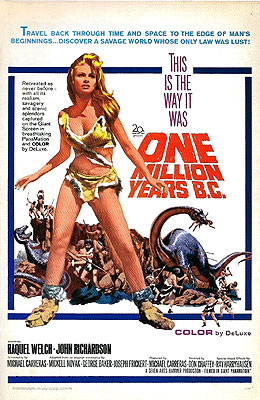

One Million Years B.C. (1966) **½

One Million Years B.C. (1966) **½

It’s really hard to do a good caveman movie. On the one hand, you have to worry about at least paying lip service to the latest paleontological and anthropological thinking, but on the other hand, you must address the need for drama and excitement. A movie that has its well-scrubbed, blonde cavemen running around speaking perfect English and facing at regular intervals a death-struggle against whatever the director’s favorite dinosaur happens to be is going to get laughed off the screen. But nobody wants to sit through an hour and a half of filthy, ugly people in heavy facial prostheses communicating with each other via primitive sign language while they forage for wild legumes and hunt rodents and lagomorphs. And there is a very good reason why no one would watch such a movie-- it would be about as much fun as doing the laundry for a little league soccer team. So the trick becomes finding the best way to steer a course between the two extremes. When Hammer Film Productions remade 1940’s One Million B.C. as One Million Years B.C. 26 years later, they ended up making a movie in which well-scrubbed cavemen run around speaking a very simple made-up language (which we’ll end up hearing spoken again with slightly more developed syntax in When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth) and face at regular intervals death-struggles against a wide array of creatures including, but not limited to, Ray Harryhausen’s favorite dinosaurs. And amazing as it may seem, the resulting film really is pretty decent.

What really sets this movie on a plane above most of its competition is the fact that the picture it paints of prehistoric society is not completely ridiculous (well, apart from that whole dinosaur thing). The primitive-man-as-brutal-savage angle is laid on a bit thick early on, but after the first twenty minutes, the film’s treatment of the subject is fairly believable, whether or not it reflects anything like the way life was really lived in prehistory. As One Million Years B.C. opens, we are introduced to the Rock Tribe, whose leader Akhoba (Robert Brown, from The Masque of the Red Death, whom you might also remember as M in the later James Bond movies) really has his hands full with his two sons. For one thing, the sibling rivalry between them is tremendous. Tumak, who seems to be the elder of the two (John Richardson, who spent most of his career working for Italian directors-- look for him in The Church, Eyeball, and Black Sunday), is also visibly the favorite, and little brother Sakana (Percy Herbert, of Craze and Island of the Burning Doomed) resents the situation intensely. But-- and this is the main reason Akhoba needs to be vigilant around his boys-- Tumak also seems to be noticing that the chief isn’t as young as he used to be, and that the time might be ripe for one of his sons to step up and take charge. Because Tumak is a no-shit guy, when he makes his move, he does so in the open, picking a fight with his old man over a pig’s leg. It turns out, however, that Akhoba is not so feeble as his gray hair suggests. He kicks his upstart son’s ass and banishes him from the Rock Tribe’s territory, leaving him to wander aimlessly, alone, across the Meso-Ceno-Paleozoic landscape (Yeah, well what would you call it? We’ve got modern vultures, sauropods, and giant tarantulas all living together here, to say nothing of that back-projection iguana that seems to get bigger with every change of camera angle...) until, starved and exhausted, he reaches the seashore and passes out.

Of course, you realize what lives by the seashore in just about every caveman movie ever made, don’t you? That’s right-- beautiful, blonde Cro-Magnon chicks, hunting fish and mollusks with their delicately worked, obsidian-headed fishing spears. All of which brings us to what most people who remember One Million Years B.C. mainly remember it for-- Loana (Raquel Welch of Fantastic Voyage, sporting the costume that made hers the most famous cleavage of the entire decade). Loana happens to notice Tumak lying unconscious on one of the dunes while she fishes, and she rushes over and attempts to revive him, but the huge stop-motion sea turtle that looms up over the top of the next dune on the left doesn’t think that’s such a good idea. Thus the pattern becomes set for the rest of the movie. We’ll get anywhere from ten to twenty minutes of plot, and then a monster will attack out of nowhere for no reason other than the filmmakers’ fear that the audience may become bored otherwise. Loana then demonstrates why her tribe is going to invent civilization in 20,000 years or so, while Tumak’s will still think fire is the epitome of modern technology until the day they are exterminated or enslaved by the more advanced bunch on the other side of the mountains. She produces a large seashell (from where I have no idea-- she certainly wasn’t hiding it in her bikini) and blows into it, summoning thereby a contingent of her tribe’s spear-wielding warriors to do battle with the big turtle. The turtle quickly decides that the half-dozen skinny, blonde hunters are more dangerous than they look, and lumbers into the sea, after which Loana and her people return to their village, carrying the now semi-conscious Tumak with them.

A word of advice: if someone from the Rock Tribe ever comes to your house for a party, make them leave! Loana’s people are as advanced socially as they are from a technical perspective. They have jewelry, houses, and a highly developed style of interior decorating as well as stone-tipped spears and conch-shell horns. Not only that, they don’t decide everything with a contest of strength-- their leader is about fifteen years older than Akhoba, and looks as though he weighs about half what Tumak does. And Loana’s people believe in sharing and hospitality. Tumak has it pretty good in the Beach Tribe’s village, particularly after he saves a small child’s life when the village is attacked by a fifteen-foot theropod (none of the beach people is as big or as strong as Tumak, and only he is anything like a match for the dinosaur), but the guy just doesn’t play well with others. Before long, he manages to get himself thrown out of their village too, again for picking a fight-- this time with Loana’s sort-of boyfriend Ahot (Jean Wladon). But Loana is by this time so smitten with Tumak that she follows him when he trudges off to begin his second banishment in as many weeks.

Meanwhile, back in the mountains, Sakana has picked up where his brother left off. He, too, covets his father’s power, and one day while the tribe is out hunting mountain goats, the sneaky fucker arranges for Akhoba to meet with a little “accident.” Akhoba survives, but he comes out of his fall from the cliff-face much the worse for the experience, and let’s face it, there’s little prospect for a man with one eye and a pronounced limp hanging on to any kind of authority in the Rock Tribe. The change in tribal leadership ends up being a good thing for Tumak, though, because when he makes his way back to the mountains with Loana in tow, he has only his weasely little brother to deal with, rather than his once-formidable father. Here begins a new phase in the two brothers’ rivalry that will ultimately lead to outright war between them, with about half of the Rock Tribe following Sakana, and the other half (plus the Beach Tribe, with whom Tumak eventually reconciles) lining up behind Tumak. (There are, of course, plenty of pauses in the story for dinosaur fights along Tumak’s and Sakana’s road to civil war.) Finally, for no real reason beyond the fact that One Million Years B.C. is set in prehistoric time, the volcano overlooking the Rock Tribe’s settlement erupts, interrupting the war and ushering in a resolution sequence that is inexplicably shot in sepia-tint monochrome, which seems to be trying to suggest that all of the troublemakers in the Rock Tribe are now gone, and that the remaining Rock People will henceforth be free to enjoy the fruits of the Beach Tribe’s social and technological advancement.

One Million Years B.C. makes an interesting contrast with its successor (but not sequel, per se) When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth. It is quite obvious that both films were produced by the same studio, as they have a very similar style to them, and in many ways, their stories echo each other. In both films, a lone representative from an extremely primitive, brutish, inland tribe comes into contact with the gentler, more advanced people of the seaside, falls in love-- perhaps even discovers love as we understand the term-- with a member of that more advanced society, is exiled from his/her adopted tribe, reconciles with them, and is ultimately forced to fight alongside his/her new companions against his/her own people, with frequent time-outs along the way for fighting with dinosaurs. And yet the differences between the two movies are such that it is immediately obvious, even to someone who does not know the release dates of either, which film is the prototype and which is the copy. One Million Years B.C. has an easygoing naturalness to it, an unaffected simplicity that is all the more noticeable in comparison to the forced epic grandeur of When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth. The former seems to have no ambition to be anything other than what it is-- an unpretentious little cavemen vs. dinosaurs flick-- while the latter is almost painfully self-conscious, its every scene twitching uneasily with a drive to outdo its predecessor. One Million Years B.C. is pretty dumb-- as any movie that pits anatomically modern humans against Mesozoic reptiles and Carboniferous-Period megabugs in the days of Homo erectus is bound to be-- but it is not bombastically dumb like its younger cousin. As such, it comes across, for all its shortcomings, as very much the better movie, though When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth is probably a little more fun. Then again, One Million Years B.C. definitely has the edge over its successor in the fur bikini department (if only by a little bit), and it has Ray Harryhausen. And seeing as I, at least, mostly watch these movies for the cool rubber dinosaurs and the cat-fighting cave-girls, that’s a major point in its favor.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact