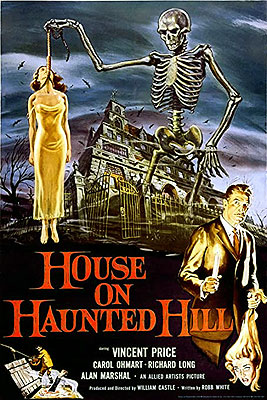

The House on Haunted Hill (1958) ****

The House on Haunted Hill (1958) ****

After The Tingler, The House on Haunted Hill is probably the movie for which William Castle is best remembered. It is also quite possibly the best film he ever made. This was fairly early in Castle’s gimmick-horror period, and The House on Haunted Hill positively buzzes with the director’s exuberance for his newly-entered field. You can scarcely blame the man-- say what you want about this film, or about 13 Ghosts or Mr. Sardonicus, but flicks like these are a hell of a lot more fun to watch (and must have been a hell of a lot more fun to make, too) than the tedious, low-budget Westerns that had been Castle’s primary stock-in-trade previously.

The setup is certainly nothing you haven’t heard before, but Castle’s put enough of his own spin on it to keep things interesting. For reasons that are shrouded in mystery, an eccentric millionaire named Frederick Loren (Vincent Price, in one of the very best roles of his lengthy career) has rented out a huge, isolated mansion that is reputed to be haunted by a veritable battalion of vengeful ghosts. (In exterior shots, the haunted mansion is stood in for by the Ennis-Brown house, a hideous Frank Lloyd Wright design which looks more like a futuristic prison than a place where people might voluntarily live.) He then invites five people whom he has never met face-to-face to stay in the mansion for an all-night party. Each guest will receive $10,000 if they last through until morning-- the catch being that the only door leading out of the place will be locked at midnight, trapping anyone who hasn’t chickened out yet inside. The guest list is as follows: Watson Pritchard (Elisha Cook Jr., whom we’ve seen before in small roles in The Haunted Palace and Blacula) is the owner of the mansion, and the only one of the characters to have set foot in it before. He did so only once, and he claims the experience nearly killed him. Pritchard needs the money because he’s a drunk and a wastrel. Dr. David Trent (Alan Marshal, from the 1939 version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame) is a blowhard psychiatrist with a bug up his ass for hysteria. He thinks it will benefit his research to observe a group of people hanging out in a supposedly haunted house-- with all those “ghosts” about, surely somebody is going to have a fit of hysterics before the night is through. Lance Schroeder (Richard Long, of Cult of the Cobra) is an air force test pilot. Loren seems to think it will be interesting to see how a man whose job requires him to risk his life daily will hold up when threatened by something less immediately understandable than a plane crash. Nora Manning (Carolyn Craig, who would end up on the cast of “General Hospital”) works as a secretary for one of Loren’s many companies. She probably needs the $10,000 more than anyone, as she has an entire family to support on her meager salary. Finally, Ruth Bridges (Julie Mitchum) is a snooty gossip columnist. Her thinking is that the experience will give her something new and unique to write about, though I’m sure her thousands of dollars’ worth of gambling debts have something to do with her presence at the house too.

If you’re hoping for an explanation of Loren’s real motives, you’ve come to the wrong place. The movie’s designed to keep you guessing about that until the very last scene, and I’m sure as fuck not going to give anything that important away-- not about a movie this good, at least. All I’ll say is that he tells his guests that his wife, Annabelle (Carol Ohmart, of Spider Baby, or The Maddest Story Ever Told), put him up to it. Annabelle, however, begs to differ. In fact, she doesn’t even want to attend the party. Clearly something is going on between the Lorens, and it will gradually come out that each spouse thinks the other one is trying to kill them. And as it happens, both Frederick and Annabelle have firm grounding for their suspicions: Annabelle once tried to poison her husband, and all three of Frederick’s previous wives died young under questionable circumstances.

So when the weirdness begins (which it does with admirable dispatch), the question becomes, is what we’re seeing the activity of genuine ghosts, or is one of the Lorens orchestrating the whole business in an attempt to do away with the other? And if it’s the latter, which one is the perpetrator, and which is the intended victim? Or are they both out to get each other? Hell, for that matter, we ought not to rule out the possibility that the Lorens are trying to kill each other at the same time that the mansion’s real live (okay, fine-- dead) ghosts are doing the same! Whichever way you want it, one thing is clear-- someone or something really is trying to kill somebody. As for the nature of that weirdness I mentioned, we’ve got quite a list on our hands. We’re talking falling chandeliers, bleeding ceilings, vats full of concentrated acid hidden in the cellar floor, severed heads appearing in suitcases, apparitions and secret passages and people getting hung in stairwells. Basically everything you need for an old-fashioned haunted house movie is here, and all of it is interwoven so well that it becomes difficult to say much of anything about the course of the story without giving something important away.

But the best thing about The House on Haunted Hill really has relatively little to do with the story per se. Indeed, if you were to turn a critical eye on the script, you would see that, for all the well-oiled grace with which it comports itself, it is absolutely riddled with holes and inconsistencies. But to look at The House on Haunted Hill in that way is to miss the point almost entirely. This movie is designed to do one thing-- scare the living shit out of the kids who came to see it at the Saturday matinee-- and there can be no question that it is very well designed indeed for that purpose. In fact, this movie scared my father clear out of the theater when he first saw it at about the age of seven. The gimmick, the famous Emergo, seems particularly geared to a kid’s way of thinking. Near the end of the film, one of the characters is chased around in the basement by a walking skeleton. While this was going on, a casket mounted above the screen would pop open, and a life-sized plastic skeleton would glide out over the audience on a pulley-driven wire. Just try to picture how this would have looked to your nine-year-old self, the kid who (if you were anything like me) thought that skeletons were just about the creepiest things in the world. The really amazing thing, the thing that makes The House on Haunted Hill so wonderful, is that, while you’re watching it, you don’t have to try picturing it. Watching this flick, in and of itself, will make you remember what it was like to see through the eyes of a child, and is even capable of forcing your perceptions back into that long-forgotten mode of uncomplicated immediacy. It did it to me, and I was already well along the road to becoming a cynical old bastard when I was in second grade! The spell only lasts for the 75 minutes or so that you’ll spend in front of the screen, but even that is a much longer return to childhood than most adults will ever get. Such an experience is worth many times the time and effort you’ll have to invest in tracking down a copy of The House on Haunted Hill.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact