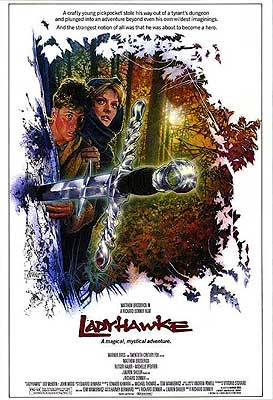

Ladyhawke (1985) **½

Ladyhawke (1985) **½

Rutger Hauer starred in two relatively lavish Medieval movies in 1985, and they make interesting side-by-side viewing. As we’ve already discussed, he headed up the cast of Paul Verhoeven’s first English-language film, Flesh & Blood. But shortly before that, Hauuer got second billing in Richard Donner’s Ladyhawke. Apart from the presence of a scandalous clergyman in each, and the odd fact that both of Hauer’s characters wield gigantic claymores as their weapon of choice, the two pictures could hardly be more different. As you would expect from Verhoeven, Flesh & Blood is grimy, squalid, violent, and lascivious, delighting in battles, executions, political and religious corruption, disease, and rape. Especially rape. Also, unusually for a movie set in the Middle Ages and released in the wake of Excalibur, Flesh & Blood’s fantasy content is muted in the extreme, limited to a quasi-magical interpretation of Renaissance science. Ladyhawke is a much gentler film. Watching it, you don’t feel as though you can smell the sheep shit and unwashed armpits through the screen. Its violence, while frequently lethal, is mild enough in presentation that I’d say the MPAA ratings board was unduly harsh in giving it a PG-13 certificate. And most of all, its central male-female relationship is a matter of chaste and courtly love instead of a complicated tournament of strategic fucking. Ladyhawke is overtly a fantasy movie, too, with the couple at its core laboring to get themselves out from under an ingenious curse of incompatible lycanthropies.

Beneath the fortified episcopal see of Aquila, which may or may not be the real town of that name in Switzerland (but almost certainly is not the one in the middle of Italy), there is a dungeon notorious throughout the land for its imperviousness to escape. And in one of that dungeon’s grubbier cells, there sits imprisoned a long-wanted thief called the Mouse— or, to give him the name by which his mother no doubt calls him, Philippe Gaston (Matthew Broderick, from Godzilla and The Stepford Wives). Gaston is due to be executed today, and he doesn’t much fancy the idea. Luckily, the drainage flue in the floor of the cell leading down into the municipal sewer is just barely wide enough for a pencil-neck like him to squeeze through it, so when Captain Marquet (Ken Hutchinson, of I Am a Groupie and Deadly Strangers) comes to collect him, he finds nothing but the Mouse’s cellmate having a good laugh at the authorities’ expense.

The Bishop of Aquila (John Wood, of WarGames) is not pleased to hear of Gaston’s vanishing act. The Mouse is of little consequence in and of himself, but the bishop does care a great deal about the fearsome reputation of his dungeon. If an infamously inescapable prison is to remain infamous, it must also remain inescapable. Gaston therefore has to be rounded up immediately, before he has a chance to start telling tall stories about his breakout. Fortunately for His Holiness, Gaston is an extremely foolish young man. He pauses in his flight at the very first inn down the road from the castle, arriving while Marquet and his men (who had gone there to listen for rumors of the Mouse’s passing) are waiting for their first round of drinks to be served. Less to the bishop’s advantage, one of the inn’s other customers is well acquainted with Marquet, and doesn’t like him very much. In fact, that other customer— Etienne Navarre (Hauer) is his name— used to do Marquet’s job before he was sacked on grounds that he evidently still considers unjust. No sooner do the captain’s soldiers have Gaston in custody than Navarre intervenes, trouncing the whole squad singlehanded. Then Navarrre grabs Gaston, and rides off with him to the relative safety of a farm on the edge of the forest, tenanted by two visibly loony peasants.

A bunch of odd stuff happens that night. There’s a wolf loose in the woods, for one thing— a big, black bastard with no pack in evidence, but who seems plenty dangerous enough all by himself. When Gaston runs to Navarre’s stall in the stable where the farmers put them up, hoping that Etienne will kill the beast, there’s no sign of the knight there or anyplace else. Etienne’s falcon seems to be gone, too, but Philippe shows no sign of noticing that. What Gaston does find is a third guest at the farm whom he hadn’t seen during the day, a beautiful young blonde woman (Michelle Pfeiffer, from Wolf and What Lies Beneath) who stuns him by walking right up to the wolf and taming him as if he were her personal house pet. She spends the whole night out in the forest with the animal while Philippe hides in the stable, too freaked out to sleep until just before dawn.

The girl and the wolf are both gone the next morning, while Navarre and the falcon have returned. That pattern repeats itself with each rising and setting of the sun for the next few days, until even the dimmest of us will have figured out that Navarre is the wolf and the blonde is the falcon. Gaston, however, is apparently dimmer still, and requires a glaringly obvious demonstration of what’s going on. He gets it after he and Navarre clash a second time with Marquet’s forces, and one of the bishop’s guards shoots the bird (which was providing surprisingly effective air support in the fighting) through the wing with a crossbow. Panicking far more than seems reasonable over the fate of a falcon (well, duh…), Navarre charges Gaston with the mission of taking the bird to a ruined church where the disgraced monk Imperius (Leo McKern, of X: The Unknown and The Day the Earth Caught Fire) lives as a hermit. Etienne gives no more explanation than to say that the old man will know what to do, and indeed he does. The instant Gaston mentions that the injured falcon belongs to Navarre, Father Imperius hustles him inside, relieves him of the animal, and retreats with it into a sort of laboratory in the depths of the building. The monk doesn’t want Philippe to see what he’s up to for some reason (again, duh), but good luck keeping secrets from a professional thief. When the Mouse’s snooping that night reveals that the falcon, as usual, is gone, and that the blonde girl, as usual, is back— bearing a crossbow wound exactly equivalent to the bird’s, no less— Gaston catches up at long last with the audience.

Meanwhile, back in Aquila, the bishop is most disturbed to learn that Etienne Navarre is on the prowl, and that he, of all people, is protecting the escapee from the dungeon. Also, oddly enough, the bishop is severely worked up over the ex-captain’s falcon, and gives Marquet explicit orders that no one is to harm it under any circumstances. Obviously he’s aware of the bird’s dual nature— as well he should be. Imperius knows the full story, so let’s pay attention when he explains it to Gaston. Some years ago, His Holiness fell in love with a noblewoman named Isabeau. Officially speaking, that put him in “sucks to be you” territory, but let’s be realistic here. This is the late Middle Ages we’re talking about. If Pope Alexander VI and his drinking buddies can gamble fortunes on naked hooker races in the Vatican banquet hall, then surely the Bishop of Aquila can have an affair with a daughter of the lesser nobility. The real obstacle, rather, was that Isabeau was already spoken for. What’s more, the man she loved was none other than the bishop’s own captain of the guard! So as one comes to expect of fictional evil clergymen, the bishop played the “if I can’t have you, no one can” card, and resorted to black magic. Calling upon the power of Satan, he cursed Isabeau and her lover to take on animal form for half their lives— her by day, and Navarre by night. They could spend every minute within arm’s reach of each other until the day they died if they felt like it, but they would never be together. Navarre understandably devoted the next several years to a quest for some counter-spell, but came up empty-handed. Now his quest is to kill the author of his and Isabeau’s suffering, seeking revenge where restitution failed.

It turns out, however, that Etienne’s search was not as thorough as he believed. There is a way to break the curse, and better yet, Imperius has discovered it. It’s really very simple. All Navarre and Isabeau have to do is to stand before the bishop together as man and woman, to confront him with the situation that his sorcery was meant to prevent. Once they do that, they’ll never have to worry about unwanted shape-shifting ever again. Of course, they can’t very well perform the prescribed counter-spell if the bishop is dead, so Navarre’s revenge will have to wait if he knows what’s good for him. The knight is not impressed, though, when Imperius explains it to him, and I expect you can see why not. The whole point of the curse is that Isabeau is a hawk so long as the sun is shining while Navarre is a wolf so long as it isn’t, meaning that the conditions of the monk’s cure are impossible to satisfy. Still, Imperius swears there’s a way— something about “a day without a night and a night without a day” which are supposed to occur later this very week. Navarre scoffs and rides off to Aquila anyway, but this is a situation in which it would pay to listen to those more educated than oneself. There are these things called eclipses, you know, and even Western astrologers were starting to get pretty good at predicting them by the 15th century.

I wanted a little more from Ladyhawke, although I confess that I’m not exactly sure what I wanted more of. Maybe the problem is simply that the focus of the film is misplaced. This story rightfully belongs to Etienne and Isabeau, but we see it instead from the Mouse’s point of view. Granted, it wasn’t long ago that I praised Strange Days for adopting a similarly skewed perspective, but there’s an important difference. In that movie, Lenny Nero had a story of his own that kept intersecting with that of the more momentous events unfolding in premillennial Los Angeles. Philippe Gaston, however, has nothing going on independent of the clash between the cursed lovers and the evil bishop from the instant Navarre comes to his rescue at the tavern. He’s strictly a sidekick, and not even a very interesting one. Also, he’s played by Matthew Broderick, which raises problems of its own. I like Broderick in Ernest Young Nebish mode, but his Smarmy Trickster routine is hit-or-miss for me. This rendition of it is very much a miss.

Ladyhawke also disappoints on the action front. I’ve already mentioned that the sword-fights are remarkably bloodless even for a PG-13 film, but the trouble is that that sentence works just as well for figurative readings of “bloodless” as it does for the literal one. Hauer and his various opponents rarely seem to have their hearts in a battle, with the result that Ladyhawke’s most satisfying action sequence is the one that has Father Imperius leading the bishop’s soldiers on a merry chase through his dilapidated church, pressing this and that bit of crumbling masonry or rotted timber into service as makeshift booby traps along the way. The climactic duel between Navarre and Marquet is especially listless, and suffers from an ill-considered inversion of the race-against-time trope. Because a happy ending depends upon Navarre not killing the bishop until after the eclipse is in full swing, suspense in this scene works backwards, and director Richard Donner never quite comes to terms with the unusual demands thus placed on the sequence.

Then there’s the music. Frankly, I have no idea what Alan Parsons (yes, that Alan Parsons) was thinking. The mood of nearly every cue is at least slightly wrong for the action it accompanies, almost as if Parsons had cobbled the score together from library music instead of composing it himself. That stock-music sensation is further heightened by how totally devoid of personality much of Parsons’s work is. So far as our ears are concerned, Ladyhawke could be virtually any sword-swinging adventure movie of the preceding 30 years. Or at any rate, it could be that half the time. The other half, Parsons asserts his musical identity at full force with risibly inappropriate prog-rock themes. Modernist scores can work for fantasy movies set in some mythologized version of the distant past. Tangerine Dream’s synth-heavy Legend soundtrack, for example, is one of the most successful elements of that frustratingly uneven film. But when Parsons really cuts loose on Ladyhawke, the result is less Legend than Hearts and Armour or Hawk the Slayer.

All that notwithstanding, Ladyhawke does shine a bit when it concentrates on the central through-line of the two lovers doomed to be eternally separated despite their inseparability. The mechanics of the bishop’s curse feel exactly like something a Medieval troubadour would have dreamed up, counteracting such disruptive modernizing elements as the soundtrack’s wailing guitar solos and Matthew Broderick’s stubbornly 20th-century characterization of the Mouse. The scene around the end of the second act when we (and Gaston) are at last privileged to see Isabeau and Etienne transforming past each other is the principal highlight of the film, pulling many times the emotional weight of the too-pat resolution. Hauer is believable as usual as a man all out of patience with his lot, and too bent on getting back at his enemy to listen to good news when he hears it. And remarkably, given the kind of parts I associate with Hauer in the 1980’s, he puts across Navarre’s implacability without becoming straight-up terrifying. Michelle Pfeiffer doesn’t have much to do, but she’s perfectly adequate for what the movie asks of her. Finally, let’s not overlook the importance of John Wood’s bishop. It isn’t a flashy performance, nor will it earn Wood a featured spot in the annals of cinematic villainy. For the purposes of this story, though, it’s vital that the bishop seem no more sinister than any other prince of the Medieval church. His dabbling in Satanic sorcery is supposed to be a secret, after all, something that no one save Father Imperius and the two actual victims of the bishop’s curse would even suspect. It is to Ladyhawke’s advantage, then, that Wood is so close here to his more famous turn as the prickly but kindly Professor Falken. Unless you’d been cursed by him or locked in his dungeon, you might mistake the bishop for prickly-but-kindly, too.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact