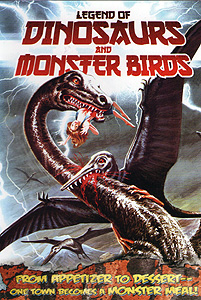

Legend of Dinosaurs and Monster Birds / Legend of the Dinosaurs / Kyoryu Kaicho no Densetsu (1977) -**

Legend of Dinosaurs and Monster Birds / Legend of the Dinosaurs / Kyoryu Kaicho no Densetsu (1977) -**

Late in 1976 and early in 1977, when everybody the world over was assuming that the Dino De Laurentiis King Kong would be the biggest thing since the Empire State Building, a lot of cash-in projects got green-lit. Most of them were giant ape movies of one sort or another, but some producers had more expansive visions. The strangest Dino-Kong coattail-rider that I know of sadly never got made. It was called Nessie, and it was to have been a joint venture by Hammer Film Productions and the Japanese Toho studio. Details have been hard to track down, but evidently the premise was that the Loch Ness Monster would leave its home waters for some ecological reason, and go on a kaiju rampage across the British Isles. Alas, this was the period when Hammer could barely secure financing for a trip to the pub, so Nessie inevitably fell apart before a single frame was shot.

That may not be quite the end of the story, though, because right around the time Nessie was supposed to come out, Toho’s competitors at Toei released Legend of Dinosaurs and Monster Birds. The setup for Toei’s film is suggestively similar to that of the aborted Nessie: climate anomalies and seismic activity revive prehistoric reptiles to terrorize the communities around a legendarily monster-haunted lake. Furthermore, one of those creatures is a Plesiosaurus. That’s significant because during the 1970’s, the most popular theory to explain the Loch Ness Monster was that it was a plesiosaur that had somehow escaped extinction in the Mesozoic Era. It therefore seems reasonable to presume that Nessie would have rendered the monster as a plesiosaur, too. Beyond that, the Plesiosaurus here is directly equated with the Loch Ness Monster by two different characters. What it looks like, then, is that Toei rushed a Nessie rip-off into production, and then persisted with the project even after its inspiration was shitcanned, perhaps out of faith that King Kong would revive interest in giant monsters, which was then flagging even in Japan. So those of us who are inclined to long for Nessie can think of Legend of Dinosaurs and Monster Birds as a consolation prize— and while we may grumble over what a crummy one it is, any sober assessment indicates that Toho and Hammer teaming up to copy Dino De Laurentiis would have yielded crummy enough results itself.

Don’t ask me why Yanomo Takami is wandering around in the woods below Mount Fuji; frankly, I don’t think the filmmakers know what she’s doing up there, either. (You also shouldn’t bother asking me who plays her— this movie’s credits are even more unhelpful than Dolemite’s.) All that matters, anyway, is that she plants her foot in just the wrong place, and plunges through a gap in the roof of a hitherto undiscovered cave. When Yanomo recovers from the fall, she finds herself in a strange, cold chamber filled with obelisks of ice, and against one wall, what appear to be fossilized eggs bigger than she is. Then, impossibly, one of those stone eggs begins to hatch. Yanomo doesn’t stick around long enough to get a good look at whatever’s inside. The huge, luminous eye she sees peeking through the widest crack in the shell is enough to send her fleeing at top speed until she fortuitously finds her way back to the surface, where she is picked up and taken to safety by a construction crew.

Her curious story makes the national news, which bundles it together with reports of other unusual natural phenomena— earthquakes, a freak midsummer cold snap in Hokkaido, that sort of thing. The business about the petrified egg catches the attention of a geologist named Ashizawa (Tsunehiko Watase, from Delinquent Girl Boss: Worthless to Confess and Virus), because it reminds him of something his father claimed to have seen in much the same area. Ashizawa the elder went so far as to contend that the egg he found indicated the survival of dinosaurs into the present day, which understandably led to his professional disgrace. His son believed him, though, and with what looks like an opportunity to restore the old man’s reputation (and, or so he surmises, to get rich in the process) dangling before his face, Ashizawa blows off a conference he was supposed to attend in Mexico to pay a visit to Mount Fuji instead. He gets caught in an earthquake before he can find the Takami girl’s cave, however, and is knocked senseless by a chunk of falling debris.

Luckily for Ashizawa, he wasn’t the only man prowling those woods at the time. When he comes to, Ashizawa finds himself in the very cabin his father used to own, which is now being used by Chohei (billing order suggests that this might be Shotaro Hayashi, of Message from Space and Girl Boss Guerilla), an old prospector friend of his. Chohei, of course, was the one who rescued Ashizawa from the quake, and the pair soon get to talking about Miss Takami’s petrified eggs. Chohei knows the cave in question, and he also knows that it communicates underground with Lake Sai, one of five lakes overshadowed by the volcano. That’s significant for Ashizawa’s purposes, because in local lore Lake Sai is the lake of the dragon. One of Papa Ashizawa’s living dinosaurs, maybe?

This is an opportune time to visit Lake Sai if dragons (or dinosaurs) are your thing, because it happens to be the week of the Dragon Festival. And as you’ll quickly recognize if you pay any attention at all, that means Legend of Dinosaurs and Monster Birds has abandoned whatever King Kong cash-in plans Toei might have had in favor of ripping off Jaws instead. A pair of tourists scuba diving in the lake disappear. So do two more riding a rented paddle boat. Junko (Tomoko Kiyoshima), one of two journalists covering the festival for the local paper, has a terrifying experience when she comes upon a dismembered horse in the forest. In the course of sticking his nose into all that stuff, Ashizawa befriends Junko’s partner, Akiko (Nohiko Sawa), giving him a front-row seat to the escalating weirdness. Eventually, on the climactic day of the festival, a couple of teenaged jackasses whom we’ve been seeing off and on since Ashizawa arrived are killed after playing a stupid prank (one lifted directly from Jaws, I might add) by a huge Plesiosaurus. And by “huge,” I mean the head of this thing alone is only slightly smaller than the torso of the real deal. The prehistoric monster goes all Bruce the Shark on the communities around Lake Sai, ending the Dragon Festival on a note of panic, and forcing the authorities to dust off one of the oldest ploys in the critter-flick playbook. That’s right, it’s a pocket-sized version of the venerable depth charge attack— which, in traditional style, comes a lot closer to killing Ashizawa and Akiko (who happen to be looking for the creature’s lair at the time) than it does to giving the lake monster so much as a tension headache. And just when it looks like things can’t get any worse, that egg that everybody seems to have forgotten about finally finishes hatching, unleashing a Rhamphorhynchus even more indefensibly oversized than the Plesiosaurus! The people of Lake Sai are just lucky that the two creatures are apparently natural enemies, and that the awakening of Mesozoic reptiles is apparently Mother Nature’s cue to provide a volcanic eruption to finish off whichever of them wins the fight.

It amuses me that a movie called Legend of Dinosaurs and Monster Birds has, technically speaking, neither any dinosaurs nor any monster birds in it. Still, I have to applaud the choice of monster species here— especially the Rhamphorhynchus, which was my favorite pterosaur prior to the popularization of Quetzalcoatlus. Remarkably, both puppets are fairly recognizable as what they’re supposed to be, too. The pterosaur even has those amazing outward-jutting teeth. To say that they’re recognizable is not the same thing as to say that they’re good, however. Indeed, these are some of the sorriest prehistoric reptiles you’ll see in any movie that doesn’t just glue a Dimetrodon sail onto the back of a baby alligator. But in true kaiju eiga style, the movie gives both puppets in all their cheesy glory the star treatment without a trace of embarrassment. That starts to feel weird in the second half, when Legend of Dinosaurs and Monster Birds gets really serious about ripping off Jaws. After all, keeping the shark offscreen as much as possible was one of the keys to the latter film’s success, and nearly all of its other imitators followed suit more or less.

If you’re finding it hard to imagine how a kaiju flick that is also a Jaws knockoff would work in practical terms, it won’t surprise you to learn that at least in this case, it basically doesn’t. Director Junji Kurata seems to have failed fundamentally to get the premise of a huge monster operating by stealth and picking off its victims one and two a time in secret. That is what the plesiosaur does, you understand, but I’m left with the impression that Kurata didn’t see the point of so furtive a monster rampage. He similarly looks to have approached the Dragon Festival plot thread as pure cargo-cult filmmaking, evincing no awareness of why the film’s three screenwriters included it beyond that the Fourth of July weekend was for some reason a big deal in the movie they were copying. Significantly, the idea of cancelling the festival never comes up, and the plesiosaur in any case limits its direct interference with the celebration to head-butting the floating stage where country-and-western singer Akira Moroguchi (yes, there apparently is such a thing as Japanese country-and-western music) is performing. So instead of creating an escalating sense of tension, raising the stakes for the Lake Sai communities, or creating an economic disincentive for the folks in charge to admit that there’s a monster in the lake, the plesiosaur’s sneakery is merely boring, and the Dragon Festival is merely a pointless distraction. The Rhamphorhynchus, oddly enough, feels just as rote, but from the opposite direction. One monster hadn’t been enough for a proper kaiju eiga since the mid-1960’s; obviously, then, the Plesiosaurus needed a sparring partner, even though resolving the story that way would accomplish nothing but to deprive the human protagonists of any meaningful agency. Not for nothing does Legend of Dinosaurs and Monster Birds just stumble to an exhausted halt after one creature kills the other, only to be swallowed up by the earth. The filmmakers have long since lost any interest in the human characters beyond the question of their bare physical survival, and by that point so have we. Nearly the only form of interest that Legend of Dinosaurs and Monster Birds is capable of sustaining from beginning to end is a vague, morbid fascination with its almost limitless ingenuity in the field of audience disappointment.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact