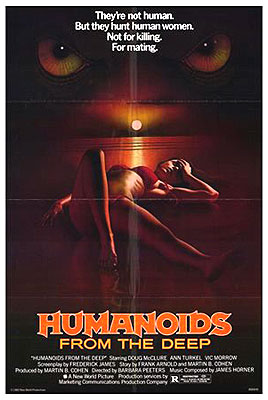

Humanoids from the Deep / Monster (1980) ***½

Humanoids from the Deep / Monster (1980) ***½

Listen up, ‘cause El Santo is about to impart to you some more of his hard-won bad movie wisdom. This message is for the ladies, on the off chance that anyone reading this actually meets that description. You ready? Okay. Stay the hell away from gill-men. Gill-men are some horny sons of bitches, and they have a well-documented weakness for chicks in bikinis. You laugh, but I know what I’m talking about. Going all the way back to the Creature from the Black Lagoon, nine out of ten gill-men have only one thing on their fishy little minds-- they want to fuck, and they want to fuck good-looking human women in particular. So today, in an effort to get to the bottom of this curious phenomenon, we’re going to have a look at the original Humanoids from the Deep, my favorite horny gill-man movie of all time, and the only such film with the nerve to try to answer the burning question of why on Earth a mutated man-fish would want a hot human piece of ass, anyway.

This movie is also fascinating for the way that it somehow manages to squeeze nearly every hoary bad movie cliche imaginable into a mere 80 minutes, while simultaneously offering a step-by-step guide on how to make both a 70’s eco-horror flick and an 80’s body-count movie. By the time this is over, we’ll have seen evil capitalists, righteous Indians, concerned scientists, brutal rednecks, horny teenagers taking off their clothes and dying, excessively mutagenic toxic waste, ridiculous pseudo-science, boyfriends who don’t hear something sneaking around while they try to get into their girls’ pants, and municipal celebrations ruined by gate-crashing monsters. We’ll see a variation on the zombie-siege theme, dogs and children who can detect evil as if by radar, and false scares provided by falling dishes, ringing telephones, asshole boyfriends, and spring-loaded cats. There will be gratuitous shower scenes, a helpful plot-specific radio station, and an amphibious version of the killer hiding in the back seat of the car. We’ll even get to see a matricidal monster-birth, a la Alien. You may scoff, but if you ask me, it takes real talent to pack such a huge roster of time-honored cliches into so short a film in such a way that they not only seem properly placed, but also serve to keep the plot moving at a blitzkrieg pace.

The film takes place in the small New England fishing village of Noyo, which is set to become the home of a shiny new Canco salmon cannery. The townspeople are, for the most part, excited by this development, which promises to revive the local economy. The annual salmon catch has been slipping in recent years, you see, and Canco’s industrial fishing techniques look like the answer to all Noyo’s problems. Or at any rate, they do if you’re a moron. As it happens, there is exactly one non-moron in all of Noyo, and his name is Johnny Eagles (Anthony Penya, whom we’ll see again in Megaforce and The Running Man). As you may have gathered from his surname, Johnny Eagles is our Righteous Indian, and he wants Canco to stay the hell away from Noyo, rightly believing that their methods will drive the already threatened salmon population to extinction in a matter of years. But his warnings invariably fall on deaf ears, because the most powerful man in Noyo, Hank Slattery (Vic Morrow, from 1990: The Bronx Warriors and Great White), is also the leader of the Brutal Redneck faction. And because he leads the Brutal Rednecks, Hank naturally suspects Johnny Eagles is at work when strange and nasty things begin to happen in and around Noyo. First, a small salmon boat explodes out in the bay. We know that the explosion was caused by an unfortunate chain of accidents (leaking oil-pump, spilled gasoline on the deck, man overboard, something big and cantankerous caught in the salmon net, a flare gun fired at an inopportune moment), but Hank thinks it was sabotage. Later, when something kills all of Noyo’s watchdogs except for Johnny’s, Hank again jumps to the conclusion that Johnny is using terror tactics to oppose the cannery’s arrival-- nobody wants to set up business in a town full of bomb-throwers, after all.

Fortunately for Johnny, though, there is another man in the town capable of acting as the voice of reason. This man is Jim Hill (Doug McClure, from Warlords of Atlantis and The Land that Time Forgot), and despite the fact that his dog was among those killed (he and his wife Carol [Cindy Weintraub, from The Prowler] found its skinned and mangled carcass out on the beach the same morning that Hank and his men discovered their dead dogs on the docks), he has the sense to see that one Indian vs. several dozen dogs is not exactly good odds for the Indian. Hill and his young protege, Tommy, bail Eagles out when Hank’s cronies jump him at the first night of the annual Salmon Festival, at which Canco’s president (who shockingly survives the movie, despite his role as the Evil Capitalist) gives a speech promising all sorts of good things for the town. This scene is also important in that it introduces our Concerned Scientist, Dr. Susan Drake (Ann Turkel, of The Ravagers). She works for Canco, and it was she that perfected the company’s radical new technique for making industrial fishing an ecologically sustainable enterprise. Using a remarkable genetic treatment called DNA-5, Drake has found a way to make salmon grow larger, faster, and twice as plentiful as they would in nature, allowing their populations to withstand the staggering rates of attrition that come with industrialized fishing.

But we all know what happens when scientists go messing with the genomes of lower life forms, so we make the connection instantly between Drake’s experiments and the big slimy things that we’ve glimpsed killing dogs, frightening children, and fighting their way out of fishing nets. And it also comes as no surprise to us when they start going after humans a few scenes after Canco Man makes his pitch. That the human victims are disproportionately female is also only to be expected, because those brief glimpses we’ve been catching since the very first scene (to say nothing of the movie’s title) have been enough to tell us that Noyo’s big problem is a gill-man infestation. To the film’s great credit, it wastes no time at all in showing us a gill-man in all its toothy, flipper-bedecked glory after establishing the monsters’ obvious origin. This first gill-man wades out onto the beach one afternoon to kill Mullet-Boy (whom we’ve been seeing off and on for some time) and rape his bikini-clad girlfriend. Almost immediately thereafter (in movie terms-- I think it’s really supposed to happen later that night), another gill-man attacks a conjugating couple on the beach, tearing open their tent, killing the boy, and chasing his jiggling, nude girlfriend several hundred yards up the beach before catching and raping her as well. (My favorite thing about this scene: The boy is a ventriloquist. Watch the dummy’s eyes as the gill-man rips his way into the tent.)

Then, another bunch of gill-men put in an appearance at the home of Johnny Eagles. Our Righteous Indian has not been having a good week. Not only did he get beaten up by Hank’s rednecks the night before, the sons of bitches came by only a few minutes before the gill-man attack and blew up his house with what has to be the most powerful Molotov cocktail ever made. He had been talking over the likely environmental impact of the cannery with Tommy and his girlfriend Linda at the time, so at least it looks like he’ll have witnesses to Hank’s terrorism, but alas, both Tommy and Linda get worked over pretty thoroughly by the gill-men. Tommy survives, but just barely. Linda, on the other hand, is set upon by a gill-man hiding in the bed of Johnny’s truck as she attempts to go for help, and ends up driving the truck off a bridge in her efforts to shake the monster loose. Hey, at least she didn’t get raped by a fish that way...

With so large a proportion of our cast thus eliminated, it is clearly time for Jim Hill and Dr. Drake to step up to the plate and take control of the situation. This they do after having a look around the ruins of Johnny’s cabin. Drake clearly knows more than she’s telling as she pokes around the wreckage, and the sketch she makes of the monsters from Johnny’s description is just a little too accurate for comfort. Then she suggests they go out to the bay to look for the creatures’ lair (they’re obviously too big for the food supply upstream), and that suggestion leads to a pair of important discoveries. First, Hill, Drake, and Johnny do, in fact, find a gill-man nest in a sea cave in the cliffs overlooking the bay. Second, after killing the half-dozen or so monsters living there (they take about five shots each from a hunting rifle before going down), Drake notices Mullet-Boy’s girlfriend (Peggy, her name turns out to be) mostly buried under a blanket of kelp and mussel shells. They grab Peggy and a gill-man, take the girl to the hospital, and take the monster back to Drake’s lab.

Clearly, somebody has a lot of explaining to do, and at last, that explanation is forthcoming. Drake, it turns out, strongly suspected something like this might happen as a result of her experiments. Her Canco bosses were, of course, not interested in anything but their profit margins, so they hushed her up and had her keep working. But when several thousand DNA-5-treated salmon somehow escaped from the lab, Drake really began to worry. DNA-5’s effects on the salmon themselves were well understood, but what might the chemical do to an organism that ate those salmon? In particular, what might happen if a more primitive fish, whose evolution had, for whatever reason, been arrested early in its phylogenic development-- a coelacanth for instance-- were to eat the treated salmon? Mightn’t the DNA-5 kick that creature’s suspended evolution into overdrive, producing a beast the likes of which the Earth had never seen before? Nevermind the fact that coelacanths live in the waters around Madagascar, while Canco’s new operation is poised to set up shop in Maine or some such place (and while we’re at it, nevermind that “coelacanth” is pronounced “SEE-la-canth” and not “koala-canth”)-- Dr. Drake’s apocalyptic predictions have proven to be right on the money. Worse still, this new species seems to have developed a taste for speedy evolution-- the gill-men’s decidedly icky sexual interest in human women stems from a subconscious desire to improve their genome by importing genes from more advanced species!

All of which makes the outlook for the rest of the salmon festival distinctly grim. Sure enough, the gill-men crash the party en masse, killing or raping everyone they can get their scaly, webbed hands on in one of the finest horror-movie climaxes of the 1980’s. Jim, Drake, and Johnny show up in time to help fight the monsters, and Hank’s mob of Brutal Rednecks makes itself useful at last by forming an anti-gill-man posse, but the ending of Humanoids from the Deep is far from conclusive. Not only is there no assurance that all the gill-men have been destroyed, but Peggy’s fate, as revealed in the movie’s it’s-not-over-yet epilogue, raises the issue of what became of the other girls who were raped and kidnapped by the monsters.

The great thing about Humanoids from the Deep is the way in which it manages to be exploitative and sleazy and cliche-ridden on the one hand, and engaging and occasionally even thought-provoking on the other. The nastiness quotient here is high enough to satisfy even a long-time fan of Italian horror flicks (we are talking about a movie in which scads of women are raped by fucking fish, you realize), and the film is loaded with gore, fantastic slimy monsters, and purely gratuitous nudity, but Humanoids from the Deep also works on a second, almost satiric level. I have a hard time believing that a single movie could employ absolutely every bad movie cliche in the book by accident, and I find it equally hard to believe that the film’s exploration of the usually unstated implications of the ever-popular theme of ghastly monsters being smitten by interspecies infatuation could have happened unintentionally. And yet few, if any, reviewers seem to have given the subject any thought when they turned their attention to Humanoids from the Deep. My guess is that this is due to the movie’s completely straight-faced approach; it was clearly designed to work as an exploitation flick first and foremost, and there can be no question that it is a resounding success on that score-- at least if you measure an exploitation movie’s success by its power to shock and offend. But I seriously think that more is going on here than straight-up exploitation, that the filmmakers were simultaneously using the established conventions of exploitation cinema to take a good, hard look at the essential foolishness of those very conventions. Maybe I’m wrong-- Roger Corman was ultimately in charge of this flick, after all-- but I honestly believe that Humanoids from the Deep is one of those rare cheap horror films that is just as rewarding to watch with your brain turned on as it is with it turned off.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact