Polyester (1981) -****

Polyester (1981) -****

Polyester is probably the best movie John Waters ever made. It’s also the most frustrating, because it points down a road not taken, and that road leads to place much more interesting than those where Waters actually went subsequently. Up through certainly Female Trouble and maybe even Desperate Living, Waters’s films can be looked at as a reaction to his experiences coming of age in the 1960’s, in a place that was not exactly the nexus of American cosmopolitanism. They’re all about misfits rebelling against a culture that lacks any constructive way of dealing with nonconformity: Lady Divine and her Cavalcade of Perversions, the Filthiest People Alive, Dawn Davenport and the Dashers, the residents of Mortville, the assorted random weirdos who populate Mondo Trasho. There’s nothing wrong with that, certainly, but as the 1970’s wore on, Waters’s original “too freakish even for freakdom” pose became less and less tenable. Socially speaking, one of the most distinctive characteristics of the 70’s was the proliferation of countercultures, and the encroachment of counterculture values upon even the stuffiest preserves of the mainstream. By the 80’s, even those who presented themselves as defenders of normality had become intensely strange. After all, it was self-identified conservatives that put a B-movie actor who thought air pollution was caused by trees into the White House, that embraced the imaginary economics of the Austrian and Chicago Schools, and that made respected spiritual authorities out of men who claimed to heal the sick by laying on hands via cathode ray tube! The world was not the same place it had been in 1969, and if Waters wanted to maintain his justly earned standing as a guru of the bizarre, he would have to find new ways of relating to it in his films.

Polyester did much more than that. While dialing back only slightly on the sheer grotesquery that was formerly his primary claim to fame, and continuing to refine his now-iconic esthetic of sleaze and trashiness, Waters showed himself to be a genuinely incisive satirist. The new decade was but a year old, yet Polyester demonstrates that Waters already had its number. Instead of the self-aware outcast freaks of his 70’s movies, Polyester presents social-climbing freaks who don’t just desperately wish to be normal and respectable, but have somehow fooled themselves into believing that they already are. Those freaks’ foes, meanwhile, are now con-artists eager to exploit their insecurities, and to profit from the lies they’re already telling themselves. This was an enormously rich vein Waters had struck, and there was much more to be extracted from it. Instead, though, Waters took a seven-year holiday from filmmaking, and when he returned, it was straight back to rehashing the days of his adolescence. That’s why Polyester frustrates me. It hints at a version of Waters’s career that moves forward, taking on the fresh absurdities of each new era and reflecting them back in confrontationally tasteless form.

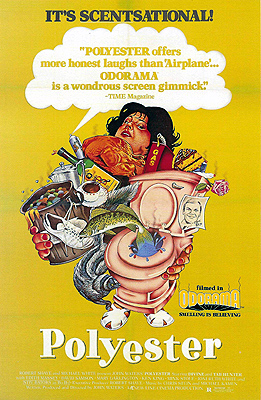

I believe I’ve mentioned before that it was John Waters who turned me on to William Castle, via the chapter, “Whatever Happened to Showmanship?” in his essay collection, Crackpot. Polyester begins by paying tribute to Castle, with an introductory segment in which Dr. Quackenshaw (Rick Breitenfeld, then the executive director of the Maryland Center for Public Broadcasting!) explains the workings of the miraculous Odoramatm process. With this wonderful new technology, it is possible for the audience to smell the very same aromas as the characters in the film, just as if they were there! You guessed it— it’s a scratch-and-sniff card. Like all the best Castle gimmicks, Odoramatm is tied directly to the movie’s plot, for Polyester’s central character, Francine Fishpaw (Divine), is possessed of olfactory superpowers. No smell, however faint, escapes detection by her exceptional nostrils.

As you might have guessed, Francine is foremost among those self-deluding freaks I was talking about. She lives with her husband, Elmer (David Samson), and two teenaged children in the stridently middle class Baltimore-Annapolis suburb of Severna Park. Everything about the Fishpaws’ material life reflects Francine’s longing for status and solidity, but the family is actually not that far removed from the other Divine-led clans in the Waters oeuvre. They owe their considerable income to pornography, for Elmer owns the snidely named Charles Art Theater downtown. (In real life, the Charles truly is an art house— albeit an art house suitably rough-edged for a city best known abroad for crime, dope, and venereal disease. In fact, the Charles was where I watched Polyester for this review.) Daughter Lulu (Mary Garlington) is not only dating the biggest hoodlum in her high school (Dead Boys frontman Stiv Bators), but is for all intents and purposes practicing for a career as a sex worker, selling salacious tabletop dances to crowds of horny boys in the cafeteria. And Dexter, the baby of the Fishpaw family (Ken King), is living a secret double life as the Baltimore Foot Stomper, the perverted sex maniac who’s been terrorizing the city and its environs for months. It’s more than enough to make Francine a pariah in the neighborhood, but her problems don’t end there. Her hateful mother (Joni Ruth White, from Street Trash and Smithereens) covets the money Elmer’s theater pulls in, and steals from Francine every chance she gets. Elmer, meanwhile, treats his wife no better, and he’s having an affair with his secretary, Sandra (Mink Stole, with her hair done up in a hideous mockery of the blonde cornrows Bo Derek wore in Ten). So far, Francine has done a remarkably thorough job of not noticing all the fucked-up shit in her life, but however tightly closed she keeps her eyes and ears, that nose of hers is going to turn up the evidence she doesn’t want to acknowledge sooner or later.

Naturally, the first step is for Francine to smell Sandra’s perfume on Elmer’s clothes. That leads her to enlist her former maid and current best friend, Cuddles Kowalski (Edith Massey), to spy on Elmer. (Cuddles’s back-story is practically Polyester’s satirical thesis statement. She left Francine’s service when the state lottery made her a millionaire, and now she’s doing her damnedest to live down to every stereotype about the nouveaux riches you’ve ever heard.) Cuddles and her loyal valet, Heinz (Hans Kramm), catch Elmer in the act at the White Gables motel (which stands about fifteen minutes up Route 3 from my house, incidentally), and alert Francine. Francine storms right over to the motel to demand a divorce, but getting Elmer out of the house merely opens the floodgates on her troubles. As he and Sandra launch a concerted campaign to torment and humiliate her, she descends into alcoholism, her children are institutionalized, and her mom even winds up in the hospital thanks to a shootout in the living room with Lulu’s boyfriend. Then, just as Francine hits rock bottom, she meets and falls in love with Todd Tomorrow (Tab Hunter, from Grotesque and War-Gods of the Deep). Finally, something goes right for her! But if you know anything at all about the tropes of tawdry melodrama, then you also know that Francine’s newfound hope can’t possibly be anything but false.

Now that is how you make a good bad movie! As is generally the case with the young (or young-ish) Waters, Polyester’s badness is purely superficial, its tastelessness and artlessness tools in service of hidden skill and intelligence. Its absurdities are purposeful, no matter how far over the top they climb, as is the calculated incompetence with which the non-actors who comprise most of the cast bring them to lurid life. Consider, for instance, Cuddles and her debutante ball. Not too long after the release of Polyester, essayist and culture historian Paul Fussell wrote a book called Class, in which he anatomized in humorous but well-argued manner the socioeconomic structure of the Untied States in the 1980’s; his thesis was that class insecurity was a major driver of American culture, and that at each rung of the ladder, that insecurity was visible in increasingly ludicrous displays of misappropriated and misunderstood status symbols assumed to be associated with the next few up. Naturally, even Fussell could give no real-world example to equal a 70-year-old woman throwing a debutante ball at the Fontaine Bleu in Glen Burnie (a reception hall of the sort where high schools hold their proms and shystery, ambulance-chasing law firms hold their holiday parties), but the difference is one of degree only— and Waters got there first. He saw that to a greater extent than any decade since the 50’s, the 80’s were going to be about putting on airs and faking virtue, so how better to poke fun at that than to pose one of his usual bands of reprobates as the epitome of middle class values?

There’s yet another layer to Polyester, though, and this one I would never have noticed on my own; for the remainder of this review, I’m heavily indebted to Jessica “Juniper” Ritchey, whose interests and tastes extend into regions where mine never venture. One of those regions happens to be what used to be called “weepies,” “four-hanky films,” and perhaps most condescendingly of all, “women’s pictures.” During the 40’s and 50’s— the latter decade especially— Hollywood sought to tap the same audience as TV’s soap operas by producing florid melodramas about women who just could not catch a break. It was yet another front in the battle for attention between cinema and television that we’ve so often discussed in the context of gimmicky mid-century horror and sci-fi movies. Anyway, the acknowledged master of the four-hanky genre was Douglas Sirk. Like any contract director, Sirk made all kinds of movies over the course of his career, but what he’s remembered for are seven or so romance pictures with plots so convoluted and emotions of such shrill pitch that modern audiences often find it difficult to believe that they were meant to be taken seriously. To cite just one very famous example, Magnificent Obsession has a rich prick inadvertently cause the death of a saintly doctor when the rare and expensive lifesaving equipment that could have counteracted the latter’s heart attack is occupied in resuscitating the former’s stupid ass from a boat crash instead. The rich prick then manages to blind the doctor’s widow by precipitating a car accident, but she falls in love with him anyway when he vows to atone for his behavior by studying medicine and taking over the dead doctor’s clinic. Then the widow decides that she and the reformed prick can’t be together, because disabled people aren’t allowed to have romantic relationships or some such bullshit. She runs away, but they’re reunited years and years later when the widow comes down with a brain disease, and the ex-prick— now a saintly doctor in his own right— is the only man with the talent to save her. Naturally, the widow recovers her sight as a side effect of the operation, so the pair can get married after all. You see where I’m going with this, right? Polyester is a Douglas Sirk movie, John Waters style. Spend enough time digging through Sirk’s filmography, and you’ll find only slightly less overblown versions of nearly all this movie’s plot developments. Tab Hunter substitutes admirably for Sirk regular Rock Hudson, even to the extent of being another closeted gay guy! And Waters apes Sirk’s visual style with surprising fidelity, from color palette to frame composition to lighting effects. The music is spot-on, too, especially the opening theme song with Hunter slow-crooning Chris Stein and Debbie Harry’s satirical lyrics over cloying strings-and-piano schlock. I ask you: who else but John Waters would think to combine William Castle and Douglas Sirk as the active stylistic ingredients of a single film?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact