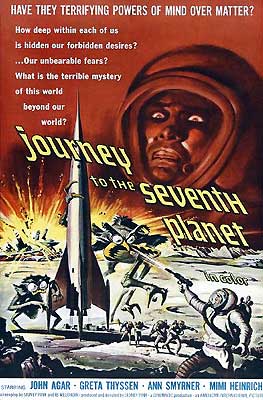

Journey to the Seventh Planet (1962) **˝

Journey to the Seventh Planet (1962) **˝

So it turns out that Reptilicus was not the only product of Sid Pink’s early-60’s sojourn in Denmark. Shortly after stunning the world with regenerative, acid-puking dragons and (even more terrifying!) “Tivoli Nights,” Pink teamed up again with frequent collaborator Ib Melchior on a virtual remake of their delightful The Angry Red Planet. This time, though, they’d send their intrepid astronauts a further three orbital pathways out, to a world largely neglected by mid-century sci-fi movies. That said, the challenges awaiting the international rocket crew of Journey to the Seventh Planet on Uranus would bear a marked resemblance to what their all-American predecessors encountered on Mars. They’d recall the experiences of a different fictional Mars mission, too, for Pink and Melchior’s Uranus owes a lot to the Red Planet as imagined in Ray Bradbury’s short story, “Mars Is Heaven” (or “The Third Expedition,” for those of you who know it from its second incarnation as a chapter in The Martian Chronicles).

In the year 2001, the United Nations launches the first-ever manned mission to Uranus, in response to the discovery of unusual radio signals emanating from that distant world. The assumption is that the waves are the product of some unknown natural, physical phenomenon, some property of the planet itself not predicted by current scientific thinking about the environment there. Nevertheless, the crew of the Explorer 12— Eric (Carl Ottosen, of Reptilicus and I, a Woman, Part II), Don (John Agar, from The Daughter of Dr. Jekyll and Zontar, the Thing from Venus), Barry (The Reluctant Sadist’s Ove Sprogře), Svend (Louis Meihe-Renard), and Karl (Peter Monch)— are well trained and equipped for an encounter with extraterrestrial life. That’s good, because Uranus is indeed inhabited, and the intelligence dwelling there means harm not only to the Explorer 12 astronauts, but to their homeworld as well.

The thing on Uranus is a sort of giant, telepathic brain, capable of almost godlike manipulation of its planet’s environment. I gather, however, that a hermit’s existence is boring even for the nigh-omnipotent, because the brain has decided to take its show on the road. To that end, it means to capture Eric and his men, and to seed their nervous systems with fragments of its own consciousness. When the Explorer 12 returns home, the rocket’s crew will thereby act as the alien’s invasion force. However, there is evidently at least one limit to the creature’s power, in that the consciousness-seeding operation can be performed only at close quarters. The space brain can probe the astronauts’ minds at orbital range, learning everything it needs for a campaign of trickery against them, but an attack in the strict sense will have to wait until the humans are safely on the ground.

That attack, when it comes, is well chosen for use against explorers— the brain gives Eric and his men a mystery to solve. Several mysteries, actually. Upon making landfall on Uranus, the Explorer 12 crew find not the hostile alien environment they expected, but an eerily exact simulation of Earth, pieced together from things they each associate with comfort, pleasure, and safety. A forest Svend knows like the back of his hand (except insofar as this version is heavily stocked with the apple trees that are synonymous with home in Barry’s imagination) surrounds the little Danish village where Eric grew up. And as if that weren’t weird enough, the sparse population of the village seems to consist entirely of girls who loom large in the astronauts’ fantasies, from old flames to unrequited crushes to the pinup babes of which Don is such a connoisseur. The latter appear friendly enough— especially Eric’s first love, Ingrid (Ann Smyrner, from Mission Stardust and House of 1000 Dolls), and Don’s current men’s-magazine lust-object, Greta Thyssen (whom we’ve seen before in Terror Is a Man)— but also suspiciously fixated upon splitting the astronauts up and getting them alone somewhere. Eric and the others (even the ebulliently randy Don) are commendably too careful to be taken in by that ploy, but there’s also the enigma of the dome to lead them on. The area of pseudo-Earth is bounded by a dome of force unlike anything known to human science, outside of which Uranus presumably shows its true colors. Since that’s what the men are really here to investigate, and since there’s no sign within the dome of the mysterious power creating it, the astronauts swiftly begin laying plans for a foray into the unknown territory beyond. Again, though, they’re too careful for the brain’s liking, making an armed reconnaissance in force rather than sending out a single, vulnerable scout. Alright, then— no more Mr. Nice Brain. If the Explorer 12 crew can’t be lulled into a false sense of security by pleasant surroundings, if they can’t be tempted into the creature’s clutches by appeals to their sex drives or senses of adventure, then perhaps they can instead be chased to their doom by the things they most fear.

As compared to The Angry Red Planet, Journey to the Seventh Planet is smarter, more ambitious, chintzier, and less successful. The monster encounters in the earlier film were just sort of things that happened, more or less at random and with no pattern or theme deeper than that each successive creature was bigger and more formidable than the last. The eventual revelation that all life on Mars belonged to a single, highly intelligent hive-mind was not inconsistent with what we had previously been shown, but neither did it cast any of the foregoing action in a clarifying new light as it might have. Here, though, there’s a clear unifying purpose to all the weird things going on; it’s all about psyching out the Explorer 12 crew so that the space brain can get its axons on them. And what’s more, the methods the space brain uses are just what we might expect from a being that knows everything there is to know about Eric and the others, but lacks the life experience necessary to attach the correct meanings to all that data. The brain wants to put the astronauts at ease and off their guard, so it creates a composite version of their homes. It wants to entice them toward itself and away from each other, so it manufactures fantasy sex objects to seduce them. But it fails to grasp as it does so that its intended prey come from a place where material reality is fixed, and that the manifestations it concocts, pleasant though they may be, will therefore make the interlopers much warier than they would have been had they merely found a seemingly lifeless world of perpetual storms and ammonia snow. Journey to the Seventh Planet ends up being a remarkably astute exploration of a possible non-human psychology.

That emphasis on unreality and the world of the mind gives Journey to the Seventh Planet something of the feel of a European sci-fi comic, a feel which is emphasized and intensified by the look of the film. The Bava-esque lighting and vibrantly colored costumes (especially the astronauts’ space suits, inexplicably patterned in the royal blue and police-line yellow of the Swedish flag) suggest the crude four-color printing that was then the state of the art in the comics industry, while the combination of whimsical design and hyper-realistic detail in the futuristic equipment anticipates the style of such Euro-comics luminaries as Moebius and Philippe Druillet. What survives of the original Danish special effects (more on that in a minute) is comic-booky, too, with its emphasis on superimposed swirls of colored light and the like. Mind you, there is a downside to resembling Euro-comics, at least the way this movie does it. Journey to the Seventh Planet’s most serious weakness is a narrative sponginess that I’ve encountered a lot in that medium— stories full of small holes, that won’t bear much weight or maintain form well under pressure. Characterization here is vague and inconsistent, motivations are poorly thought out, and the final act is limp and ill-focused. Still, this is a commendably unusual film to see released under the imprimatur of American International Pictures.

Now about those special effects… Those of you who have seen Reptilicus will not be surprised to learn that Journey to the Seventh Planet was, materially speaking, a shoddy production indeed. When the space brain finally decides to trade in the carrot for the stick, the result is a succession of encounters with monsters drawn from the astronauts’ most primal and irrational phobias, and it was the opinion of studio heads Samuel Arkoff and James Nicholson that those sequences were so goofy-looking as to render the movie unreleasable. The producers took a couple different approaches to the problem. Most successfully, they hired Jim Danforth, then just beginning to emerge as a stop-motion maestro, to replace the rat monster drawn from Karl’s nightmares, which Danish effects boss Bent Barfod had rendered as a crude full-scale marionette. The resulting creature resembles a cross between a one-eyed squirrel and an Allosaurus, and absurd as that sounds, it’s surprisingly effective. For the later giant spider attack, the original, laughably lame puppet (which can be briefly glimpsed in the shot of the monster being crushed by falling rocks) was excised in favor of stock footage from Earth vs. the Spider, tinted blue in the hope of at least sort of matching the surrounding full-color material. The lighting in the cavern set is awfully blue, to be sure, but the trick still doesn’t quite come off. Finally, for the death of one astronaut absorbed into the brain itself, the producers resorted to a conceptually similar clip from The Angry Red Planet. That created a problem 20-odd years down the line, when Orion Home Video issued that movie and this one together as a double-feature laser disc. The recycled bit was snipped from Journey to the Seventh Planet, leaving it difficult to sort out what exactly is supposed to be happening to the crewman who bites it at the climax. Vexingly, that artifact of circa-1990 marketing decisions persists today, even though the original rationale for it no longer pertains. MGM’s “Midnight Movies” DVD edition pairs Journey to the Seventh Planet not with The Angry Red Planet, but with Invisible Invaders, yet it reuses the compromised Orion laser disc edit anyway. Meanwhile, it appears that anyone wishing to see Journey to the Seventh Planet in its intended form is straight out of luck. The film was never released in Denmark at all, and no prints featuring the original effects footage have yet turned up, either there or in American archives.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact