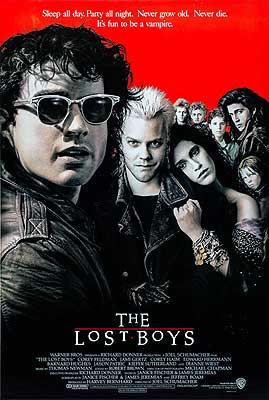

The Lost Boys (1987) **½

The Lost Boys (1987) **½

It’s weird that a picture so obviously intended to eulogize a dying genre should bring it roaring back to life instead, but that’s exactly what happened to vampire movies in the wake of Fright Night. So far as I can recall, the entire 1980’s up to that point had produced but a single vampire film of any consequence, 1983’s The Hunger. Peter Vincent would have felt right at home in the post-Fright Night horror movie ecology, though. In addition to the inevitable Fright Night, Part II, the undead ran rampant in Vamp, Near Dark, The Lost Boys, To Die For, Graveyard Shift, The Understudy: Graveyard Shift II, and even Lifeforce in a crooked sort of way. Bloodsucking stayed big into the 90’s, too, as the pro- and anti-Anne Rice factions battled for supremacy. Next came Joss Whedon, then Stephanie Meyer, and now a lot of us are starting to wish the genre would get back into its fucking coffin for a few years. But returning to the mid-80’s, it’s remarkable how little it took to make vampires cool again. Most of the movies that followed Fright Night drew mainly on its esthetic sensibility. That is, they learned how to make the undead look like refugees from MTV. Don’t knock it, though— esthetics matter a lot for a genre struggling to maintain relevance, whatever people might think of those esthetics 30 years down the line. More genuinely pernicious was the other lesson subsequent filmmakers learned from Fright Night, to lower the stakes by making vampirism a more easily reversible condition than it had been previously. The Lost Boys in particular took both sets of pointers very strongly to heart, but it also follows the example of Fright Night in a way that its competitors did not. It too treats vampirism as a metaphor for homosexuality, although it’s at great pains to pretend that it’s doing no such thing.

Lucy (Dianne Wiest, of Edward Scissorhands) is the newly divorced mother of two teenaged boys. As soon as the last of the papers are signed, she packs up her sons, Michael (Jason Patric, from Solarbabies and Frankenstein Unbound) and Sam (Corey Haim, of Watchers and Silver Bullet), and decamps to the little Southern California beach community of Santa Carla, the home of her somewhat batty father (Barnard Hughes, from Sisters and Tron). On the way into town, Sam observes with legitimate alarm the extra line that some graffiti artist has added to the big “Welcome to Santa Carla” billboard: “The Murder Capital of the World.” As a practical matter, though, Sam is more horrified to discover that Grandpa doesn’t own a television set.

Santa Carla being primarily a resort town, most of the business there is entertainment-oriented in one way or another. Thus it is that Lucy finds herself in the incongruously menial position of working as a clerk in a video rental shop. On the other hand, maybe Lucy stands to gain something better than money from the gig, since Max (Edward Hermann, of The Electric Grandmother and The Shaft), the owner of the store, is single and seems to like her. The same shopping and entertainment complex (it doesn’t seem to be quite a mall in the usual sense) also includes a comic book store, which is where Sam ends up spending most of his spare time as he gets settled in. The proprietors there have two sons about his age— Edgar (Corey Feldman, from Bordello of Blood and Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter) and Alan (Jamison Newlander, of Young Blood: Evil Intentions and The Blob) Frog— who quickly become the closest thing to friends that Sam has in his new town. The Frog brothers are weirdly intense, and have an unnerving habit of pushing vampire comics on Sam even after he tells them that he has no interest in that horror stuff. Their obsessive behavior makes him feel almost as if he’s being initiated into a cult without knowing any of its rites or doctrine. Not that he lets that stop him from hanging out with the two freakoids, you understand.

Meanwhile, Michael too is establishing a new social circle. It begins when the Beefcake Saxophone Guy (You remember him, right? He was all over the mid-1980’s.) puts on a show at Santa Carla’s concert pavilion, and Michael catches sight of a girl named Star (Jami Gertz, who was also in Solarbabies) on the margins of the crowd. Michael charges off to flirt with her, but it turns out that she’s already spoken for. Moreover, her boyfriend is David (Kiefer Sutherland, from Flatliners and Dark City), leader of the turbo-mulletted metal-punk-biker dudes whom we’ve seen off and on menacing people at all of the local teen hangouts. Most people would let that be the end of it, but not Michael— and this is where The Lost Boys starts to turn gay. Pay close attention to the look David shoots Michael at their first meeting, as he peremptorily summons Star onto the back of his motorcycle. That isn’t “Hey, skuzz— take your hands off my chick before I feed them to you.” No, it’s unmistakably “Hey, hot stuff— you know you want a piece of this.” And while the circumstances permit us to read the expression of longing with which Michael answers that look as referring to Star, the ensuing action makes ever so much more sense if we interpret it as a deeply closeted romance between the two boys.

David and his gang are vampires, you see, and Michael’s side of the story from here on out is a clear case of seduction in the textbook post-70’s vampire movie style. It may be Star who brings them together, but it’s Michael that David really wants to turn. As the title suggests, David becomes a sort of diabolical Peter Pan figure, wooing Michael with the prospect of unnaturally preserved youth, imperviousness to the consequences of risk-taking or thrill-seeking, and the indefinite suspension of adult responsibility. And really, what rebellious teenager wouldn’t want what David is offering— especially when it doesn’t even require being bitten? Yeah, that’s how The Lost Boys keeps the relationship between David and Michael looking at least nominally platonic. Its vampire lore posits that the bite of the undead merely kills; it’s the drinking of blood (presumably blood from a vampire, although that’s never stated explicitly) that makes you one of them. Of course, we’re really just trading one obvious sexual metaphor for another when Michael gets tricked into drinking from a blood-filled wine bottle, because while there may be no penetration, David still has Michael ingesting his bodily fluids. 100,000 truck stop men’s room glory holes wink in recognition.

Anyway, it doesn’t take Sam or Lucy long to notice that Michael has started behaving strangely— sleeping late, staying out all night doing God knows what, wearing his sunglasses indoors as if even the dimmest sunlight were torture for his eyes, etc. Although Michael remains carefully “in the closet” with his mom, fobbing off her every attempt to reach him with vague statements about “going through stuff” that he’d rather not talk about, he has to come out to his brother in order to explain an altercation between him and Sam’s husky, Nanook. Whether we call the point of contention vampirism or homosexuality, Sam’s reaction to the news— shock, concern, fear, love, supportiveness, and a formless sense of betrayal, all tied up in an enormous knot of confused and conflicting emotions— is the most well observed and honestly written thing in this entire film. Now that he knows what’s behind his brother’s formerly baffling lifestyle and personality changes, Sam suddenly realizes what the Frog brothers have been trying to tell him all this time with their stupid vampire comics. They’ve known all along that Santa Carla’s outrageous murder rate is the result of a vampire infestation! And hot upon the heels of that understanding comes a bit of new hope: maybe Edgar and Alan will know of a way to cure Michael. When asked, the brothers explain that so long as a vampire has not yet made its first kill, it can be restored to humanity if the master of the clan that turned it is destroyed. That’s the good news. The bad news is that Sam doesn’t know about David and his gang, so he has no idea who the local master vampire might be. And even if he did know about Michael’s undead biker buddies, should we really be so quick to assume that just because David is the leader of the Lost Boys, he must also be the master vampire of Santa Carla?

The Lost Boys is another one that feels like two different movies intertwined and spliced together, and with good reason. The original script by Janice Fischer and James Jeremias was for a film about vampire children, really pushing the Peter Pan angle and aiming for something like a horror version of The Goonies. Director Joel Schumacher didn’t want to make that movie, though, and since the producers really wanted him for some reason, he got their okay to cast Michael, Star, and the vampire gang as teenagers instead. That inevitably brought sex into the equation, and with it the gay subtext so blatant that it practically qualifies as text. Quite a bit of the old, Goonies-inspired material remains, however, in the form of the Frog brothers and their intervention. Whenever Edgar and Alan show up, The Lost Boys turns zany in a way that sits uneasily beside the slick, achingly self-conscious cool of Michael’s side of the film. Still, Corey Haim and Corey Feldman play off each other well enough to redeem all but the worst of the kiddie comedy, so that it’s no wonder the two boys spent the remainder of the decade appearing together in one movie after another.

I said before that the main thing the vampire movies of the late 80’s took from Fright Night was an MTV-influenced esthetic sense, and The Lost Boys is probably the ultimate example of the phenomenon. Most immediately obvious are the artificial fog, the neon lights, and the costumes indiscriminately mixing the tribal signifiers of youth subcultures that were usually at each other’s throats in the real world, but it goes deeper than that. In the manner of Flashdance, The Lost Boys features entire sequences that could be popped out whole to serve as music videos for whichever pop or faux hard rock song happens to be on the soundtrack at the time. The family’s arrival in Santa Carla establishes the pattern by setting a montage of off-putting local color to Echo and the Bunnymen’s cover version of “People Are Strange.” The bike race/chicken match whereby Michael is initiated into David’s gang is accompanied by most of Lou Gramm’s “Lost in the Shadows.” The scene in which Star helps Michael give heterosexuality one last try could have functioned as the video for Gerard McMahon’s “Cry Little Sister,” although the imagery might have been just a tad too steamy for airplay in the days of Tipper Gore. My God, when one of David’s vampires gets impaled onto the comically immense stereo in Grandpa’s den, the machine inexplicably manages to blare a quick chorus of the Jimmy Barnes-INXS version of “Good Times” while shorting out and electrocuting the bloodsucker’s carcass until it explodes!

Now I’m sure all that sounds unconscionably cheesy, and frankly a lot of it is. But Schumacher frequently makes it work anyway, which is not something I’m accustomed to hearing myself say about him. Partly, the setting and the subject matter just lend themselves to his hacky, shallow, glamour-fixated style. We’re dealing, after all, with a pack of teens who want to be vampires so that they can remain young, sexy, carefree, and irresponsible forever, and they live in a town that basically exists as a life-support system for a carnival on the beach. But Schumacher also had a secret weapon without which I think he would still have been completely screwed. More than anything else, it’s Kiefer Sutherland’s performance that makes The Lost Boys tick. I’m not going to lie— in 1987, when I was thirteen years old, I thought David was the coolest guy I’d ever seen. Sutherland is basically just doing Ace Merrill from Stand by Me over again, but if you’re good at something, you might as well keep at it. In his youth, Kiefer had an effortless, swaggering charisma that couldn’t be further from his father’s default setting of Bookish Weirdo. He’s perfect for a character who’s supposed to be dangerous because he’s seductive, and seductive because he’s dangerous. And he’s equally perfect for a film that has to hide the real source of its sex appeal behind a straight relationship that isn’t fooling anybody. He’s the ultimate closet-case lust-interest, because you can’t tell whether you want to fuck him or to be him.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact