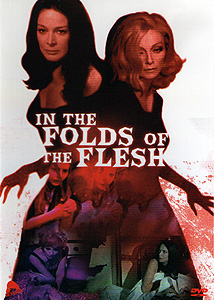

In the Folds of the Flesh/Nelle Pieghe della Carne (1970) -***

In the Folds of the Flesh/Nelle Pieghe della Carne (1970) -***

No, no— not those folds. (Although I admit that that was the first thing I thought of, too.) The folds in question here are the ones Sigmund Freud was talking about when he wrote, “What has been remains embedded in the brain, nestled in the folds of the flesh. Distorted, it conditions and subconsciously impels.” I can be certain of this because In the Folds of the Flesh helpfully begins its opening credits by quoting (and misspelling) that passage. And given that Freud is popularly associated with both mental illness and the idea that all of human behavior is explicable in terms of forbidden sexual impulses— incestuous impulses especially— I think we already have enough information to predict a great deal about how this little-seen and highly atypical giallo is going to conduct itself.

In the Folds of the Flesh starts brilliantly, maintains a fair level of competence until about the last 25 minutes, and then immolates itself on a pyre of astonishing stupidities. It’s really a very impressive turnaround, in its way. That brilliant beginning has wanted killer Pascal Gorriot (Fernando Sancho, from Return of the Blind Dead and Swamp of the Ravens) fleeing from the police through a remote seaside settlement. When he reaches the beach, Gorriot spies a small powerboat moored at the foot of a wooded ridge overlooked by what appears to be a villa converted from a medieval watchtower, and Pascal figures he’s found what he needs to give his pursuers the slip. Before he can reach the boat, however, a woman whom we will later come to know as Lucille (Eleonora Rossi Drago, from The Carpet of Horror and The Secret of Dorian Gray) fires up its engine and launches it out to sea unoccupied. Intrigued, Pascal follows Lucille up the ridge at a discreet distance, and from a hidden vantage point in the bushes, he watches her bury what appears to be a decapitated corpse. No sooner has Lucille completed this, well, undertaking than those cops who were on Pascal’s trail appear at her front gate. Somebody must have spotted Gorriot loping along the beach, because the officers inform Lucille that they have reason to believe their quarry is hiding out on her property. It ends up being a very narrow escape for Lucille, and no escape at all for Pascal.

Thirteen years go by. Lucille still lives in the watchtower villa, and the children we glimpsed briefly in the background during the corpse-burying prologue are there, too, although they’re all grown up now. The boy is Colin (Emilio Gutierrez Caba, from The Sweet Sound of Death and At the Service of Spanish Womanhood), Lucille’s son; the girl is Falesse (Octaman’s Anna Maria Pierangeli), but it won’t be at all clear for most of the film exactly what her relationship to the others is. I’ll be nice to you, though, and say up front that she’s technically the owner of the house, which belonged to her long-missing father, Andre (played in the numerous flashbacks by Giancarlo Sisti, from Gungala the Black Panther Girl and Nazi Love Camp 27), and that Lucille was Falesse’s nanny when she was a child. Those of you who suspect that it was Andre whom Lucille was burying in the garden that night thirteen years ago may be on to something. Anyway, this bunch is about to have a little family reunion, because a cousin of Andre’s named Michele (Alfredo Mayo, of Voodoo Black Exorcist and A Bell from Hell) is on his way for an unannounced visit. A second man, called Alex (Victor Alcazar, of It Happened at Nightmare Inn and Horror Rises from the Tomb), drops off Michele and his pet German shepherd, and drives away after a short, cryptic conversation about somebody by the name of Derek— let’s just say that it won’t take anybody too long to figure out that these guys are up to something. Nevertheless, only Colin gives any outward sign of suspicion; he probably has more reason for mistrust and resentment than either of the women. Certainly one can’t expect him to be elated at all the flirtatious attention that Michele lavishes on Falesse (whom any fool should be able to recognize as Colin’s lover), and beyond that, the visiting cousin’s dog immediately develops the irritating habits of pissing on the front steps and hassling Kiki and Kioka, the family’s two African gray vultures. While Falesse coos over the piece of jewelry made out of a live beetle that Michele gives her, and shows off the relics she and her family have dug up from the Etruscan cemetery beneath their basement, it’s Colin who notices the dog sniffing at a certain familiar patch of ground in the garden, and who kills it before it can reveal the considerably less ancient bones buried there. Surprisingly, however, Colin is not the one who kills Michele. That honor falls to Falesse, of all people, who lapses into a sort of trance when her cousin sneaks into her bedroom after writing a short letter to the aforementioned Derek, and begins rifling the girl’s drawers for who knows what reason. Evidently operating under the delusion that Michele is the long-dead Andre (who, if the distorted flashbacks may be taken at anything like face value, appears to have met his end while molesting his pubescent daughter), Falesse rises from her bed, produces a dagger from underneath her pillow, and strikes the old busybody down. Colin, we now learn, was watching the entire time, and he summons Lucille to help him take the body down to the basement for disposal in the same caustic bath they use to clean the organic crud off of their unearthed Etruscan artifacts.

You will remember, however, that Michele had an accomplice. Alex returns the next day (just after Lucille and Colin have finished feeding the last pieces of Michele into their big vat of protein-consuming green glop), and he immediately begins ingratiating himself to Falesse— do you perhaps get the feeling the other two members of the household spend a lot of their mornings disposing of men’s corpses? Falesse is even more open to Alex’s advances than she was to Michele’s, and Colin becomes rabidly, obnoxiously jealous. Then again, perhaps the romantic strife is a good thing for the family, since it seems to be having the effect of keeping Alex distracted from his efforts to figure out what really became of Michele. Oh, sure— Falesse might tell him that the other man was called away on unexpected business, but Alex recognizes the dog’s collar when he sees it draped over a hook on the outside basement door, so he has fair reason to suspect that something more sinister is up. Eventually, Alex gets Falesse into bed, but he is both faster and more on his guard than Michele had been the night before. When the girl goes into her murderous trance and pulls out her dagger once again, Alex catches her hand before she can complete the stab, and wrestles her into submission. This, by the way, involves snatching the blonde wig off of her head, leading us all to spend the next half-hour and change trying to figure out whether or not we’re supposed to be able to reconcile the jet-black locks thus revealed with the blonde hair of the juvenile Falesse in the flashbacks. The short version: it’s quite possibly the goofiest piece of foreshadowing ever. We’ll get to that later, though. In the meantime, Colin (once again perving on the goings-on in Falesse’s bedroom), steps in and helps his boss/girlfriend turn the tables on Alex. Off to the basement glop-bath once more!

Time out now for a curious interlude. Some middle-aged guy we’ve never seen before (and whose name does not appear in the credits despite this character’s central importance during the disastrous final act) stops in at a mental hospital on the “Bedlam, 70’s style” model, where a female psychiatrist (who isn’t credited, either) introduces him to a young blonde woman (also not credited, but I have at least some reason to believe that she might be The Sexual Revolution’s Maria Rosa Sclauzero). The man wants her released into his custody, and the doctor consents with what we are probably supposed to interpret as reluctance, but really looks more like an irresponsible lack of concern.

Now many of you have probably begun to fear at this point that the scenario set up by that wonderful opening scene is never going to materialize. After all, we’ve now had two outsiders come snooping around the villa, only to be unceremoniously dispatched without ever uncovering a thing. We can all relax, though, because guess who just got out of prison? That’s right— it’s our old buddy, Pascal Gorriot, and he remembers that night in the garden very, very well. He returns to the scene of his capture a day or two after Alex’s demise, where he describes to Lucille what he saw out behind her house and how he proposes to exploit it. Pascal figures his silence over the last thirteen years is worth about $100,000 to Lucille, and that another hundred grand ought to cover him keeping his mouth shut on the subject for the rest of his life. When Lucille objects that she has no idea what he’s talking about, Pascal takes her and the kids out back at gunpoint, and makes them dig up the flower bed where he saw her working on the night the cops got him; imagine his enraged astonishment when the excavation turns up the carcass of Michele’s dog instead! Gorriot is sure it was a human body he saw in that shallow grave, though, and he’s determined to get at it, even if that means making Lucille, Colin, and Falesse dig up the whole fucking garden. In between excavations, Pascal keeps himself amused by abusing his “hosts” in whatever ways strike his passing fancy, and I’d be tempted to interpret his part of the movie as a bid to cash in on The Last House on the Left, had In the Folds of the Flesh not been made two years earlier than the more famous film. Eventually, Lucille decides that she’s had enough, and inspired by her experiences as a teenager in a Nazi death camp (What?! Really?!), she gives Colin a couple of cyanide tablets to drop into Pascal’s bath by means of a booby trap involving the cuckoo clock above the tub. Exit Signore Gorriot, stage right.

Finally, along comes that uncredited guy from the asylum scene. Lucille doesn’t recognize him when he strides into the garden like he owns the place, but he claims to be none other than the vanished Andre. (Which, if true, would mean that he really does own it.) He explains away the radical change in his appearance as a combination of age and plastic surgery, then mentions that he’s now calling himself Derek. (Ah, yes…) Whoever was after him so avidly as to make him fake his death thirteen years back will never recognize him now, even if they were to meet face to face. Alright. So then who the hell was Lucille burying in the flower bed if not Andre? The movie will spend the entire final act explaining that— and then explaining it again, and then explaining it again, each explanation exposing the last as a lie. By the time it’s all over, we’ll see that Derek isn’t really Andre, that the man murdered in the prologue wasn’t really him either, that Falesse isn’t really Falesse, and that neither the real Falesse nor the fake one really committed that initial murder. Oh— and we’ll also see that Colin’s really been fucking his sister all this time, but somehow didn’t realize it.

That cascade of increasingly absurd concluding revelations would be enough to throw the self-destruct switch on In the Folds of the Flesh regardless of how it was handled, especially since it requires the last-minute introductions of several major characters whom we’ve never even heard of before (including Colin’s sister, Ester, and Lucille’s husband, Antoine [Luciano Catenacci, from Kill, Baby… Kill! and Short Night of the Glass Dolls]), but what really undoes the movie is the specific strategy that the filmmakers use to bring them to light. When I said that the whole final act is spent explaining what Lucille was doing in the garden that night, I meant it quite literally. In an orgy of exposition and counter-exposition outstripping any seen since perhaps The Unholy Night, one character after another tells their version of the story’s originating events. Fortunately, each retelling comes packaged with its own set of flashbacks, giving us a little something to do with our eyes. What makes this belly-flop of an ending so much more entertaining than The Unholy Night’s, or than the comparably botched conclusions of movies ranging from The Invisible Menace to Torso, is that despite certain similarities of detail, it is conceptually the direct opposite of the typical lousy murder-movie wrap-up. Most of the time, when a movie like this one goes off the rails in its final phase, it’s because of a frantic, last-minute scramble to tie up a mystery established early on, which at least notionally serves as the driving force of the plot. The new characters who appear out of nowhere will be fingered as the culprits; the contrived and implausibly elaborate scheme requiring lengthy explication will be that by which the victim was slain; the devolution into flashbacks and drawing-room jibber-jabber will be necessary because honest detective-work is beyond the writers’ abilities, or (especially in the case of a giallo) because the movie has been too busy with operatically staged murder scenes to have much attention left over for crime-solving. In the Folds of the Flesh, though, ends the way it does because it is being sold as a giallo— by definition a murder mystery with a horrific emphasis— yet after more than two thirds of the running time, there is still no worthwhile mystery to be solved. In order to meet its genre obligations, it must retroactively drape enigma and uncertainty over events that are perfectly straightforward and instantly comprehensible as they have been presented to us. It goes about its climactic business not just ineptly, but completely ass-backwards.

That would have been terribly disappointing had the ineptitude in question been anything less than awe-inspiring, for the first hour or so of In the Folds of the Flesh is very enjoyable on its own terms. It plays the Villainous Protagonist card adroitly, making an unexpected advantage of its weirdly episodic story structure. The prologue cues us to expect a clash between Pascal Gorriot and the inhabitants of the villa, and we naturally assume at first that the brawny and ruthless career criminal will have the upper hand when it happens. But then the fate of Michele forces us to reevaluate that assumption, and after Alex meets the same end, we begin to suspect that it’s Pascal who is getting in over his head. Before, I compared the Pascal episode to The Last House on the Left, but it also suggests to me how House on the Edge of the Park might have worked had we known up front that Alex and Ricky’s invitation to the party was the opening gambit in a vigilante trap. (That is to say, it works noticeably better than the House on the Edge of the Park that we actually got.) Meanwhile, the detour into Love Camp 7 territory represented by the flashback that accompanies Lucille’s “we’ll kill him with cyanide” spiel is exactly the sort of sheer lunacy that one looks for in an Italian horror film of this vintage, and seems all the more tastelessly impressive given that In the Folds of the Flesh came some four years before The Night Porter touched off the vogue for such things in Europe. For both good reasons and bad, I’m glad that In the Folds of the Flesh has finally been loosed on the unsuspecting American public.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact