Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest (1908) [unratable]

Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest (1908) [unratable]

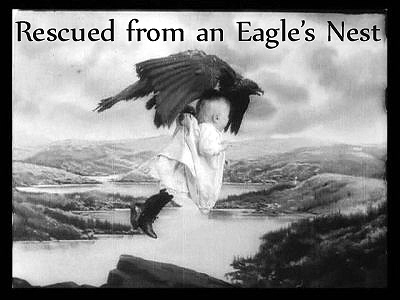

I want to bring up the issue of genrefication again, because there’s an aspect of it that we still haven’t talked about. At least in the movies, genrefication tends to be a pretty fast-acting process. Elements of an as-yet-unrecognized genre might surface here and there for decades, but when they all come together in a way that enables people to speak intelligibly of a swashbuckler or a space opera or a locked-room mystery or whatever, it usually doesn’t take but five years or so for the parameters of the new genre to be defined, or for the formulas associated with it to become more or less fixed. Frequently, though, there are freak outliers— films made long before a genre was codified that nevertheless fit into it as neatly as if they had been designed with its expectations in mind. Consider the animal attack movie, for example. Obviously, killer animals had figured in films of all kinds since the beginning of narrative cinema. Roman gladiators and Christian martyrs fought lions in the arena; jungle adventurers battled tigers and boa constrictors while searching for the treasures of extinct civilizations; frontiersmen contended with wolves and grizzly bears while taming the Wild West; evil masterminds dangled helpless heroines over alligator pits in their lairs. But it wasn’t until the 1970’s, when everything with teeth, talons, or tentacles suddenly went into business exacting Mother Nature’s Revenge, that the animal attack movie emerged as a category unto itself. Only then did films in which the central conflict was between homicidal animals and their human prey, unmotivated by the designs of any human (or human-like) antagonist, begin appearing in sufficient numbers to be seen as a full-fledged genre. And yet there were animal attack movies in that fully modern sense previously— just not enough of them for it to become apparent except in retrospect that that’s what they were. Most famously, it’s difficult to imagine The Birds turning out any differently had it been made in 1977 instead of 1963. And a decade before that, The Naked Jungle dedicated its second half to a story that would have raised no eyebrows in the company of Tarantulas: The Deadly Cargo, It Happened at Lakewood Manor, and The Swarm. Well, now let me tell you about the freakiest and most outlying freak outlier I’ve found yet within the animal attack genre. In 1908, the Edison Company released a seven-minute film called Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest; I first encountered it in a compendium of Edison shorts that aired on Turner Classic Movies a couple years ago, and I could barely believe my eyes.

Out in the woods of what I take to be rural New York lives a lumberjack (D. W. Griffith, who at this stage of his career was merely the actor from Cupid’s Pranks and The Sculptor’s Nightmare, rather than the director of The Avenging Conscience and One Exciting Night), together with his wife (the enigmatic “Miss Earle”) and their infant daughter (Jinnie Frazer). One morning, after the man of the house has tromped off to join his fellows in a hard day of cutting down trees, skipping and jumping, and going to the lavatory, the woman sets the baby down in front of their cabin to play. The little girl is soon noticed by an eagle, which swoops down from the sky and carries her off. Mom hears the resulting commotion, but comes too late to do much about it. The bird has already flown out of arm’s or stick’s or stone’s reach, and it takes the woman only a moment to realize that trying to shoot it out of the sky would be much too risky. So instead of taking any immediate offensive action, the mother tracks the eagle to its nest, then dashes off to find her husband and the other lumberjacks. Luckily, she reaches the worksite before they’ve knocked off for the day to put on women’s clothing and hang around in bars, so the whole lot of them (including Henry B. Walthall, later of The Raven and London After Midnight) hurry to her aid. The trouble is, the eagle’s nest is on the face of a sheer cliff. The only way to reach it is to go around to the top the long way, and then lower the girl’s father by rope to the relevant ledge. He gets there just as the eagle comes home from wherever birds of prey go during the day, which rather complicates the business of rescuing his daughter. Now he’ll have to fight the eagle in an environment which strongly favors it before he and his friends can hoist the child to safety.

This really could have been one of the “Meanwhile, back in town…” segments from the third act of Day of the Animals (although the baby would almost certainly not have survived if it had been). It’s bracing to see such a modern premise take so antiquated a form. And make no mistake— Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest is indeed formally antiquated. Director J. Searle Dawley (who may have been the scenarist as well— the Edison Company didn’t normally credit writers during this period) is better remembered for doing the same job on the Edison Company Frankenstein, a movie that often looks old-fashioned even for 1910. Dawley’s technique is essentially the same here, except that Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest has no intertitles. This movie even shares Frankenstein’s quirk of breaking up what is otherwise a uniform succession of medium shots composed in stage-play fashion with a relative close-up on the main special effects set-piece early on. In the later film, that set-piece was the creation of the monster; here, it’s the flight of the eagle over the New York countryside with Jinnie Frazer clutched in its claws. In each case, it’s the most visually interesting thing the movie has to offer, despite some inevitable crudity, and giving it the extra attention implied by nearer camera placement was a smart move. The flight scene here is also interesting for what it inadvertently reveals about how Dawley dealt with actors and characters. I would be tempted to call Jinnie Frazer’s performance during her abduction the thespian highlight of Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest, but it’s obvious that the poor kid was genuinely terrified to be hung beneath the belly of the big, clumsily flapping eagle puppet. Nevertheless, Frazer’s unsimulated sobbing provides one of only two glimpses the movie offers into the hearts or minds of the characters. (The other is the well-observed moment when the mother takes aim at the eagle with a shotgun, hesitates, and then puts the weapon down unfired.) For the remainder of the film, the actors might as well be props just like the eagle. It’s here, I think, that we see how backward-looking Dawley’s direction really was. He isn’t even treating Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest as a stage play on film; instead, he’s treating it literally as a moving picture, and himself as a photographer who has acquired the ability to capture a bit more than just a single, inanimate instant of the action he wishes to depict.

Paradoxically, I suspect that it’s precisely because Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest is so ancient (and so conservative even for its age) that it prefigures the killer critter movies of 70 years later so exactly. Storytelling in this era of cinema history was by necessity very basic, very rudimentary. All of the action had to fit into fifteen minutes or less (the length of a single film reel at then-standard projector speed), and it had to be understandable not only without dialogue, but without even the scene-setting crutch of an intertitle. There was no room for character development, no room for complex plots or hidden motivations. “Parents fight bird over baby” was a story that filmmakers of Dawley’s generation and mindset could tell with the tools at their disposal. Even if they had preferred to chronicle the hardscrabble existence of an Upstate New York logging family (who one day had to rescue their baby from a killer eagle) instead, the technology and the business model of motion pictures in 1908 would not readily have supported that. It is fascinating, though, that by doing what they could with what they had, Dawley and his collaborators gave us on this occasion something whose time would not truly come for almost seven decades.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact