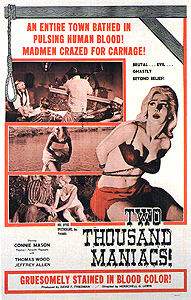

Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964) ***

Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964) ***

Fair warning: Two Thousand Maniacs! has a twist ending, and I’m going to spoil the shit out of it. I do so because the twist is integral to what elevates this movie so far above what would seem to be its natural level, making it stand out so starkly from the rest of Herschell Gordon Lewis’s mostly worthless output, and because there is thus no other way to explain why someone who has already subjected themselves to Blood Feast or The Wizard of Gore or any of the rest of that crap would stand to gain anything by giving Two Thousand Maniacs! a chance. Virtually alone among Lewis’s pioneering but uniformly awful gore-horror films, Two Thousand Maniacs! has something going on beneath the surface, and what gets revealed during those last few minutes is a crucial part of it.

110 miles north of Atlanta, a young man whom we will come to know as Rufus Tate (Gary Bakeman) stands perched in a tall tree by the side of the highway, peering at passing cars through a pair of binoculars. When he spies an isolated vehicle with Northern license plates— like that Ford from Illinois or that Mercury from… wait, who had blue text on mustard yellow in the mid-60’s? Pennsylvania, maybe? New Jersey?— he signals ahead to his friend, Lester McDonald (Ben Moore, of She Freak and Moonshine Mountain), who replaces the sign pointing Atlanta-ward with another announcing a detour down the little-traveled Route 202. A second detour sign a bit farther down directs the Northern drivers to turn right down the ill-maintained dirt track that leads, in about a quarter of a mile, to the little town of Pleasant Valley, South Carolina, population 2000. And if everything we’ve seen thus far (including that obvious reference to the maniacs of the title) wasn’t enough to convince us that nothing good could come of this, all the children roaming the streets of Pleasant Valley playing with miniature nooses certainly ought to be.

A total of six outsiders are taken in by Rufus and Lester’s subterfuge with the road signs. The white Ford contains married couples David (Michael Korb) and Beverly (Yvonne Gilbert) Wells and John (Jerome Eden, from Color Me Blood Red and Daughter of the Sun) and Bea (Nude on the Moon’s Shelby Livingston) Miller, on their way to a collective vacation in Florida. The red Mercury belongs to Terry Adams (Connie Mason, of Blood Feast and Black Mamba), who had been bound for Atlanta on who knows what business when she encountered Tom White (William Kerwin, from Barracuda and The Adventures of Lucky Pierre, acting under the pseudonym “Thomas Wood”), himself broken down en route to a teachers’ conference in the same city. All six are puzzled by the reception that greets them in Pleasant Valley— the cheering crowds, the frantically waving Confederate flags, the somehow aggressive effusiveness of Mayor Earl Buckman (Jeffrey Allen, of Something Weird and This Stuff’ll Kill Ya!) once the townspeople herd the outsiders to the center of the tiny commercial district. Nor do Buckman’s answers to their questions accomplish more than to raise a hundred new ones. Pleasant Valley is celebrating its centennial, and for some reason, that requires the presence of exactly six Northerners for the duration of the two-day festival. Terry, Tom, the Millers, and the Wellses will be the town’s honored guests, staying free of charge in the best hotel (which I rather suspect is also the only hotel), having all their needs provided for similarly free of charge, and apparently playing a pivotal role in a series of celebratory events the exact nature of which Buckman won’t go into just now. And as for the wayfarers’ protestations that they have places to go and things to do that are not consistent with being feted for two days in some tiny backwoods hickburg, well, Buckman simply won’t hear of it. He and his program directors (that is, Rufus and Lester) went to a lot of trouble to organize this festival, and the visitors wouldn’t want to disappoint the whole town now, would they?

Those of you who paid attention in history class will already have begun to suspect what’s going on here. A hundred years earlier (Two Thousand Maniacs! is explicitly set in April of 1965, roughly a year after the date of its release), the Civil War was nearing its conclusion, and the Union armies were marching across the heart of Dixie, burning and pillaging as they went. The Northern soldiers were especially ruthless in South Carolina, the first state to secede, and thus the one whose people were most responsible for the preceding four years of bloodshed, destruction, and misery. The ruin that General Sherman’s troops famously visited upon Georgia had been strategically motivated above all, a primitive, ground-based precursor to the bombing campaign against German and Japanese cities during World War II, but in South Carolina, it was payback— and the conduct of the invading army was correspondingly more savage. Now, on the hundredth anniversary of the Union forces’ arrival in Pleasant Valley, the townspeople are looking for a little vicarious payback of their own. Understand, however, that this is more than a politicized version of the typical Deep South back-country blood-feud. The soldiers who descended upon Pleasant Valley exterminated its inhabitants down to the last woman and child, and what the travelers from up north now face is the revenant of an entire town.

Yes, that’s right. When the Pleasant Valley Boys sing, in the main title theme, that the South is going to rise again, Herschell Gordon Lewis means that in an unusually literal sense. What makes Two Thousand Maniacs! so curious— makes it, in fact, one of the most subtextually rich horror films of the 1960’s— is the conflicted attitude it seems to represent toward that prospect. Herschell Gordon Lewis was a Northerner, born in Pittsburgh, educated in Chicago, and based in the latter city throughout his filmmaking career. Nevertheless, his earlier professional life (first as a college professor and later as advertising agent) had put him for years at a time in both Mississippi and Oklahoma, and when he retired from the movie business in the early 70’s, he migrated southward once again, this time to Florida. Lewis’s partner, David Friedman, meanwhile, was born in Birmingham, Alabama, but had also traveled extensively, settling in Chicago by the late 1950’s. So while Lewis and Friedman alike were Northern city-dwellers in 1964, both had some degree of Southern background and, or so it would appear, some affection for the region’s culture. Also, both men understood very well that it was in the South that their money was made; as Lewis himself would put it some 35 years later, “A typical audience member would live south of the Mason-Dixon line, would be between 25 and 45, would live in rural rather than urban circumstances, would probably be male, would not be highly educated, and would have a terrific number of prejudices.” Consider all that as you watch Two Thousand Maniacs!, and see the bizarre way the threads come together. The people of Pleasant Valley are condemned as maniacs in the very title, and in point of fact, that’s about the kindest word that could be justly applied to them. They’re also about the biggest collection of facile redneck stereotypes you’re going to see anywhere, a bunch of violent, greedy, ignorant, inbred halfwits from Mayor Buckman all the way down to the little boy whom the last survivors among the waylaid Yankees bamboozle into providing them with a means of escape. By any normal reckoning, they could scarcely be considered sympathetic characters, and yet we get to know them a great deal better than we do most of their victims, and Lewis often seems to be taking their side just a little. The undead villagers have a legitimate grievance, after all, even if their means of redressing it is backward, senseless, small-minded, and sadistic. Also, what little we learn of the Northerners seems calculated to prevent us from liking them very much. John and Bea Miller are dishonest, libidinous slimebags, whose marriage is defined on both sides by an unspoken contest to see how far each can push the openness of their infidelity without giving the other enough evidence to initiate divorce proceedings. David and Beverly Wells are the perfect clueless city-slickers, gullibly going along with anything and everything until it’s far too late for them to save themselves. Only Ted White and Terry Adams are portrayed in such a way that you might root for their survival, which is interesting in itself for all the cognitive dissonance it sets up. Throughout the movie, Lewis plays very skillfully to rural Southern anti-intellectualism, and to the South’s vision of itself as the aggrieved underdog, setting the conflict in terms that seem to say, “Yeah, look at that! Them Yankees ain’t so smart now, are they?” And yet it’s White— the schoolteacher— who overcomes the vengeful revenants of Pleasant Valley, and he does it by outwitting them. Intellect, in other words, carries the day after all, and the real underdogs are the captive travelers, outnumbered a thousand to one (at least in the final act) by undead psychopaths. To some extent, it’s clear that Lewis and Friedman simply understood the terrifically numerous prejudices of their primary audience, and had no qualms about exploiting them along the way to a conclusion affirming (albeit in a markedly provisional way) non-redneck values. But at the same time, the perfection of Two Thousand Maniacs! as a hillbilly revenge fantasy suggests that the fantasy had its allure for its creators as well.

This review is part of a much-belated B-Masters Cabal tribute to all the living dead things that we’ve been negelecting in favor of zombies all these years. Click the link below to read all that the Cabal finally came up with to say on the subject.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact