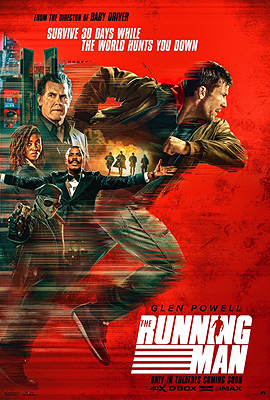

The Running Man (2025) **½

The Running Man (2025) **½

Stephen King himself found it rather odd that two of the original five novels he published under the pseudonym Richard Bachman were near-future dystopias involving lethal competitions akin to television game shows. By his own admission, King has never been given to planning out his writing ahead of time, and that wasn’t something he deliberately set out to do. I don’t find it odd at all, though, that both of the books in question should get film adaptations in a year when a former TV game show host is doing his bumbling but determined damnedest to complete America’s quarter-century transformation into a dysfunctionally authoritarian dystopia in the real world. Indeed, when you look at it like that, The Long Walk and The Running Man really are tales whose times have come. Also, in The Running Man’s case specifically, I’m sure it didn’t hurt that the source novel happened to be set in 2025. On paper, Edgar Wright seems like an excellent choice to direct the latter adaptation, since the 2025 we actually got is as clownish and absurd as it is grim and unjust. Who better to capture that mood than a maker of dark comedies like Shaun of the Dead and The World’s End? But dark comedy isn’t quite where this version of The Running Man ended up, and Wright’s instincts in that direction help lead the film astray when it counts.

Heaven knows there’s nothing funny about the note on which The Running Man opens. Industry-hopping hardhat foreman Ben Richards (Glen Powell) has come to see one of his former bosses about maybe getting his old job back. His infant daughter, Cathy, is seriously ill, but he and his wife, Sheila (Jayme Lawson, of Sinners), can afford only palliative medicine on just her wages as a nightclub hostess. Now maybe there’d be an opening for Ben if it were merely a question of qualifications or quality of work, but the thing is, Richards is an inveterate do-gooder, which makes him also an incorrigible squeaky wheel. You can see why that would be frowned upon in a world of all-powerful corporations and disposable labor, where employees are expected to shut the fuck up and be grateful for what they get. In his last position, Richards went so far as to try organizing a union, and that’s about as big a no-no as there is. Ben’s been on the blacklist ever since, and that’s where he’s going to stay.

There are, however, ways of getting money without getting a job— and I’m not even talking about crime, for which Ben lacks the temperament anyway. His era may be stingy about bread, but it goes in big for circuses, and among the mightiest of the corporations is the Network, which holds a functional monopoly over broadcast television (or Free-V, as people call it nowadays). The Network’s most popular offerings are its game programs, which pit the desperate against cruel and spectacular challenges, but pay more, even at the lowest levels, than Sheila could earn in a month. And the biggest show, “The Running Man,” doles out prizes that could permanently change a contestant’s life. Sheila wants nothing to do with any such scheme, though, for the entirely sensible reason that it isn’t just the contestant’s dignity on the line in these games. The viewing public has reverted to Roman tastes, and even the least remunerative of the Network game shows carry a risk of severe injury or even death. What the hell would she and Cathy do if Ben came home with a broken leg that they couldn’t afford to fix, or even worse? You know how men get, though, when their status as providers is called into question. Besides, Ben is fit, strong, tough, clever, and exceedingly resourceful— and he’s never worked a job in his life that couldn’t have killed him in a hundred ways if he hadn’t been all of those things. So really, what’s the difference?

The difference, as Richards discovers only after he’s undergone the full screening process for Network game show contestants, is that applicants get no say in which show they’re ultimately assigned to. All those medical, physical, and psychological evaluations match each man or woman subjected to them with the show on which the Network’s algorithms reckon they’d prove most entertaining to watch. And Richards? He’s “Running Man” material through and through. Now it’s possible to spin that as good news. “The Running Man” is the highest-rated show on the airwaves, and the grand prize is an utterly fantastical one billion New Dollars. Ben was ready to wager his life for just a few hundred if the odds were good enough. Also, you don’t even have to win on “The Running Man” to cash in big. Just staying in the game nets you an ascending series of four-, five-, and six-figure purses, which you’re free to have sent directly to the designee of your choice. That would mean a whole series of big paydays for Sheila and Cathy back home. On the other hand, the odds against a “Running Man” contestant doing anything but dying fast and horribly are astronomical. The object of the game is to live as a fugitive, by any means in your power, for a full 30 days, documenting your continued survival with daily video mail drops running at least ten minutes each. Law enforcement officials nationwide are authorized to kill you on sight. So are private citizens, who are furthermore incentivized to do so with cash and prizes. Lesser rewards are available, too, for productive tip-offs, encouraging viewers who want in on the action, but lack the moxie to commit legally sanctioned homicide personally. Also, “The Running Man” employs its own in-house team of bounty hunters, led by masked man of mystery Evan McCone (Lee Pace, from Revolt and Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy). So basically all the world will be your enemy, Sucker with a Thousand Enemies. For all those reasons, competing on “The Running Man” was the one thing that Ben specifically promised Sheila he wouldn’t do. But Network president Dan Killian (Josh Brolin, of Weapons and Denis Villeneuve’s Dune) makes clear when he presents Richards with the contract face to face that “The Running Man” is what’s on offer. He can take it or leave it. Ben decides to take it.

What Richards doesn’t realize when he and his fellow targets, Jenni Laughlin (Kat O’Brian, from Queens of the Dead and Gnawbone) and Tim Jansky (Martin Herlihy), set out on their respective runs, is what a complicated relationship fans of “The Running Man” have with the contestants. True, host Bobby T (Colman Domingo, of Candyman and Transformers: Rise of the Beasts) makes a big production of vilifying the runners, using a mix of verifiable half-truths and outright fabrications to portray them as the worst sort of human scum, while McCone and his Hunters are elevated to the status of Real American Heroes dispensing the only form of justice such lowlifes deserve. But the thing is, everyone not privileged to live in the exclusive urban districts surrounding the various corporate headquarters compounds hates the system every bit as much as Ben has grown to, and wants to see it all burn in their heart of hearts. A successful antisocial degenerate can therefore become a folk hero at the pull of a trigger. So the longer Richards runs, and the longer he outlasts his less adept competitors, the more help he’s likely to attract. Some of that help, naturally, will come from old friends, like Molie (William H. Macy, from The Last Dragon and Jurassic Park III), his neighborhood’s dealer in all things less than legal. Some of it will come from idealistic young people, like the brothers Stacey (Angelo Gray) and Bradley (David Ezra), the latter of whom makes whatever this future has instead of YouTube videos seeking to expose the chicanery and sleight of hand behind what’s shown on the daily broadcasts of “The Running Man.” Some of it will come from madmen in search of a blaze of glory to go out in, like Elton Parrakis (This Is the End’s Michael Cera), the grudge-holding son of a policeman turned hotdog-vendor. Some of it will even come from members of the comfortable class like Amelia Williams (Emilia Jones), shaken by the difference between a runner met in person and one as seen on Free-V. But a substantial amount of help will come from the Network itself, and if Ben wants to reach day 30 alive, he’d do well to figure out how and why that is.

In book form, The Running Man had the most audacious ending of Stephen King’s career. Backed into a corner by the failure of a desperate endgame bluff, Richards hijacks the plane carrying him to a high-stakes meeting with Killian, and crashes it into Network headquarters. This is portrayed as the happiest ending available under the circumstances, and it sure as fuck feels that way when you read it. Obviously there was no way in hell anyone would have the brass-balled gall to use “9/11 can be good, actually” as the conclusion to a Running Man movie in the 21st century, but that left Edgar Wright and co-writer Michael Bacall with a rather serious problem. It isn’t just that Ben’s kamikaze attack on the Network feels triumphant in King’s original telling; more importantly, it feels inevitable. Everything in The Running Man’s world is so thoroughly and meticulously rigged against people like Richards that there was never any way for him to win— not really. The best he can do is to force the most devastating possible draw, leaving society to pick up the pieces however it sees fit. For Wright’s purposes, that meant that if he wanted to do something else with the ending, then he had to do a whole lot of other something elses first. Wright ducked that part of the assignment, leaving all of King’s buildup basically intact, even though he couldn’t use the only denouement to which it could plausibly be building. This movie’s much more hopeful, much more conventionally happy ending consequently feels like a colossal cheat, and retroactively cheapens everything that comes before it. What was shaping up to be exactly the Running Man adaptation that 2025 deserved turns at the last into the Running Man adaptation for 2014, leaving not a sour or bitter taste in the mouth, but a cloyingly sweet one instead.

Part of what Wright got wrong in the end is tonal. The diversion from the course of the novel is announced by Bradley, in the guise of “the Apostle,” his YouTube (or whatever) alter ego. That means it’s calibrated to the tastes of his internet-addled subscribers, and functions as a broad satire of online influencer culture. It’s… kind of funny, I guess? But it comes much too late in the film for the introduction of a whole new critical thrust, and at a point in the narrative when it’s self-defeating to crack a joke at all. You could argue, though, that Wright already warned us, during the Elton Perrakis episode, that something of that nature was on its way. Michael Cera can’t help doing his Michael Cera shtick, even if only in muted form, and from the moment he appears onscreen, The Running Man acquires a confusing note of misplaced goofiness. It’s especially evident whenever Perrakis interacts with his mother (Sandra Dickinson, of Tormented and Space Truckers), who is at once hopelessly senile and utterly vicious. And the battle against the police that closes out the Elton segment is like a Home Alone sequel with the lethality dialed up to maximum. None of the levity in the main plot, even at its darkest, lands half as well as the glimpses we get into the world of Free-V, which suggests what’s ultimately amiss here. The purpose of the Free-V clips is to establish an alternative frame of reference totally at odds with Richards’s experiences in the real world, a way of seeing much coarser, shallower, and stupider than anyone on the sharp end of this society can ever afford to be. That purpose is undercut by anything blurring the distinction between Free-V and real life, which is exactly what happens whenever Wright goes for a laugh that isn’t televised.

Mind you, the mere fact that such a mistake was available to Wright in the first place shows how clearly he understood the potential relevance of a new Running Man adaptation. At all points, this version does better by the source material than the one from 1987, and until things start to come unglued in the third act, it does better by the audience as well. Wright and Bacall sensibly removed or minimized a number of curlicues in the original premise rooted too specifically in the malaise of the mid-70’s to be anything other than distracting today (the distinction between Old Dollars and New, the virtual extinction of internal combustion engines in favor of feeble motors powered by compressed air, and so on), and redoubled the emphasis on class cleavage. Meanwhile, although some of the specific touchstones referenced by Wright are just about at their expiration dates, it was a canny move to increase the film’s emphasis on the funhouse-mirror aspect of Free-V. The mass media of the 1970’s were often accused of anesthetizing the population, but they had nothing to match their present-day counterparts’ capacity to offer entire parallel universes of bespoke “facts” tailored to the individual consumer’s most cherished prejudices. In much the same way that habitual viewers of Fox News are quantifiably worse informed than people who watch no television news at all, it’s impossible to imagine a steady diet of Free-V as presented here leaving one capable of understanding anything.

The last thing I want to mention before taking my leave of The Running Man is the casting, which is a strangely mixed bag. This is another entry for the ever-growing list of 21st-century films in which the leading man is a negative space in the picture formed by far more vivid supporting players. Glen Powell isn’t bad, but he’s ultimately just one more conventionally handsome blond dude whose big muscles belie his small screen presence. Everyone around him makes a much stronger impression. Josh Brolin, Lee Pace, and Colman Domingo are all outstanding as the three faces of the Network’s evil, although I do wish we’d seen more of Pace in particular. (Indeed, I kind of wish Pace and Powell had exchanged roles, since Pace’s wounded weariness is exactly what Ben Richards is lacking, while Powell’s lab-grown Hollywood pseudo-charisma would be interesting to see in a villain.) I was also left wanting more of Jayme Lawson’s Sheila and Kat O’Brian’s Laughlin. Lawson’s combination of soft-hearted compassion and hard-headed practicality brings into focus the sheer waste of human ability that inevitably comes with this degree of social stratification, while O’Brian is a chaotic delight as Ben’s foul-mouthed, sharp-dressing, skirt-chasing, punch-throwing fellow contestant. Even the folks like Cera and Dickinson often make a good show of a bad idea, sticking in the memory in ways that poor Powell unfortunately just doesn’t.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact