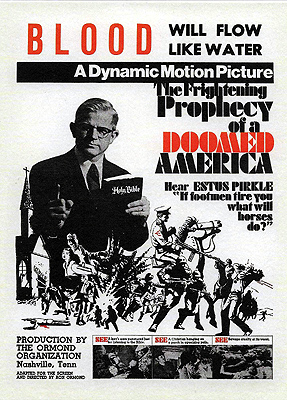

If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do? (1971) -**½

If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do? (1971) -**½

No way was a kid named Estus W. Pirkle ever going to grow up to be anything but a deranged fundamentalist preacher. Born in Georgia in 1930, Pirkle attended seminary in Fort Worth, and then bopped around the South for the remainder of his early adulthood before finally settling in New Albany, Mississippi, where he led the congregation of Locust Grove Baptist Church into error and darkness for 36 years. The 60’s and 70’s seem to have been Pirkle’s heyday. At the very least, that era afforded him the most exciting enemies against whom to do battle from the pulpit. Between the Sexual Revolution, the hedonistic hippy counterculture, educational reformers, and the Supreme Court taking the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment seriously for the first (and thus far only) time in American history, it was a target-rich environment. But the foe that riled up Estus W. Pirkle like no other was international communism— which he viewed less as a political or economic ideology than as a Satanic plot motivating and inspiring all the world’s other ills. What feels strange, though, from a 21st-century perspective, is that the pulpit was apparently the only place where Pirkle did battle. Conversion was his sole and invariable prescription for everything, as if he was incapable of understanding any issue except through the lens of personal and individual devotion to God. Incredibly, Pirkle steered so clear of politics in the ordinary sense that I can find no indication of him ever attempting to assert Divine support for Jim Crow segregation as so many other conservative, white, Southern preachers were doing in those days. (Either that put him decades ahead of the game with regard to knowing when to keep his big fucking mouth shut in public, or it constitutes one genuine bit of credit that we need to extend him, and I’m not at all sure which it really is.) That focus on getting right with God over taking action to influence the world can also be seen in Pirkle’s approach to preaching more generally. If conversion is what matters, then the proper role of the preacher is to run up the scoreboard with nominal changes of heart; it’s a waste of time and effort to engage in the kinds of hands-on pastorship that might change somebody’s life. Consequently, Pirkle was the sort of minister who liked to get his sermons printed up as pamphlets for dissemination on street corners. Later on, he took to recording them, and issuing them as vinyl LPs. And then, in 1971, he met Ron Ormond, and things got weird.

Ormond, with the aid of his wife, June, and his son, Tim, was an independent producer-director. After a bit of a false start in the trenches of 1940’s Poverty Row, he relaunched his career as his own man in the early 50’s, pioneering both burlesque movies and hicksploitation, while simultaneously keeping Lash La Rue, Hollywood’s drunkest, horniest has-been cowboy, in one last, shrinking corner of the limelight. Later, Ormond expanded into jungle movies, monster movies, and lurid melodramas about women in sex-related trouble, trading on the old trick of clothing salacious sensationalism in a g-string and pasties of concern for underreported social issues. His strangest sideline during the 50’s and 60’s, though, has to have been a series of books that he co-wrote with his good friend, Ormond McGill, on a variety of topics near the intersection of spirituality and the paranormal, including meditation, hypnosis, and psychic surgery. Ormond was also an amateur pilot, which got the whole family into trouble one day in 1967. On the way east for a personal appearance at a screening of The Girl from Tobacco Row, Ron crashed his little single-engine puddle-jumper into a farmer’s field on the outskirts of Nashville. Although Ormond managed to retain sufficient control of the doomed aircraft to prevent any fatalities, he and June were both seriously hurt; Tim, incredibly, emerged almost unscathed. It was a transformative experience for them all, albeit one that took a couple years before it really stuck. Although Ormond made one more of his increasingly Southern-fried schlock-o-ramas (the fantastically skuzzy The Exotic Ones) in 1968, he ultimately decided that God was trying to tell him something by letting him and his loved ones survive the crash. Ormond got out of the movie business, left Los Angeles, and moved to Nashville— not far, you’ll observe, from the site of his brush with death. Then, at the instigation of a mutual friend, he met Estus Pirkle, and realized just what the Almighty had in mind by saving him. Pirkle was doing a volume business harvesting souls for Jesus, right? And Ormond knew, as only a veteran sleaze-merchant can, the drawing power of the movie screen, didn’t he? Put the two men together, and it’s obvious what they had to do. Ormond was going back to work in his old field, only instead of making cheap, trashy exploitation movies, he’d henceforth make cheap, trashy exploitation movies for the Lord!

If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do? was the first of three such collaborations. The enigmatic title is a riff on the opening lines of Jeremiah 12:5— and if you’re thinking that sounds like the way Evangelical ministers construct their sermons, then you’ve already got some idea what’s coming. Yes, If Footmen Tire You was a sermon before it was a movie. It must have been one of Pirkle’s greatest hits, too, because it was released as both a pamphlet and a record album in the 60’s. Concerned as always for spiritual purity, and rightly wary of how it might be compromised in this new undertaking, Pirkle insisted on complete creative control, and the film therefore bears only the most tenuous resemblance to a conventional motion picture. (Legend has it that the preacher had never actually seen a movie before, so ominously did Hollywood’s reputation for sin precede it.) If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do? is part sketch show and part concert film. Pirkle delivers his oft-practiced lecture once again, his oratory frequently overlaying and occasionally interrupted by brief dramatizations of its salient points. And as befits a sermon riffing on a quote from Jeremiah, the thrust of Pirkle’s preaching is that by turning away from God, America is inviting Divine punishment in the form of invasion and conquest by the mighty and merciless hordes of communist Cuba.

Normally, this is the point in the review where I’d start synopsizing the first two acts or thereabouts of the movie’s narrative. I can’t do that here, though, because If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do? hasn’t really got one of those. Instead, we’ll see Pirkle preaching, whether in the pulpit of Locust Grove Baptist or in some other, similarly prosaic setting, and then the image will shift to some subset of his congregation acting out whatever tribulations the minister is threatening the United States of Apostasy with at the moment. These sequences can be surprisingly abstract, too, in counterintuitive ways that stem from the inexperienced and unsophisticated writer and cast trying to take metaphor and hyperbole literally. Maybe Ormond will manage to assert his directorial prerogative to transition into an actual, scripted scene after a little while, but it’s just as likely that Pirkle’s voiceover will jump the tracks to some other topic, forcing a return to the pulpit instead.

Nevertheless, the constant topical toggling between America led astray and the prophesied consequences thereof does have the effect of sorting the dramatizations into two broad categories, each of which operates in aggregate as something like a plot thread. On the one hand, we see rather a lot of a teenaged girl called Judy (Judy Creech), who flirts with damnation by drinking, carrying on with boys, listening to rock & roll, and scoffing at the danger hanging over her eternal soul. Judy’s behavior causes no end of anguish for her strangely elderly mother, and as the sermon builds, if you can call it that, toward the altar call (No, seriously. If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do? ends with an altar call!), the girl finds herself beset by intrusive thoughts of Mom’s heart giving out under the strain of her constant worrying. Then on the other hand, we get prophetic vignettes of New Albany overrun by Cuban soldiers whose commander (Cecil Scaiffe, one of the few professional actors in the cast, whom Ormond had used before in The Exotic Ones, and would use again in The Grim Reaper) devises one lurid cruelty after another in the hope of making the townspeople renounce God. (Wait— isn’t the whole point of this sermon supposed to be that they’ve already done that?) Then along the way, Pirkle takes time out to ride one or another of his personal hobby horses, condemning TV, drive-in theaters, miniskirts, “the liquor traffic,” and dancing. (Again, I’m completely serious. Cranky old bastard is still worked up about dancing in 1971.)

A lot of this stuff is an absolute scream. During a digression on the decline of American public education, Pirkle laments how the McGuffey Readers (the mainstay textbooks of American primary schools from 1836 until well into the 20th century, notable equally for their revolutionary pedagogical design and their overtly Presbyterian approach to moral instruction) had fallen out of favor in recent decades. But he segues into that complaint by saying that when his father was a child, schoolkids used to study “a masterpiece of a book,” in tones implying that he has in mind something a great deal more elevated than a simple primer— the Bible, probably, or at least some text from the founding era of the American republic. His rant on sex ed classes transitions into the shortest of the scripted dramatizations, in which a lanky weirdo identified as “Comrade Teacher” (Wes Saunders) extols the virtues of premarital sex before cuing up a discussion of “the seven erotic zones of passion in every woman.” That segment cuts off before Comrade Teacher can get properly started, which is really too bad; I suspect a lot of the target audience could have used a few pointers on the subject. And Judy’s guilty fantasy of her mom’s funeral shows the deceased lying in her coffin wearing the same hairnet that always adorned her head in life.

It’s the Cuban Conquest segments that reveal Ron Ormond’s influence, however— although Pirkle was by all accounts pleased with them, given his intention of scaring his audience back onto the straight-and-narrow. If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do? is often described as a Fundamentalist Christian horror movie, and although that’s extremely misleading, there’s an argument to be made for it on the basis of how Ormond handles the torture and brutality visited on New Albany by the communist invaders. I’ve never seen so many piles of dead, bloody children in a single film before! Mind you, Ormond lays it on so thick that the movie quickly blows past legitimate shock into the realm of the merely ludicrous. The beheading that climaxes the final scene before the concluding altar call in particular is like something out of The Corpse Grinders or The Undertaker and His Pals. The cheap but over-the-top gore is further undercut by the moustache-twirling villainy of the Cubans— and indeed by the mere fact that they’re Cubans and not Russians, Chinese, or some imaginary faction of homegrown communist revolutionaries. Like, get a load of the scene in which a teenaged boy tries to fob off the commissar collecting loyalty oaths in his neighborhood with a bogus conversion to Marxism, only to have the commissar demand that he prove his devotion to the red cause by shooting his mother. Perhaps even more self-defeatingly outrageous is another vignette in which a Cuban agent destroys the faith of a gaggle of schoolboys by demonstrating that praying to Jesus for candy won’t get them any, but asking for it in the name of Fidel Castro will.

You will not be surprised, I imagine, to learn that If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do? was never really intended to play in regular movie theaters, although it may have done so on occasion. The film’s natural habitat was instead in churches of like-minded congregations. Incredibly, it was still in circulation on that circuit at least as recently as the 1990’s, the end of the Cold War and the utter irrelevance of its cultural references notwithstanding. Notice, too, that it was irrelevant by then not just in terms of its obsolete bogeymen, but in terms of how the Evangelical subculture that it notionally represents had evolved since 1971. Most conspicuously, the movie was made most of a decade before the ideological realignment in Protestant religious conservatism that made opposition to abortion the core tenet of the faith, and Pirkle simply never mentions the subject at all. Nor does the Rapture ever come up, no matter how often Pirkle strays into End Times preaching. Again, it’s a matter of timing. In 1971, Post-Millennial Dispensationalism was still the dominant mode of Fundamentalist eschatology. Pirkle’s successors might flatter themselves that the right kind of Christian (themselves, of course) would receive “Get Out of Tribulation Free” cards from God, but the congregants at Locust Grove Baptist back then were taught that the faithful were going to have to suffer through the reign of the Antichrist right alongside the rest of us. That sort of thing makes it a doubly disorienting experience to watch If Footmen Tire You, What Will Horses Do? today. The film opens a window not only into a strange and sometimes disturbing subculture, but into a form of it that no longer exists.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact