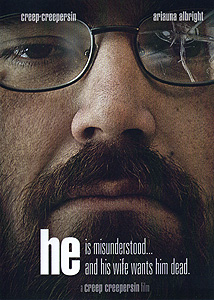

He (2009) *½

He (2009) *½

So far as I can discern, He was Creep Creepersin’s third feature-length movie. At the very least, it came extremely close to the beginning of his career as a maker of such things. That’s a point that bears dwelling on, because for all its faults, He displays a level of creative ambition that I normally associate with much more mature filmmakers— either that or with maverick geniuses too crazy to recognize the scale of the challenge they’ve set for themselves. Creepersin is no maverick genius, and the challenge of He was indeed a bit beyond his capabilities at this stage of his development. Nevertheless, it impresses the hell out of me that he had the moxie so early on to attempt something that might best be described as Eraserhead with a sense of humor.

We never learn the main character’s name, but he (Creepersin himself, whose other turns in front of the camera include Vampire Boys and OC Babes and the Slasher of Zombietown) is kind of a loser. He’s been out of work for far too long, the life of a suburban homeowner leaves him deeply dissatisfied, and his marriage is unmistakably on the skids. His wife (Ariauna Albright, from The Dead Hate the Living and Horrorvision) is just as unhappy as he is— not least because of their persistent inability to get her pregnant— and they’ve each come to blame the other for their mutual predicament. This is the story, if you can call it that, of the weekend when he figures out that the relationship is beyond saving, and has a nervous breakdown.

The gimmick is that everything in He is purely subjective, whether it represents his point of view or hers, and both of these people are in the process of cracking up (although the man is obviously further along in that department than the woman). Nothing we see or hear represents anything like external reality; it’s all filtered through the hostility, insecurity, and fear of one major character or the other. Whenever anyone speaks, what comes out is not their actual words, but rather the subtext (almost invariably negative) that the listener reads into the utterance. For instance, at a barbecue to which the wife has invited what I take to be her friends from work, one of the guests (Ron Hooker) engages the husband in small talk over the grill. What starts off as the usual “what do you do for a living?” bullshit rapidly segues into the guest casting cheerful aspersions on his host’s adequacy at the manly art of outdoor cooking. On another occasion, a conversation between the main characters over a job opportunity for him concludes with her saying, “Maybe this new job will have health insurance, so you can finally find out what’s wrong with your stupid sperm!” Scenes shown from her perspective, meanwhile, emphasize beyond any sane proportion the things she finds most annoying about him— his tuneless humming, his slovenly chewing, his childishly appalling taste in just about everything— and circle back obsessively to her fantasies about killing him or having him killed. My favorite example of the latter is the crossword puzzle with clues like, “If you had a knife, you would ____ him.” Sometimes, He will even shift points of view in mid-scene, as when the couple are fighting over some art that he wants to hang in the living room, and the picture in question changes back and forth between how it looks to him and how it looks to her.

That’s just the beginning of He’s surrealism, though. Like Eraserhead, He is full of characters who don’t actually exist (or at any rate, who don’t exist in the form we are shown), but instead represent some subjective state of mind. Take the girl in the hijab (Ding Dong Dead’s Destiny Rodriguez) whom he is constantly seeing out of the corner of his eye, and the Russian (frequent extra and bit-player Malina Germanova, whom the sharp-eyed might spot in Octopus 2: River of Fear) who repeatedly pops up when he’s alone to draw him into variations on the same exasperatingly circular conversation. Hijab Girl appears to personify his escalating paranoia, especially his conviction that the neighbors are watching him, judging him, and amusing themselves with his failures, while the Russian fairly explicitly represents his inability to master the life skills that seemingly come so naturally to everybody else, as well as his consequent frustration with the limits of his own intelligence. The former reveals none of her features save two dark and inquisitive eyes, while the latter speaks to him in a foreign language, and is forever deflecting his efforts to unlock whatever secret knowledge she possesses. Both are marked out by their sheer weirdness as pure figments of the man’s imagination. That last part doesn’t seem to apply, however, to the other major symbolic character. The skinny guy with the sandy hair (Matt Turek, from Creep Creepersin’s Creepshow and Erection) figures in the mental lives of both protagonists, and I therefore surmise that he is meant to be a real person whom he and she alike have seen around town. Further hinting in that direction are the wildly divergent loads of psychological baggage with which the two characters have burdened him. For the husband, Sandy Hair embodies the seedy underbelly of the neighborhood. He believes (on who knows what basis) that Sandy Hair lives in a halfway house for drug addicts, and their every interaction plays out like the overture to a mugging. The wife, on the other hand, builds her violent fantasies around the sandy-haired guy, envisioning him as an assassin she’s hired to eliminate her pestiferous spouse.

Now thus far, I’ve been talking up He as if I rather liked it. I could do more of that, too— like I haven’t yet praised the editing and cinematography by frequent Creepersin collaborator Gary Griffith, who is way too good at both of those things to keep toiling in the utter obscurity that has thus far been his lot. So what’s the deal, then, with the paltry star and a half that I’ve bestowed upon He? Simple: this movie is boring. I don’t mean just the untenable attenuation of the premise that marred Creep Creepersin’s Frankenstein, either, although that is part of the problem here. Nor is it merely a matter of He’s somnolent pace, which is actually an asset for a little while. It’s that both those qualities are compounded by the fact that essentially nothing actually happens, and that once you’ve cracked the movie’s code, it becomes altogether too obvious that essentially nothing is happening. So while it aims for Eraserhead, He actually comes much closer to the execrable Jack Harris edit of George Romero’s Season of the Witch. I give this movie a little more credit than that one, simply because Creepersin was working with so much less, but no movie this conceptually interesting has any excuse to be simultaneously this dull.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact