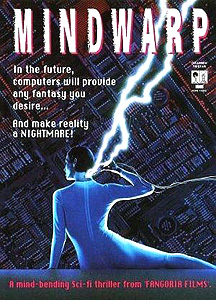

Mindwarp (1990) **½

Mindwarp (1990) **½

Fangoria’s is not a logo I like to see in a movie’s credits. That magazine’s fascination with special effects above all else tends to encourage exactly the wrong approach to small-scale filmmaking, and productions in which Fangoria had a hand frequently give the impression that their creators had no interest in anything except proving that lack of money need not be an obstacle to dazzling an audience with elaborate gore. Mindwarp is at least somewhat better than Fangoria’s overall track record would lead one to anticipate, however. The most likely explanation for this is that it not a horror movie, but rather a sci-fi film, meaning that director Steve Barnett and writers John Brancato, Henry Dominic, and Michael Ferris were just about obligated to have more up their sleeves than a bunch of severed limbs. What they’ve given us is an 80’s-style post-apocalypse film with an unexpected hint of The Matrix, most of a decade before there was such a thing as The Matrix to hint at.

Humanity has, as usual, destroyed itself in a nuclear war. A certain percentage of the population (just how much is never made clear) escaped the apocalypse by going underground, where they now live in a simulated reality provided by the Infinisynth system. Basically, the people of the Inworld spend their lives jacked into a vast computer network, dreaming whatever existence it pleases them to invent; they awaken only to fulfill the biological requirements of their bodies. There are, however, a few Inworlders who are not satisfied with simulations. A twenty-ish girl named Judy (Marta Alicia), for instance, wants some real reality in her life, and she spends most of her time while jacked in sparring with the System Operator over her desire to experience something that was not concocted by a machine. Judy’s mother (Mary Becker) doesn’t understand her yearnings any more than the System Operator does, and the girl’s increasingly strident efforts to make her mom see the light lead to a horrible mishap. Judy somehow manages to hijack her mother’s dream of being a successful opera singer, and turn it sour. She thinks the result will be to jolt mom awake, but the shock kills her instead. Realizing that Judy has become a menace to society, the System Operator sentences her to receive exactly what she wants. A group of soldiers burst into the room she shares (or rather, shared) with her mother, zip her up in an enormous, white sack, and dump her on the surface.

The surface sucks. It’s cold, it’s ugly, it’s barren, and there are shriveled-up, crucified mummies hanging all over the place. Oh— and there are also sinkholes. Scarcely has Judy had a chance to look around than she sticks her foot into one, and begins falling slowly into the collapsing sand. Luckily for her, there are a couple of fur-clad men driving around the frigid wastes on a farm tractor, and they spot the struggling girl in time to toss her a rope and haul her out of peril. Then again, since they’re hauling her into graver peril still, maybe this isn’t such a lucky break after all. Judy’s “rescuers” are in fact mutated cannibals, and unless I’ve missed my guess, being carved into cutlets is the nicest thing that could happen to her in their clutches. But then another fur-swaddled figure appears, and proceeds to mow down the mutants with his crossbow and broadsword. Judy is understandably suspicious of the interloper’s intentions (fool me once, and all that), but this time she really has been rescued. Underneath all the ragged furs is a perfectly normal man who calls himself Stover (Bruce Campbell, from The Man with the Screaming Brain and Sundown: The Vampire in Retreat), and his first words to Judy are, “You’d better cover up, or you’ll die out here.”

Stover takes Judy in at his hut, and springs into action in his secret identity as Exposition Man (the tireless defender of Truth, Justice, and Narrative Cohesion). Stover turns out to be the last known survivor of a tribe of humans who were left behind on the Earth’s surface after the Final War, but who were able somehow to prevent themselves from sinking into savagery and mutation. Meanwhile, the Crawlers— those mutants who tried to carry Judy off— represent the bulk of what’s left of humanity. They live underground in the landfills, mining the garbage of the 20th century and subsisting by eating their own dead. They also used to capture Stover’s people when they could, along with robbing the human Outworlders’ graves— that’s why Stover’s people took to hanging their dead from the tops of twenty-foot crosses. All Stover knows about Inworld comes from the garbled legends passed down by his ancestors, and of that, all he particularly cares about is the fact that his people were abandoned. He’ll let ancestral bygones be ancestral bygones, though, if it means he can have Judy for companionship, for until she showed up, he had just about convinced himself that he was the last human on Earth.

The couple’s relative bliss is short-lived, however, for the Crawlers have finally discovered Stover’s lair. Tunneling under and around the hut, they break in one night and abduct both humans. Stover is put to work in the landfill’s junk mines, but the Crawlers have a very different fate in mind for Judy. The Crawlers, as you might have guessed, are congenitally sterile for the most part, and their leader, the Seer (Angus Scrimm, from Chopping Mall and Vampirella), has instituted a breeding program based upon kidnapping unmutated Outworlders. In a hidden chamber adjoining his quarters, the Seer has a whole nursery full of women bearing fetuses of varying degrees of monstrousness, watched over by a spiteful (and presumably sterile) shrew named Cornelia (Trapped Alive’s Elizabeth Kent) and her adolescent handmaiden, Claude (Wendy Sandow). Judy, having spent her whole life insulated from the contamination of Outworld, is obviously the ultimate prize for the Seer, who hopes to use a combination of eugenics and a grotesque religion of his own devising to elevate the Crawlers to something more closely approaching the level of their pre-apocalyptic ancestors. Understandably, she herself is not terribly keen on the idea. Stover, too, is not happy with his place in the Seer’s plan, and he, like Judy, can be counted upon to spend every available moment looking for avenues of escape. There’s one major complication, however. Once she gets a chance to see him without his leather hood, Judy realizes that she and the Seer used to know each other very well indeed…

Mindwarp’s biggest problem is the acting. Bruce Campbell and Angus Scrimm are their usual professional selves, but everybody else in the cast is absolutely useless. Marta Alicia is too wooden and lethargic for a leading role like this one, Elizabeth Kent doesn’t so much chew the scenery as devour it in raw and bloody hunks, and Wendy Sandow is acceptable only because she has (unless I missed another one under the whistle of my teakettle) exactly one word of dialogue. A couple of the extras playing the Crawlers, meanwhile, can’t even deliver a grunt or a squeal believably. The overall failure of the acting is doubly unfortunate because there’s a lot going on in Mindwarp that deserved a more competent treatment. The movie represents a surprisingly imaginative handling of a premise that otherwise seemed to be completely played out by the turn of the 90’s, and the physical elements of the production are mostly very effective. There is an attention to detail visible in such things as the (literally) bloodthirsty faith of the Crawlers or the true purpose behind the crucified mummies at the edge of the Dead Lands that one rarely sees in post-apocalypse movies of this era, and I was reminded throughout (in a good way) of DEFCON-4, another sadly botched attempt to do something in the genre a bit different from the usual ritualistic Road Warrior plagiarism. Most importantly, Mindwarp gives the notion of a computer-simulated reality a spin that I don’t think I’ve seen anywhere else. Though it starts on the expected note of revolt against artificiality, the movie seems increasingly to be arguing that there are times when reality is so top-to-bottom horrible that a person would have to be insane to prefer it to a carefully crafted system of comfortable lies. And while that sure as hell isn’t a philosophy I can get behind, I have to give Mindwarp’s creators credit for individuality in making the argument, even if they didn’t necessarily set out to do so. It was the last thing in the world that I was expecting, and it has the collateral effect of redeeming a cop-out ending by making it follow logically from the rest of the story.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact