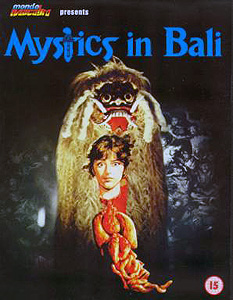

Mystics in Bali/Balinese Mystic/Leák (1981) **½

Mystics in Bali/Balinese Mystic/Leák (1981) **½

Like most geeky young males in the 1980’s, I dabbled a bit in role-playing games during my adolescence, and given the time period we’re talking about here, dabbling in role-playing games almost inevitably meant dabbling in Dungeons & Dragons. One of the Dungeons & Dragons monster books (it was the Fiend Folio, for those of you who are keeping score) included an entry for a creature called the penanggalan, a sort of vampire-witch thing with stats that would have made it very dangerous in the game. What really made the penanggalan special to me, however, was its appearance. When the sun set, the penanggalan would find a secluded spot and detach her head from her body; the head would then fly around in search of victims, trailing a huge mass of viscera beneath it! It was just about the most revolting— and consequently, just about the coolest— thing I’d ever heard of. So I expect you can imagine my subsequent pleasure, many years later, when I discovered that the penanggalan was not merely the product of some TSR employee having a particularly fruitful visit from the Icky Fairy back in 1981, but rather a legitimate figure of Indonesian folklore, and that the old legends went on to add the beautifully sick touch that the penanggalan has a particular taste for the blood of pregnant women and their unborn children. A more exciting discovery still would come a year or two later— there was an Indonesian movie industry, and said industry had produced a handful of horror films about penanggalans over the years.

Chances are you’ve figured out by now that Mystics in Bali is one such film. It represents the first foray into horror by an Indonesian director named Tjut Djalil, who subsequently became his country’s foremost specialist in “Western-style” horror. Do not make the mistake, however, of assuming that what the Indonesians consider “Western” in a horror movie bears more than the dimmest resemblance to anything actually originating in the West. Rather, it seems that what the Indonesians mean by “Western-style horror” is horror that makes extensive use of special effects, and that eschews the Bollywood-like tendency of traditional Indonesian cinema to juggle genres indiscriminately and to interrupt the action at regular intervals with annoying musical numbers. Mystics in Bali feels Western to the extent that it sticks to its business as a horror film; in every other respect, it is about as far from our filmmaking sensibility as anything you can imagine.

Mahendra (Yos Santo, from The Devil’s Sword and The Warrior and the Blind Swordsman) is a young and seemingly relatively Westernized Indonesian man. His new girlfriend, Catherine Keene (Illona Agathe Bastian— apparently not really an actress, but a German tourist whom Djalil’s casting director talked into accepting the part), is an aspiring writer from either Australia (in the original dialogue track) or the United States (in the English-language dub) with a pronounced interest in black magic. Cathy’s aim is to write a comprehensive book on all the major black magic traditions of the world, and her method for studying those traditions is arguably the most authoritative one there is— she finds herself a practitioner, and signs on as his or her apprentice. Having already been to Africa to bone up on Voodoo, Cathy has now come to Bali (one of the few parts of the Indonesian archipelago, incidentally, where Buddhists and pagans outnumber Muslims) to master Leák, Indonesia’s indigenous system of dark arts. But Cathy, being a foreigner, is naturally at a disadvantage when it comes to such things as trying to find a Balinese black magician who might be willing to teach her, so she turns to Mahendra for assistance.

This is an odd bit of business, so it seems worthwhile to look at it in some detail. Honestly, I’m not at all clear on just how deeply Mahendra buys into the validity of Leák. On the one hand, he consistently tells Cathy that Leák is nothing to trifle with, and that it is in fact the most powerful form of witchcraft known to man. He also, as we shall see later, is part of a family with an extremely strong background in white magic, so one would assume that he’d be likely to accept the reality of both Leák and its antithesis. However, his behavior makes no sense at all unless he’s no more a believer than Cathy is, and looks at Leák solely as a matter of intellectual curiosity. For having met this girl who wants to delve as deeply as possible into the blackest art of them all, Mahendra seemingly has no qualms about asking around until he’s found a line on a Leák sorceress. Surely a man who took wizardry seriously would never consent to do such a thing!

Regardless, a few days after Hendra and Cathy discuss what brings her to Bali, they travel into the countryside to what seems to be a cemetery, which is to serve as their rendezvous point with the sorceress (Queen of Black Magic’s Sofia W. D.). The witch keeps her appointment, slinking out of the woods sometime around midnight— preceded, as is only proper for such a personage, by a sudden and intense thunderstorm— and the two women negotiate the terms of Cathy’s apprenticeship. Once the arrangements have been made to everybody’s satisfaction, the witch underscores her good faith by offering to seal the deal in the Western manner, with a handshake. But as the hideous old crone wanders off on her way afterward (with a cackle that’s a dead ringer for the one that opens the Surfaris’ classic instrumental, “Wipeout”), Cathy notices that she’s left her taloned forearm behind in the girl’s hand. Cathy, understandably revolted, immediately drops the severed member onto the ground, at which point it comes alive and skitters off after its owner. Any doubt Cathy and Hendra might have had about the reality of Leák certainly ought to have been dispelled by that! But nevertheless, both young nitwits go right ahead with the plan as if nothing were even the slightest bit amiss.

The next night, they meet again with the sorceress, this time to make offerings to her— a handful of gems and an enormous quantity of blood for her to drink. The old witch had warned Cathy that she would appear in a different guise each time they met, and she’s as good as her word. Though we don’t get to see much of her this time around, whatever body the witch is using tonight has a forked, warty, prehensile tongue nearly 30 feet long, which she uses not only to take the gems from Cathy’s hand and to slurp down a good five liters of blood (am I the only one who is wondering uneasily just where Cathy got that from?), but to scratch some kind of Leák tattoo into the skin of the girl’s right thigh. This is to provide a channel whereby the witch’s magic might flow into her apprentice; the tattoo is sited on the upper thigh so that no one who is not privy to Cathy’s arrangement with the witch will be able to see it. I can only conclude that, having lived since 1968 under Suharto’s puritanical dictatorship, the witch is unaware of miniskirts, hot-pants, and bikinis. Regardless, each night hence, Cathy and her tutor (the witch banishes Hendra from future rendezvous) will get together in the latter’s favorite graveyard to cackle maniacally, strike strange, insectile poses, and transform themselves into such unpopular animals as pigs and pythons.

So how does Mahendra pass the time now that he’s no longer allowed to sit in on his girlfriend’s witchcraft lessons? Why, he sneaks out of the house to spy on them, of course! What Hendra sees is enough to get him worried about Cathy, so he pays a visit to his uncle, Machesse (W. D. Mochtar, of The Headless Terror and Satan’s Slave), a good wizard who is also the head of some sort of village council. Machesse takes a surprisingly lenient line on his nephew leading unsuspecting foreign girls into Leák damnation, but maybe that’s because he knows the sacred mantras that can render a witch powerless. Of course, that line of reason takes no account of the youth’s character. When Machesse teaches the mantras to Mahendra, you might think it means that Hendra is going to use them to disentangle Cathy from the witch’s influence, but you’d be way wrong. Instead, our hero continues to demonstrate his qualifications to head up Indonesia’s Olympic ass-sitting team, even when the Leák sorceress gets her hooks so deeply into Cathy as to transform her into a penanggalan slave! The reason the old witch wants a penanggalan slave is that despite her enormous power, she is still mortal. But if she can ingest the blood of three unborn children, she will regain her youth and acquire eternal life, and apparently vicarious ingestion via a remote-control penanggalan works just as well as drinking the blood the old-fashioned way. Hendra, pretty well useless to begin with, now takes a job as a sailor, meaning that he won’t even be in town for several days. Luckily, there’s an attractive young girl (probably Debbie Cynthia Dewi, of Five Deadly Angels) who has been following him and Cathy around at a discreet distance, and she is sufficiently with it to see what Cathy is now up to, and get word back to Uncle Machesse. Machesse, using occult knowledge passed down to him from his uncle, is able to prevent Cathy from accomplishing the witch’s purpose, but not to save her from evil undeath; it proves necessary to kill the detachable-headed girl. Unfortunately, unless Cathy’s burial is performed in a certain highly specific way and her grave prayed over for three successive nights, she will be able to rise again in even more powerful form— and that, naturally, would suit her mistress just fine. Hendra’s ship comes back just in time for him to help keep the vigil, and he is thus on hand when the Leák sorceress shows up to pick a fight. Over the course of this battle, we will discover that the girl who’s been snooping around all movie long is really Hendra’s jealous ex, Maya, and see the day saved by a character who has had nothing whatever to do with the story up to now. Ige Oka, the bath-towel-clad sorcerer who appears at the last minute to administer the coup de smackdown to the Leák queen and the resurrected Cathy, is none other than Hendra’s uncle’s uncle, the one who got the family involved in the magic business in the first place!

Mystics in Bali is one of the very weirdest movies I’ve ever seen, no two ways about it. Most obviously, it draws its subject matter from a body of legendry with which most Westerners will be totally unfamiliar, but because it was made primarily for an Indonesian audience, the filmmakers understandably wasted no time on exposition. After all, not only would virtually everyone in the intended audience know perfectly well what the ground rules are for penanggalans, Leák wizards, and the rest, but outside of Indonesia’s four major cities, the majority of the people watching this movie would probably believe in the literal reality of all those things. The side-effect, of course, is that non-Indonesians are pretty much left to hang on and roll with it, gleaning whatever they can from context clues and filling in the gaps from intuition. It will be a hindrance for some and a selling point for others, but rarely will more than two successive scenes go by without a major “What the fuck?!?!” moment. Some of them are brilliant, like the image of a pregnant woman’s belly deflating as Cathy goes to work on her. Others are stunningly silly, like when the sorceress turns herself into a pig-woman to battle Machesse. And sometimes, it’s hard to know whether to laugh or retch, as in the incredible scene following Cathy’s night out as a were-python, in which she is overcome by nausea after resuming human form, and flees into the bathroom to vomit up a belly-full of live mice.

But there is a deeper form of weirdness on display in Mystics in Bali than any mere matter of unfamiliar subject matter. The film exhibits an almost total lack of concern for conventional narrative structure as we in the West understand it. Maya, for example, gets her formal introduction only after receiving a mortal wound in the climactic battle. Nothing Machesse or Hendra says about old Ige Oka even hints at the possibility that he might still be alive, rendering his sudden appearance at the end doubly disorienting. Time transitions are extremely jarring throughout, none more so than the interval between Cathy’s first and second meetings with the sorceress. Were it not for an easily missed line of dialogue, there would be no certain way of telling that any time had passed at all, let alone a full 24 hours. What’s interesting about all this is that it seems to be a matter of deliberate choice, or at the very least the product of adherence to a set of conventions that is utterly at variance from our own. Tjut Djalil gives the impression of being not a bad director, but a pretty damned good one who happens to be operating according to a completely alien notion of storytelling. His approach to Mystics in Bali is baffling and strange, but there unquestionably is some sort of logic behind it— it’s just going to take a good, long while (and probably exposure to quite a few more Indonesian movies) before I get a fix on what that logic is.

Thanks to Dr. Freex for supplying me with my copy of this film. Only took me a year to get around to watching it…

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact