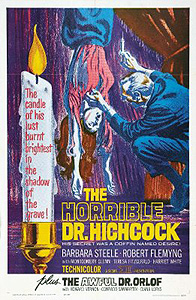

The Horrible Dr. Hichcock / The Horrible Secret of Dr. Hichcock / The Terrible Secret of Dr. Hichcock / The Secret of Dr. Hichcock / The Terror of Dr. Hichcock / Raptus / L’Orrible Segreto del Dottor Hichcock (1962/1964) ***½

The Horrible Dr. Hichcock / The Horrible Secret of Dr. Hichcock / The Terrible Secret of Dr. Hichcock / The Secret of Dr. Hichcock / The Terror of Dr. Hichcock / Raptus / L’Orrible Segreto del Dottor Hichcock (1962/1964) ***½

Like many horror movie fans, I admire a filmmaker who is willing to court disaster by pushing the bounds of good taste. This is doubly true in the case of those who know how to sneak something really twisted right under the noses of whatever organization is responsible for maintaining those bounds in their part of the world. Thus it is that director Riccardo Freda and screenwriter Julyan Perry have earned a salute from me with The Horrible Dr. Hichcock/L’Orrible Segreto del Dottor Hichcock. Seriously— imagine the nerve it would take to make a movie about necrophilia in 1962, even in Italy!

Letting us know immediately what we’re in for, The Horrible Dr. Hichcock starts off with a man whose face we don’t get to see cold-cocking a grave-digger working the night shift and then jumping into the coffin to feel up the lovely young corpse the poor bastard was trying to bury. Cut then to a hospital operating room, in which Dr. Bernard Hichcock (Robert Flemyng, from Thin Air and The Vampire Beast Craves Blood) is using an experimental new anesthetic on one of his patients. The operation proves successful, and both Hichcock and his assistant, Dr. Kurt Lang (Silvano Tranquilli, of So Naked, So Dead and The Pumaman), attribute the bulk of that success to the efficacy of the chemical. Both men then leave the hospital, bound ultimately for the Hichcock mansion, where the surgeon’s wife, Margaretha (The Giants of Thessaly’s Maria Teresa Vianello), is throwing a party that evening.

In case you had any doubts as to the identity of the corpse-fondler from the first scene, they are about to be dispelled. After arriving at home to find Margaretha’s party in full swing, Hichcock sneaks up to his bedroom. He instructs his maid, Martha (Harriet Medin, from Blood and Black Lace and The Whip and the Body), to tell his wife that he’s turning in for the night. Martha needn’t even say anything, as it happens; she just goes downstairs and shoots Margaretha a look from across the room, and the other woman immediately stops playing the piano, tells her guests that she is tired, and sees them all out the door. She then goes upstairs and meets her husband, not in his room, but in a sumptuously appointed chamber that opens directly onto the main staircase. As Margaretha lies down on the canopy bed, smiling winsomely at him, the doctor opens up a swank wooden case, from which he extracts a little glass vial and a horrifically huge syringe. Hichcock fills the needle with the vial’s contents, and injects his wife. Once Margaretha is peacefully unconscious, the doctor climbs into bed with her.

You get the feeling that’s something of a regular occurrence, too. Indeed, the Hichcocks are at it again the following night, but events progress a little bit differently this time. For some reason, Hichcock gives Margaretha a double dose of anesthetic, and under circumstances which make it clear that this stronger injection is entirely deliberate. So you have to wonder why the doctor seems so surprised when his wife goes into convulsions and dies as a consequence. I mean, Hichcock’s a practicing surgeon. Not only that, he invented the anesthetic he uses on Margaretha himself— he has to have some idea what an unsafe dosage looks like! But Hichcock is indeed shocked by his wife’s death, which sinks him into so deep a depression that he moves out of the mansion after burying her in a crypt converted from his backyard laboratory, leaving the place in Martha’s care.

Twelve years later, Hichcock returns to the old homestead. A lot has clearly happened to the man in that time, not the least of it his marriage to a woman half his age, by the name of Cynthia (Barbara Steele, from The Pit and the Pendulum and Nightmare Castle). Cynthia was evidently a patient of his at some point (I guess there was no such thing yet as a canon of ethics in 1885), and though the script initially seems to imply that he saw her in a psychiatric capacity, other rather more disturbing possibilities will probably come to mind if you think about it long enough. In any event, Cynthia is still very high-strung, and the decrepit condition in which she and her husband find the mansion upon their arrival gives her a four-alarm case of the willies. Martha doesn’t help any with her thinly veiled hostility toward her employer’s new wife, while the revelation that the maid’s insane sister is living in the house too— and will be for at least another couple of days— is, if anything, even worse. But oddly enough, what seems to creep Cynthia out the most is all the musty old paintings of Margaretha that are still hanging on the mansion’s walls.

Actually, let me amend that— Cynthia finds the paintings the creepiest thing about her new home at first. When she realizes that somebody is sneaking around the mansion with the obvious aim of getting at her while she’s asleep or otherwise incapacitated, that becomes the creepiest part of her life at Chez Hichcock. And it starts to seem even scarier after Cynthia hears from Martha that her mad sister has already been packed off to an asylum. Bernard, of course, thinks it’s just her old nervous affliction coming back. Dr. Lang thinks Cynthia’s real problem is that Hichcock neglects her. But Cynthia is not about to be persuaded that it’s all in her mind, and she starts doing some snooping of her own. Eventually, she discovers that Martha’s sister hasn’t gone anywhere after all, and she tells her husband about the maid’s suspicious deception straight away. But— and I'm sure most of you already see this coming— there’s more to the situation than that. Martha has no sister! The woman she’s been caring for up in the servants’ loft is none other than Margaretha Hichcock! Apparently that overdose Bernard gave her wasn’t lethal, but merely put her into a deep coma. Martha, while looking after the mansion, discovered what really happened and rescued the other woman from her tomb. And now, for mysterious reasons of her own, she’s been keeping Margaretha’s survival a secret— at least until Hichcock happens to see her out in the garden one night. With Margaretha back in the picture, Cynthia understandably seems a whole lot less attractive than she used to, and the other two Hichcocks begin looking for ways to get rid of her. Finally, it occurs to the doctor that his new wife might be useful as a source of raw materials for repairing his old wife’s looks, which are now a bit the worse for wear from her efforts to escape her coffin...

The most frustrating feature of The Horrible Dr. Hichcock is also the source from which much of its fascination springs. Not a single piece of anyone’s motivations is ever explained. We never do learn whether Hichcock’s poisoning of his wife was an accident or whether the doctor was hoping to make her seem just a little bit deader. We never learn why Martha waited more than twelve years to reveal to her boss that Margaretha was alive after all (it can hardly be because she was jealous or disapproving of their relationship, since we see her actively colluding with it early on). And of the greatest importance, we never get even the faintest hint of what benefit Margaretha could possibly derive from her accommodation of her husband's kink. She is obviously a willing— indeed eager— participant, but it’s hard to imagine what pleasure a woman could take in having sex while unconscious. And there doesn’t seem to be any sort of give-and-take going on, either, as no indication ever surfaces that the Hichcocks ever have sex any other way. Hell, Bernard never so much as touches Margaretha while she’s conscious!

Meanwhile, what about Cynthia? To a great extent, it appears that she is the centerpiece of Hichcock’s efforts to go straight, as it were. She looks entirely unlike Margaretha, she clearly doesn’t share her husband’s perversion, and he met her while far away from the old house. Not only that, we also see that Hichcock has entirely foresworn the use of his experimental anesthetic, even in its intended function. In fact, one of his later patients actually dies because of Hichcock’s refusal to use it on her. But consider: Hichcock cheats on Cynthia. More to the point, he cheats on Cynthia with corpses to whom she bears a striking resemblance, including that of the girl who died on his operating table when the Hichcock anesthetic could have saved her life. And given that Cynthia also looks like the corpse Hichcock molested in the cemetery in the opening scene— while Margaretha was still alive, I might add— it seems to me that there’s more to Bernard’s selection of Cynthia as his second wife than meets the eye. Remember when I said there was a more disturbing interpretation of Cynthia’s having been a patient of her future husband’s than the already pretty icky violation-of-psychiatric-ethics angle? Well how about this— whoever said Hichcock was Cynthia’s psychiatrist? There’s nothing else in the movie to suggest that the doctor is anything but a surgeon. What if Hichcock met Cynthia while she was on the operating table, unconscious, looking for all the world like that pretty, dead brunette from the first scene? What if Hichcock came into her room at the hospital after he was done, but before the drugs had worn off, and took advantage of Cynthia? What if all this time, he’s just been looking for the perfect opportunity to introduce her to the way he likes it?

The truly remarkable thing is that there really were explanations for much of this stuff written into the original screenplay. But as the production fell further and further behind schedule, Freda attempted to make up for lost time by simply cutting all of the scenes in which those explanations came out. When you bear in mind the miserably low quality of the writing in most European horror movies, it seems likely that whatever motivations Julyan Perry devised for his characters would have sounded awfully stupid had we been made privy to them. So in all probability, Freda's seemingly ill-considered time-saving measure turned The Horrible Dr. Hichcock into a much better, more engaging movie than it would have been had it followed the original script. And that, my friends, is at least as perverse as anything Bernard Hichcock does for fun.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact