protazanovís Pushkin adaptation, The Queen of Spades, and more to the point, about 20 minutesí worth of fragments from the first installment of Satan Exultant. The latter feature was a generational saga so sprawling that it had to be released in two parts (which is to say that it was roughly as long as a normal movie today), and it strongly foreshadowed such later Teutonic excursions down the Left-Hand Path as Satanas and Leaves from Satanís Book. It concerns the family of a stuffy yet secretly dissatisfied clergyman, and how they are brought to grief by the machinations of a disguised Prince of Darkness.

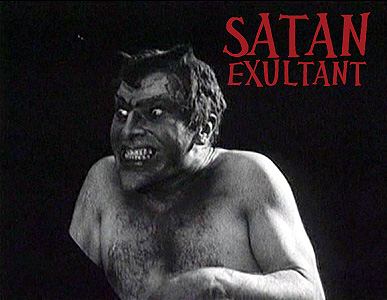

Todayís English-speaking audiences will no doubt snicker at the intertitle that opens this assemblage of Satan Exultant: ďA dark, stormy night.Ē On this Bulwer-Lyttonesque eve, the pastor Talnoks (Ivan Mozzhukhin, from The Queen of Spades and the 1915 version of Ruslan and Ludmila) looks out the window to observe the violent weather and remarks to his brother, Pavel (Pavel Pavlov), that it looks like God himself is about to come down from Heaven and give mankind a piece of his mind. Hehó not quite. One of the great cosmic powers will indeed be putting in a personal appearance on Earth tonight, but it isnít going to be God. Whatís more, when Satan (Aleksandr Chabov) heads upstairs to the Material Plane, he makes a beeline for the pastor and his family. Posing as a lost and injured traveler, the Devil tricks Talnoks into putting him up for the night. Thus begins a stealthy but intensive campaign of soft-sell temptation, directed first at Talnoks himself, then at his brother and sister-in-law, Esther (Sinís Natalya Lysenko). Satan gradually opens the pastorís eyes to all the fleshly pleasures denied him by his dreary Puritanism, from the scent of flowers to the buzz of wine to the incomparable aesthetic symphony of physical intimacy. To the artistically inclined Pavel, he suggests that representations of his lovely wife would be a much fitter application of his talents than the religious subjects heís preferred to paint thus faró and he also hints that Pavel hasnít been pursuing his husbandly prerogatives with half as much vigor as he might. And to Esther, the Devil draws a valid but insidious comparison between the homely, hunchbacked Pavel and his handsome, charismatic brother. Soon, Talnoks and Esther are in torment over a theoretically unwelcome mutual attraction, and their tight-knit little family is noticeably fraying around the edges. Then one afternoon, Talnoks makes an impulsive visit to an antique shop, where he stumbles upon a 200-year-old drawing that depicts his troublesome houseguest in his true form. Of course, by that time, the damage is already done.

For the rest of the story, Iíve had to do some digging. Apparently the Satanically provoked attraction between Talnoks and Esther blossoms into a full-fledged affair, while the pastor becomes so obsessed with the old drawing that he steals it, and puts it up in a private space in his church. Esther becomes pregnant with the ministerís child, which doesnít exactly do wonders for Pavelís relationship with either of them. Then both men are killed in a strange and possibly supernatural accident in the church, and part one reaches its conclusion. Part two takes up 20 years later, with the bastard Sandro (also played by Mozzhukhin) grown to young adulthood and living in the big city. He too meets Satan, this time in the guise of an urban dandy, who pushes him to pay court to a society dame called Inga (Vera Orlova, from Aelita: Queen of Mars) in a manner neither tasteful nor Godly. Esther understands the significance of her sonís new friendship, and she begins searching for the antique drawing in the hope that by destroying it, she can lift at last the curse that weighed on her family since the night they took in that bedraggled drifter.

I was both encouraged and annoyed to discover that the Russian Cinema Council print of Satan Exultant is not the most complete one out thereó encouraged because that means thereís a decent chance that Iíll eventually get to see more of this odd and fascinating film, and annoyed because the nearly-whole 87-minute cut is not currently available on home video. For now, this shriveled and inconclusive nub is the only game in town, barring a revival screening like the one that put me in touch with The Heavens Call some years ago. What I watched works almost like a hyper-extended trailer, raising more questions than it answers, and tantalizing more than it satisfies. Mind you, even catching up with the best extant print wonít answer all of those questions, because both parts are reportedly missing their final acts.

Thereís something very unusual about Satan Exultant, but it may be invisible at first to many Western viewers. Notice that Talnoks is described throughout as ďpastorĒ rather than ďpriest.Ē Notice also that he refuses wine on the grounds that itís sinful to drink alcohol, and the gift of a flower from one of his congregationists on the grounds that prettying up his house with such things would be tantamount to encouraging vanity. Finally, look at the way he dressesó that heavy, black suit with the contrasting white, two-piece collar. He looks just like Vincent Price in The Conqueror Worm, doesnít he? Put it all together, and Iím inclined to believe that weíre meant to take Talnoks for a Protestant of some kind, which raises some important issues of interpretation. Protestantism is very much a minority religion in Russia, and was even more so in 1917. If Talnoks is Protestant, it almost has to mean somethingó but what? Well, letís think for a minute about the usual role of religion in stories like this one. Traditionally, Christianity serves two purposes in tales of demonic intrusion: protection against direct attack by evil beings, and reinforcement of the will to resist and withstand temptation. Talnoksís faith does him no good at all in either capacity, so are we supposed to read his spiritual defeat as a sign that his alien Christianity is inferior to the homegrown Russian Orthodox variety? Would an earthier Orthodox Christian have been less susceptible to Satanís argument that the pastorís religious strictures were preventing him from living life to its fullest? Or alternately, is it possible that Protazanov was counting on his countryís censorship authorities (who were not yet Communist when Satan Exultant was under production) to make that conceptual leap themselves, and therefore to give a pass to material that might otherwise raise conservative hackles? I donít know, but it seems impossible to me that there isnít a hidden back-story here.

Whatever the motive for framing the conflict in exactly these terms, the interaction between Chabovís jolly Satan and Mozzhukhinís dour Talnoks is often a joy to watch. As usual in these cases, my sympathies lie solidly with the Devil, and Chabovís broad, hammy performance is the movieís biggest single source of sheer fun. This is a Lucifer who loves his job, whose enthusiasm for sin is simply infectious. Thereís at least as much to appreciate, though, in Mozzhukhinís tortured slide from brittle piety to clandestine vice. Mozzhukhin was considered one of Russiaís foremost screen actors during this period, and his fame was such that after fleeing the Russian Civil War in 1919, he became the central figure of a Paris-based ťmigrť filmmaking scene. Later still, he was lured to Hollywood, but that sojourn didnít go as well, even after he submitted to studio pressure to have his hawkish features softened by plastic surgery. Itís easy to see why he was so highly regarded in Europe. Although it inevitably looks stiff through modern eyes, Mozzhukhinís performance in Satan Exultant displays a then-uncommon awareness of the differing demands of stage and screen. A comparison with A. Oromov in The Portrait is especially instructive. Oromov is a fine example of what is often disparagingly thought of as ďsilent movie actingĒó which is to say that itís really 19th-century stage acting ported over into a medium that requires something else very much subtler. Mozzhukhin was at the forefront of developing that something else. His present obscurity suggests that his contributions to the evolution of movie acting remained almost as small as they would have been had he stayed at home to be murdered by Trotskyís minions, but I donít doubt that he did contribute. Just look at him hereó see how far ahead of the curve he is, and remember that heíd be in France two years later. Here, too, I see hints of a hidden back-story, only this time the foreground plot being influenced is the maturation of cinema as a whole.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact