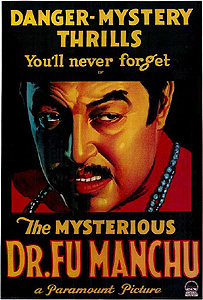

The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu (1929) **

The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu (1929) **

The origins of most entertainment genres are at least somewhat vague and nebulous, partaking of too many influences for the questions, “Why here? Why now? Why in this particular form?” to be given any one satisfactory answer. That is not the case, however, with the Yellow Peril stories of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Their origins are perfectly concrete, although they stem from events that are surprisingly little remembered today on this side of the globe.

Cast your mind back for a moment to the middle of the 19th century. The age of colonialism was in full swing, with the nations of the newly industrialized West turning the previous decades’ enormous advances in the sciences of agriculture, manufacturing, transportation, and mechanical engineering into an unanswerable military advantage, and exploiting that in turn to subjugate as much of the rest of the world as they could reach. The stone-agers of the Americas had long since been beaten down, and the native inhabitants of Subsaharan Africa were so helpless to resist the feeding frenzy of European conquest that even Belgium was able to carve out a substantial empire spreading out from the banks of the Congo River. The islands of Oceania fell like dominos before the acquisitiveness of Britain, France, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, and later Germany and the United States of America. Rugged and sparsely populated Central Asia was the site of a decades-long land-grabbing duel between Britain and Russia. And of the greatest significance, even the ancient and apparently powerful civilizations of Asia and the Middle East— Persia, India, China, the Ottoman Empire— found themselves in the novel and unwelcome position of having to fight for their very survival against rivals which, only a century and a half before, they had either never heard of or believed to be of little account. For those once-great empires, the advent of Western invaders who not only considered themselves to be the rightful and natural rulers of the Earth, but had the military might to back up their arrogant ambitions, represented nothing less than the complete inversion of the way the world had worked since time immemorial.

But then, between 1894 and 1905, the rules of the geopolitical game changed a second time, and it was the West’s turn for a rude awakening. Western observers had always reckoned China and Japan to be too powerful to conquer outright, and so colonial incursions into those countries instead took the form of leases on port cities and treaties guaranteeing trade advantages and legal immunities for the citizens of European states. Nevertheless, the men who opened the markets of East Asia to trade with the West knew that they dealt from a position of strength, and believed that their governments could force any concession they desired— conquest might have been out of the question, but it was common knowledge that not even the greatest power in Asia could prevail over a modern Western military. The Asians, for their part, must have agreed, for beginning in the 1860’s, China and Japan both undertook to Westernize their armies and navies to one extent or another. In China, the reforms were little more than cosmetic. The Chinese bought European rifles and artillery, and ordered modern warships constructed in German and British dockyards, but training in the use of these new tools was haphazard, and military organization remained positively medieval. The Japanese were more serious. Emboldened by the certainty that their new boy emperor would be too weak to oppose them even if he disagreed with their program, the nobility and military leadership of Japan promulgated a European-style constitution (modeled on that devised for Prussia by Otto Von Bismarck), and brought in European advisors to rebuild Japan’s armed forces from the ground up. The army, like the constitution, would be of Prussian character, while the navy would mimic that of Great Britain— Japan’s reformers had obviously paid close attention to recent events in the other hemisphere. By the 1890’s, the Meiji Restoration (as the political, social, and military reforms in Japan were collectively known) had taken firm enough root that the island nation felt sufficiently confident to challenge China for the leadership of East Asia, and as it became increasingly obvious that the Chinese lacked either the strength or the will to oppose Russian inroads to Manchuria and Korea, the pitch of that challenge grew sharper and sharper. When war broke out in 1894, nearly all observers outside of Japan believed that China would emerge victorious, but that’s not how it happened. Indeed, the Chinese folded so rapidly and amid such abject disorder that even the Japanese were shocked at their success. Even more shocking was the outcome of the sequel, when the escalating Russo-Japanese rivalry finally led to war between those two countries in 1904. Russia fared a little better and lasted a little longer than China did, but the end result was a rout no less spectacular. With its army pinned down and starving to death in Manchuria, two thirds of its navy interned in neutral ports or rusting at the bottom of the sea, and its first Communist revolution threatening to extinguish the Romanov dynasty back home, Russia had no choice but to sue for peace and trust in American mediation at the conference table to minimize the humiliation of the final settlement. For the first time since the 17th-century apogee of Ottoman military strength, one of the great Western powers had been roundly defeated in war by a nation of non-whites. And in between the two Japanese triumphs, the Chinese managed to do a little ass-kicking of their own in the Boxer Rebellion. Though the revolt was a disastrous failure, the spectacle of the supposedly placid and tractable Chinese peasantry rising up in a bid to expel all foreigners from their land threw a scare into many in the West, especially in Great Britain.

It was against this backdrop that the notion of a “Yellow Peril” first emerged. The Russians, understandably, were the first to take up the warning cry, but the earliest known artwork dramatizing the idea (assuming such a crude piece of propaganda merits being called “art”) was instead produced in Germany for Russian consumption. While the Sino-Japanese war was raging, Kaiser Wilhelm II sent his cousin, Czar Nicholas II, a huge painting in which figures representing all the great powers of the West were menaced by dense thunderheads surmounted by a flaming image of Buddha— this tawdry canvas was actually entitled The Yellow Peril! Russia’s miserable performance in the war against Japan gave the idea much greater currency, and within a few years, some variation on the theme could be heard in any Western nation with interests in the Far East. While Western governments scrambled for workable responses to Japanese ascendancy (the British were the most creative, co-opting the perceived threat by signing a treaty of alliance with Japan— Britain’s first formal military pact since the Napoleonic Wars), the popular media went predictably apeshit. In addition to the usual overheated newspaper editorials, the three decades after 1905 saw the rise of a new genre of pulp fiction, in which sinister Oriental geniuses schemed to avenge themselves upon the white race, typically matching their wits against those of a Western hero detective on the Sherlock Holmes model. The most significant author to work in this field was the Englishman Sax Rohmer. Beginning in 1912 with “The Story Teller,” Rohmer wrote innumerable stories and novels detailing the career of a Chinese arch-criminal called Fu Manchu; the last of the series, Emperor Fu Manchu, appeared as late as 1959. The books were hugely successful, and for a while at least, they made Rohmer a rich and famous man.

And that, at last, brings us to the movies. Whenever a pulp property moved as many units as the Fu Manchu stories did, the film industry could be counted upon to come on the run. The cashing in began as early as 1914, when New York’s Feature Photoplay Company shamelessly ripped off some tales of Rohmer’s arch-villain for the serial The Mysterious Mr. Wu Chung Foo, never giving the author any credit for the pilfered plotlines or paying him a single dime in royalties. Fu Manchu made his legitimate screen debut nine years later in Britain with another pair of serials, The Mystery of Dr. Fu Manchu and The Further Mysteries of Fu Manchu. The jump to Hollywood and full feature length finally occurred in 1929, when Paramount brought forth The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu, the initial installment in what would become a three-picture series. The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu was not merely Hollywood’s first take on the Devil Doctor, or the first feature dedicated to the character, but the first Fu Manchu talkie as well.

As is only to be expected, the opening scene takes place during the Boxer Rebellion. As the rebels lay siege to the British legation in Peking, a man named Eltham (Chappell Dossett) prepares to smuggle his little daughter to safety. Eltham is close friends with a Chinese doctor named Fu Manchu (Warner Oland, from The Drums of Jeopardy and Werewolf of London), and Fu has agreed to look after the girl either until Eltham is able to get away himself or permanently in the event that Eltham should die in the fighting. Fu’s servant, Li Po (Noble Johnson, from The Thief of Bagdad and The Mad Doctor of Market Street), arrives just in time, carrying Lia Eltham out of the embattled legation in a big ceramic water jug. Nevertheless, matters do not go according to plan. A multinational army consisting of British, French, German, and American troops arrives on the scene minutes after Li Po brings Lia to his master’s villa, and that army’s artillery corps is none too picky about where it directs its fire. A shell plunges straight into Fu Manchu’s living room, killing the doctor’s entire family. Mad with grief, Fu concludes that the Boxers had the right idea after all— the white race really is nothing more than a horde of treacherous, murdering barbarians. From that day forward, Fu vows revenge against the killers of his wife and children through three generations, and swears further to use Lia as the instrument of his vengeance.

Some fifteen years later, in London, Dr. James Petrie (Neil Hamilton, of The Cat Creeps and The Devil’s Hand) has a strange encounter with a girl in her late teens (Jean Arthur). He finds the girl wandering through the misty night as if in a trance, and when he snaps her out of it by tripping over her foot and spraining her ankle (Petrie is not exactly the suavest guy in the world), she says that she is unable to remember what she was up to or where she had been going. Petrie offers to take her home, but the girl unexpectedly goes off in a different carriage while the doctor attempts to hail a cab.

The strange girl might not have known where she was going, but Petrie’s destination is the home of his father, Sir John Petrie (Claude King, from London After Midnight and The Mystery of the Wax Museum), where he plans on celebrating his grandfather’s 80th birthday. (Incidentally, check out Sir John’s secretary, Sylvester Wadsworth [The Return of the Vampire’s William Austin]. Apparently casting aspersions on Chinamen wasn’t enough— we’ve got to have a comic-relief poofter in here, too!) The birthday boy is none other than General Petrie (Charles A. Stevenson), hero of the Boxer Rebellion, so it is surely no coincidence when one of the servants brings the general an envelope containing a small painting of a Chinese dragon exactly like the one from the big silk tapestry that once adorned Fu Manchu’s living room. No sooner have the Petries begun puzzling over the dragon card than they are visited by Inspector Nayland Smith (Bride of Frankenstein’s O. P. Heggie) of Scotland Yard. Smith has come to warn General Petrie that his life is in great danger; all of the other generals with whom he shared command of the unit that saved the British legation in Peking have died during the preceding months, poisoned together with their whole families. What’s more, each of the dead men received cards identical to the one Petrie just got on the days of their demise. General Petrie scoffs at the notion that he has been marked for death, but then he pops open his tin of pipe tobacco, and is overcome by a cloud of lethal gas! If Smith and the two younger Petries had been standing just a little bit closer to the general at the time, they would certainly have shared his fate. Luckily the inspector did not come alone, and one of his men spots a prowler sneaking off of the Petrie mansion’s grounds. The second cop trails the prowler all the way to Limehouse— London’s Chinatown— where he disappears into a tavern called Singapore Charlie’s. The Scotland Yard man is unable to continue the chase, however, for he is struck down by a poisoned blowgun dart, fired from a window in the flat above the tavern. He is barely able to phone in his observations to Inspector Smith before he dies.

The next evening, Smith pays a visit to Singapore Charlie’s, in company with James Petrie and a policeman named Trent (Donald MacKenzie); all three men are posing as drunken sailors. While sitting at the bar, Trent notices someone watching from behind a large, square peephole in the far wall of the tavern, and quickly discovers that said wall contains a hidden door to the alley behind the pub. Smith and the others rush out in the hope of catching whomever was spying on them, but they get lost and separated in Limehouse’s warren of back alleys. Petrie gets the most lost of all, blundering through another back door into the bedroom of the very girl whom he had met on the street the night before. Once he’s managed to convince her that he isn’t a burglar, she introduces herself as Lia Eltham— aha! I knew it!— and suggests that her guardian, the celebrated physician Dr. Fu Manchu, might be able to help him get to the bottom of his grandfather’s murder. After all, the killer apparently operates out of Limehouse, and there’s nothing about Limehouse that Dr. Fu doesn’t know. I’m sure you can imagine the mayhem that follows when Smith and the Petries entrust themselves to a man who is really their sworn enemy, especially if I tell you that Fu possesses not only a thuggish henchman who’s a crack shot with a blowgun, but also hypnotic powers that enable him to use Lia as his remote-control slave.

As one would expect of a talkie from 1929, The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu is extremely creaky and slow-moving, hampered by stilted dialogue and rather abysmal acting. Any movie in which the silent-as-usual Noble Johnson puts in the most effective performance is in serious trouble. In those places where it works anyway, it gets by on an unusually sympathetic reading of the bad guy’s motivation and a surprising willingness to give him the upper hand. In the first place, notice that Fu begins the film as a supporter of the West, embarking on his private race-war only after his wife and children become collateral casualties of the European counterattack against the Boxers. In the second, this movie presents for once a story about an evil genius who really does seem to be as dangerous as everybody says. Fu Manchu has the advantage here until the last five minutes of the film, effortlessly making a monkey out of Nayland Smith until a miscalculation he made way back in 1900 comes back to bite him on the ass. That fact plays up a fascinating characteristic of the Yellow Peril genre that probably accounts for why I find movies like this one a bit less offensive than equally racist pictures of the same vintage which direct their stereotyping against black people. In a sense, Yellow Peril stories pay their Oriental villains (and by extension, the race they represent) a sort of back-handed compliment. While racist stereotypes about blacks typically paint them as too lazy and stupid to be dangerous except through a supposed predilection for criminality or an insatiable sexual appetite for white women, the Yellow Peril theory has it that Asians are a threat to white dominance because they’re the only people in the world who might be able to beat us at our own game. To view the people of East and Southeast Asia as a tribe of diabolical geniuses is obviously pernicious and unfair, but a diabolical genius is still a genius at the end of the day. Consequently, it seems plain to me that at the core of Yellow Peril racism, there lies a kernel of, if not respect precisely, then at least a willingness to credit Asians with a substantial degree of talent and competence. White supremacists never sound so secretly unsure of themselves as when they’re asserting the inferiority of the Oriental.

Of course, there’s one major problem with looking at The Mysterious Dr. Fu Manchu from that perspective— the first thing any slightly observant viewer will notice about this movie is that there aren’t any actual Asians in it!!!! Fu himself is played by Warner Oland, a Swede. His maid, Fai Lu, is played by Evelyn Selbie, a Caucasian bit player with a long resumé of inconsequential acting gigs. And in the most baffling casting gambit of all, the henchman Li Po is played by Noble Johnson, a black character actor who spent much of his career performing in white- or yellowface! What the hell is going on here?!

It seems to me that there are two possible explanations, one relatively innocent and the other openly malicious. Probably the true story is some combination of both. First of all, it’s worth pointing out that there were indeed a substantial number of Asian actors working in Hollywood during the silent era. For example, although the Charlie Chan talkies of the 30’s and 40’s all featured a white actor in the title role (in fact, most of them featured Warner Oland), their silent predecessors starred real Orientals like George Kuwa and Kamiyama Sojin. But then around the turn of the 1930’s came the beginning of a plague of fake Asians that would not completely run its course until some 40 years later. Obviously something happened around 1930 to make the casting of Asians in major roles no longer acceptable in Hollywood. Part of it may simply have been the demands of sound. Plenty of white silent stars had their careers derailed at least temporarily by a language barrier or a foreign accent. Consider Conrad Veidt, who thought his prospects so poor that he went back to his homeland for a few years after the talkies took over— can you imagine how grim the future has to look before it makes sense for an incorrigible anti-authoritarian troublemaker with a Jewish wife to abandon Los Angeles for 1930’s Germany?!?! Looked at in that light, it comes as no shock that the few Asian actors to remain in Hollywood during the 1930’s (Anna May Wong, for instance) had mostly been born and raised in the United States. But at the same time, it must be borne in mind that anti-Asian— and especially anti-Japanese— sentiment was on a rapid rise in America after about 1928. The rivalry between Japan and the US was intensifying again after the short relaxation that accompanied the Washington Treaty on Naval Disarmament, for one thing, and for another, the onset of the Great Depression at the end of 1929 triggered exactly the sort of churlish outburst of anti-immigrant labor protectionism that always follows a big economic downturn. Most of America’s Asian immigrants lived in California during the 1930’s, and it doesn’t take much intellectual exertion to imagine the casting of whites in yellowface as Hollywood’s Depression-era version of “Buy American!” What does require exertion is trying to figure out how it could still seem okay for Christopher Lee to be playing Fu Manchu in 1969...

This review is part of what might be the most tasteless B-Masters Cabal roundtable yet, a concerted look at the truly inscrutable (and in no sense honorable) Hollywood tradition of sticking fake eyelids on a white guy and then casting him as an Asian. Click on the banner below to see whether my colleagues had any more luck making sense of it than I did.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact