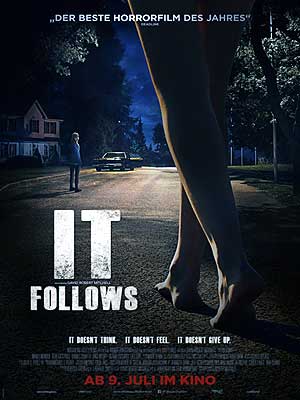

It Follows (2014/2015) ***½

It Follows (2014/2015) ***½

Horror seems to attract more half-baked Freudianism than any other genre. Just for starters, witness Carol Clover’s Men, Women, and Chainsaws (which we’ve had occasion to discuss before around here) and James B. Twitchell’s Dreadful Pleasures: An Anatomy of Modern Horror (which hilariously attempts to root all horror fiction, film, and graphic art in the incest taboo). To be fair, the genre does bring a lot of it on itself, since sex is so obviously lurking in the background of so many of its characteristic tropes, and is frequently lying right out on the surface with its hands down its pants. Nevertheless, Freudian interpretations of horror are frequently such obvious, overreaching bullshit that it remains startling to encounter a fright film in which the sexual metaphor is not just plainly deliberate, but plainly deliberate as a metaphor. It Follows is one of the rare horror movies that deal consciously and specifically with sexual anxieties (as opposed to those that merely get their terror tangled up with their titillation), and is more unusual still for locating those anxieties not in the messy machinery of the human body, but in the social, psychological, and hygienic risks attending the question of whom to fuck, when, why, and how. It’s also the most technically adroit new scare picture I’ve seen since probably The Ring, virtually its every moment constructed so as to place the viewer in the same emotional position as its harried protagonist.

Nighttime— a quiet neighborhood in the suburbs of Detroit. A twentyish girl named Annie (Bailey Spry, from Age of Ice) sneaks out of her house, clad only in pajamas much too sexy to pass muster in public. She frantically scans all the approaches to her position— all the streets, all the yards, all the visible passages between houses— and then runs back inside as her father (Loren Bass) begins concernedly calling out to her from upstairs. In a flash, she’s back out on the street, this time carrying her car keys, and there’s a note of near-panic in her dad’s voice. Annie’s not waiting for anything, though. She jumps right into her car, speeds off, and doesn’t stop driving until she reaches what I take to be the shore of Lake Erie. Shortly before dawn, as Annie sits huddled beside the campfire she built on the beach, she notices someone walking slowly but implacably toward her. When her corpse is discovered some hours later, it’s in such a condition that they’ll still be talking about it years from now at the medical examiner’s office.

Meanwhile, Jamie Height (Maika Monroe, from Flying Monkeys and Bad Blood), another suburban Detroit girl, might have a new boyfriend. She doesn’t know Hugh (Jake Weary, of Zombeavers) well enough yet to satisfy her sister, Kelly (Lili Sepe), or her best friends, Paul (Keir Gilchrist, from Dead Silence and Dark Summer) and Yara (Olivia Loccardi), when they grill her on the subject, but there have definitely been some sparks. She’s got her first real date with the guy coming up this weekend, so maybe she’ll be able to give a better accounting of him come Sunday.

Jamie and Hugh’s first date is weird; their second is disastrous. On the initial outing, they enjoy a nice dinner together and seem to be having fun during the wait for their movie to start, but then Hugh is suddenly overcome by what he says is a bout of wooziness. That’s not what it looks like, though. What it looks like is that the boy saw someone in the theater whom he really didn’t want to, and bullshitted up a pretext for leaving before they could make contact. The next time the new couple go out together, they end the night parking in the overgrown lot beside an abandoned high-rise garage. One thing leads to another, and soon they’re taking full advantage of the giant back seat in Hugh’s mid-70’s Chrysler New Yorker. That’s when the evening earns its place in the annals of legendary bad dates. Hugh chloroforms Jamie, and when she comes out from under the drug, she’s tied to a wheelchair, still in her underwear, on the topmost interior level of the garage. Hugh doesn’t do her any physical harm, but he freaks her out good and proper with the craziest fucking story she’s ever heard. He tells her that something is going to begin following her. Who knows what it really is, but it will always take the form of a person— maybe a stranger, maybe someone familiar, maybe even somebody she loves. It always goes on foot, slow as cold molasses, but it absolutely will not stop until it catches her. And despite the seeming mindlessness of its pursuit, the thing isn’t stupid. There’s only one way to get rid of it: Jamie needs to have sex with somebody. Then it will leave her alone and go after that person instead. Unfortunately, there’s also a catch. If the thing succeeds in killing the person onto whom she passes it along, it will turn around and resume its pursuit of her. That’s one reason why Hugh is going to such lengths to make sure Jamie understands the situation— the other being that there’s no excuse for him to be a total dick about it just because his survival is at stake. As Hugh explains all that, he constantly prowls the rampart at the edge of the garage level, peering into the darkness for… well, something. And as he nears the end of his spiel, he does indeed spy what he’s looking for. There— does Jamie see that filthy-looking, nude woman doing the zombie trudge toward the garage entrance? That’s the thing he’s been talking about. Alarmingly, he allows the woman to get nearly within arm’s reach of the helpless Jamie before grabbing hold of the wheelchair and hustling her back down to his car. Then he drives her home, dumping her unceremoniously in the street beyond her front yard before racing away to wherever he came from.

Jamie’s parents call the cops, of course, but it doesn’t accomplish much. Hugh has just up and vanished, abandoning the crappy tenement he’d been renting off Eight Mile Road, and with it the entire false identity he used while courting Jamie. As for the story he told her after tying her up, the general consensus is that it was nothing but the raving of a lunatic. Even Jamie agrees on the surface, but the fact remains that the shambling woman was there, doing exactly what Hugh said her inexplicable pursuer would do. It’s only the next day at school, though, when Jamie becomes convinced that there really is something to the insane story. During a dull English class, she notices an old lady in a hospital gown wandering around the campus grounds; no one who passes by her reacts in any way, despite her obvious incongruousness. And truth be told, “wandering” is the wrong word for how the old lady is moving. Her progress may be slow and halting, but she’s unmistakably headed in one fixed direction— straight toward Jamie. The girl veritably bolts from the classroom, much to her teacher’s consternation, and seeks the aid and comfort of her sister and friends.

Kelly, Paul, and Yara are flummoxed to see Jamie behaving as if she now believes Hugh’s yarn about a supernatural stalker, but there’s no gainsaying the authenticity of her fear. Her two friends agree to sleep over at the Height house that night to keep an eye out for any trouble, but it happens that there’s a rather serious hole in their strategy. Whatever is now after Jamie is invisible to everyone but its current and former targets, so the other three kids are no help at all on lookout duty. All they can see is Jamie flipping out about somebody being in the house with them, and then running away down the street as fast as she can. They eventually catch up to her in a park somewhere (the thing, fortunately, does not), picking up along the way some assistance from Greg Hannigan (Daniel Zovatto from Beneath and Innocence), the boy who lives across the street.

Greg, like the others, remains agnostic about sexually transmitted demons, but he doesn’t hesitate to help Jamie track down Hugh the next day. A trip to the house he was renting (which is tricked out as a veritable fortress of homemade early warning systems and secret escape routes) turns up clues suggesting which high school he attended, and a visit to the office there reveals both his real name— Jeff— and his family’s address. Perhaps surprisingly or perhaps not, Jeff proves eager to cooperate with Jamie in any way he can, but his ability to help is limited. The fact is, everything he knows about the creature he sorted out by careful observation and a lot of trial and error. What it really is, where it really comes from, how to deal with it permanently— all that stuff is beyond his ken. Greg is the really valuable ally here, because his family owns a beach house way up on Lake Huron. At the rate Jamie’s nemesis moves, hiding out there should buy them plenty of time to brainstorm for battle plans.

There’s a pacing anomaly here that makes it difficult to say how successful that stalling tactic is. The ensuing action makes sense only if we assume that the movie has skipped a significant amount of time, but it doesn’t feel as if more than a few hours go by between the kids’ arrival at the shore and the next attack from the STD. Regardless, they certainly haven’t made any strategic headway by the time the thing catches up to them, but this latest confrontation has some positive results from their point of view. Most importantly, everyone but Greg experiences something that proves to them beyond a doubt the reality of Jamie’s monster. Kelly, Yara, and Paul all see Jamie hoisted by the hair from her beach chair, even though there shouldn’t be anything there to do the hoisting, and the boy actually has a brief physical tussle with the invisible force. Jamie and her friends also learn that the creature isn’t entirely impervious to injury. Shoot it in the head (Greg’s father keeps a loaded pistol in the boathouse), and it will go down, even if it gets up again a few seconds later. Finally, it appears that even direct attack from someone not the thing’s target will distract it only momentarily from its purpose. The creature knocks Paul down when he hits it with a chair, but it makes no effort to finish him off, returning instead to pursuing Jamie.

Jamie’s escape from the beach house is a matter of blind panic rather than clear thinking. She simply takes Greg’s car— no waiting for the others to come aboard— and speeds like a maniac until she loses control and drives into a cornfield. The next thing Jamie knows, she’s in a hospital far from home, with no idea how much time has elapsed since her flight from the lakeshore, and consequently no idea how far behind her the thing is likely to be. That uncertainty forces her to face at last the reality of what she must do. Whatever else happens, Jamie certainly can’t go on living like this. She’s got to pass the monster on to somebody else. But how? If she picked up a stranger to bang, she’d be no better than Hugh or Jeff or whatever his name is, even if she stuck around to explain the ground rules like he did. Jamie would really like to be better than that. Paul and Greg each know the score already, but can she really ask either of them to shoulder such a burden for her? Especially when she knows that Paul’s feelings for her have been drifting of late away from the strictly platonic? And if she did hand her nemesis off to a friend, which should it be, and on what basis should she make that decision?

I’m going to break this off a little earlier than usual in plot terms. We’re about halfway through the second act here, whereas I generally carry my synopses up to about the onset of the third. That’s partly because It Follows is still in theaters as I write this (dictating a light touch with regard to things that could be construed as spoilers), but the main issue is that the whole rest of the movie is basically a serial exploration of the alternatives already before Jamie. What happens when she pursues (or rejects pursuing) each approach inevitably effects how and whether she pursues the others, so I can’t really talk about any of them without at least implicitly giving away the whole game. What I will say is that no one ever suggests what immediately struck me as a vital tactical maneuver given the sexually transmitted demon’s invisibility to the uninfected, so to speak. Surely four of the five kids should fuck each other in succession so that the members of the party could effectively support each other in a fight against the creature, while leaving the fifth to verify potential threats, right? (“Hey, Yara— do you see that freaky-looking guy with the mismatched eyes and the prosthetic foot stumbling toward us?” “You mean the one who just came out of the alley? Yeah.” “Okay, cool. No, mister, I’m sorry. I don’t have any change on me.”) There’s every reason why they shouldn’t have tried that, though, because to do so would require an extraordinary lack of sexual hang-ups, and sexual hang-ups are exactly what It Follows is about just below the surface.

I do mean just below the surface, too. This movie’s status as a fable of sexual anxieties is sufficiently obvious that I don’t see much point in picking at it. However, I do feel compelled to commend writer/director David Robert Mitchell for making It Follows a parable of sexual ethics as well. It would have been the easiest thing in the world for a movie about a sexually transmitted demon to become nothing more than a thinly disguised purity screed, congratulating the survivors for their virginity and treating the monster as the proper punishment for harlots and satyrs (but mostly harlots, of course). Instead, though, this film assumes not only that it’s normal and natural for young people to have sex, but that there’s nothing innately wrong with that even when it leads to bad consequences. Rather than spinning yet another cautionary tale, Mitchell metaphorically explores the questions of what to do once you’ve already fucked someone you shouldn’t have, and of how to tell the difference beforehand next time. Note also that the sexually transmitted demon can be read as stand-in for plenty of stuff besides that other thing we usually abbreviate “STD.” It could just as well be an unplanned pregnancy, an unwanted reputation, an obsessed stalker, or anything else that’s hard to get rid of once the mistake has been made.

We do need to talk about the surface itself, though, because that’s where It Follows truly excels. It must be harder than it looks to match the technique of a film to its subject matter— otherwise it wouldn’t grab me so hard when I see it done well. The upshot for the characters here is that Jamie is never safe. Her nemesis is out there somewhere at all times, slowly but infallibly homing in on her. She can never allow herself a moment with her guard down, and must constantly keep aware of everything going on at the periphery of her environment. Mitchell quickly shows us that we have to be just as vigilant. A couple of low-blow jump scares early on is all it takes to convey the lesson, and once you’ve learned it, you can’t help noticing how Mitchell uses the full breadth of the widescreen frame to mount his monster attacks, or that there always seems to be somebody moving around in the background when Jamie is in a public place. Any one of those fuckers could be the monster, so you have to keep splitting your attention among the spatial layers of the action onscreen. It frays the nerves even before Jamie’s trip to the hospital, and there’s no respite that you can trust until the closing credits. Those who appreciate the more masochistic pleasures of horror cinema will understand that It Follows is on that account a movie to be cherished. Those who prefer their spook shows safely declawed are advised to look elsewhere for an evening’s entertainment.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact