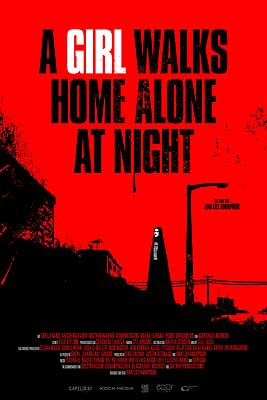

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014) ***½

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014) ***½

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is a strange, slippery film. It’s set in Iran, in a fictional town called Bad Shahre (“Wind City”— although the translingual pun of “Bad City” is plainly deliberate), but was shot in Bakersfield, California. All the dialogue is in subtitled Farsi, as if the movie were a foreign import, but all four of the companies that had a hand in its production are based in the United States. (Indeed, so far as I can tell, Turkey is currently the only Middle Eastern country where A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night has been properly released, although it was screened at the Abu Dhabi Film Festival last October.) Writer-director Ana Lily Amirpour is ethnically Iranian, and a lot of her work explores aspects of Iranian culture that may be opaque to outsiders, but she’s British by birth and has lived in the US since she was a child— making her something of an outsider to that heritage herself. So when Amirpour describes her film as “the first Iranian vampire Western,” it’s difficult to take her entirely seriously, since it isn’t Iranian, isn’t a Western, and can’t meaningfully claim to be the first of anything beyond “feature films made by Ana Lily Amirpour.” A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is, however, one of the few art films with horror subject matter whose creators can make the usual protest that it isn’t a horror movie without sounding infuriatingly insecure and snobbish. It may be about a vampire preying on nobodies in a depressed Iranian city, but it only rarely attempts to scare the audience. Amirpour is more interested in the potential of vampirism as a metaphor for intractable alienation, and her background gives her a perspective on that subject which is well worth considering.

Girls in Iran aren’t really supposed to walk home alone at night. It isn’t as bad as it is in Saudi Arabia, where women aren’t allowed to drive and are forbidden to leave the house unaccompanied by a male relative, nor is it as bad as it was in the early 80’s, when Revolutionary Guardsman roamed the streets of Tehran with whips, administering on-the-spot floggings to women deemed in violation of 7th-century Arabian norms for feminine behavior, but the position of Iranian women is precarious enough that it doesn’t pay to be seen doing anything that smacks too strongly of independence. So in this setting, the title alone, elliptical as it is, tells us that something out of the ordinary is going on.

But before we meet any vampires, we’re introduced to some living people who might seem almost as unexpected as the undead if your impression of life in Iran hasn’t shifted since the height of the Khomeini era. Arash (Arash Marandi) is a twentyish greaser whose prized possession is his 1957 Ford Thunderbird. He knows to the day how long he had to work to save up for the thing. His father, Hossein (Marshall Manesh, from Barb Wire and Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End), is a widower and a heroin addict. I suspect the two conditions are related. And Saeed (Dominic Rains, of Jinn and The Taqwacores) is the heavily tattooed vice trader who keeps Hossein supplied with junk. Hossein owes Saeed a great deal of money that he doesn’t have, and Arash has to part with his beloved car in order to keep the pusher from collecting payment in blood and bone instead.

Arash works for a wealthy family as groundskeeper and handyman. The next day at work, while fixing some furniture in the bedroom of his employers’ spoiled teenage daughter, he succumbs to the temptation to pocket a pair of the girl’s diamond earrings. They should be worth enough to trade Saeed for the T-Bird. But Arash isn’t the only one who has business with the pusher that night. Saeed is observed mistreating one of his whores (Mozhan Marnò) by a strange, silent girl in a traditional black chador (Sheila Ward); we will later learn that this isn’t the first time he’s been spied on thusly, but there’s nothing to indicate that at the moment. Once Saeed is finished slapping Atti around and forcing a blowjob from her in the cramped confines of Arash’s car, Chador Girl lets herself be seen by him, and agrees to follow him home after he initiates direct contact. If it crosses Saeed’s mind that her behavior is curiously at odds with her conservative attire, he certainly doesn’t let on. The rest of the night does not go according to any plan he might have formulated, however. Chador Girl is a vampire, and she kills the dope-pushing pimp with both visible relish and an unmistakable air of moral vindication. Arash arrives to barter the earrings just in time to meet the vampire briefly on her way out the door. Upon discovering Saeed’s body, the boy exhibits no qualms about helping himself not only to his old car keys, but also to the dead man’s valise full of dope and cash.

Some of that heroin is for Hossein, of course, but Arash also knows a career opportunity when he sees one. And Bad Shahre, for its part, seems to like its conspicuously more benign new drug dealer, who suddenly finds his social standing much improved. Walking home stoned as fuck from an ecstasy-fueled costume party that he never would have been invited to previously, Arash encounters Chador Girl. She isn’t hungry, having just fed from a transient, and Arash’s X-induced befuddlement stimulates the same protective instinct that led the vampire to avenge Saeed’s abuse of Atti. She brings the boy back to her basement apartment to sober up in safety, and as the drugs wear off, the two kids find that they quite like each other. At first, Chador Girl resists both her own rising attraction and Arash’s efforts to see more of her. After all, what good ever came of a predator-prey romance? (Note that vampirism in A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night doesn’t appear to be contagious. None of Chador Girl’s victims are ever seen to rise again.) Eventually, though, the allure of a respite to the loneliness of undeath overcomes the vampire’s scruples, and the pair become a couple. But can their relationship survive when Chador Girl feeds on Hossein, taking him for just another low-life whom nobody will miss?

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is a bit like a grown-up (well, mostly grown-up, anyway) take on Let the Right One In. Like that film, this one focuses more on the relationship between the vampire and her human suitor than it does on the former’s monstrous activities, and it uses as the crisis point of the story the moment when the boy discovers what his girlfriend really is. A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night makes a starker departure from conventional vampire fiction, however, in two respects. First, only in a few early scenes— most notably the killing of Saeed and the encounter between Chador Girl and a nosy young boy (Milad Eghbali)— does Ana Lily Amirpour play vampirism for serious horrific effect (and the scene with the little kid pulls back at the last second to end on a joke). Stranger still, there’s no Van Helsing figure in this tale, nor even a proper Jonathan Harker. I realize I’m implicitly blowing the ending by saying this, but nobody in A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night ever so much as suggests that the vampire ought to be destroyed! I’m of two minds about that last point. On the one hand, few subgenres are more in need of a shakeup than vampire stories, and removing vampire-killers from the paradigm is about as big a shakeup as I can imagine. But doing so also tips Amirpour’s hand a little too much with regard to treating vampirism primarily as a metaphor, or alternately opens up A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night to a reactionary interpretation that she simply can’t have intended. That is, in the real world, or in any fictional world that much resembles it, serial murder is generally considered a dick move. But when Arash decides that Chador Girl killing his father isn’t even a dumping offense, let alone cause for torches and pitchforks, Amirpour portrays it as an act of hip rebellion rather than callous depravity. That works only if we posit that when she says “vampire,” what she really means is something like “the modernized, Westernized Iranian youth, disenfranchised, alienated, and demonized by the conservative clerics running the country, and typified for the purposes of this film as misunderstood monsters.” I dislike it when fantastical movies shy away from their fantastical elements like that, and I’m generally of the opinion that a metaphor isn’t good enough if it works only when consciously acknowledged as a metaphor. You see, if we take “vampire” to mean vampire, then A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night turns into a tacit endorsement of the mullahs’ position: without fundamentalist Islam to guide them, the youth of Iran will have their moral faculties wither until they’ll greet even the murder of their parents with, “Nah, that’s okay. Just so long as I’m getting laid…” Like I said, that can’t be what Amirpour was trying to tell us, but it’s a difficult conclusion to avoid in a literal reading of the film.

But leaving aside its somewhat muddled thematic content, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is extremely effective, especially for a debut feature. Amirpour is very much a visual sort of director, and one who recognizes that images can convey elegantly and profoundly ideas that seem clunky and banal when put into words. Everyone at this point is tired of listening to vampires whine about their eternal solitude, but show us one shot of this one riding her skateboard around the deserted streets of Bad Shahre in the dead of night, her chador stretched out behind her on the wind like Count Dracula’s opera cape, and the loneliness comes across at full force. At the same time, though, so does an unexpected countercurrent of playful simplicity. When you’ve got literally all the time in the world and no one with whom to share it, there’s nothing else for it but to cultivate a knack for making your own fun on the spur of the moment. The vampire’s apartment, similarly, is one of the most psychologically evocative settings I’ve seen in ages, telling us things about its owner that no amount of dialogue could communicate without running the movie permanently aground. And I sorely wish we could see more movies shot, like A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, in black and white for aesthetic reasons, out of sheer love for the look that only monochrome can achieve. At the same time, Amirpour also displays an acute appreciation for the mood-setting power of music in film. The Morriconean score by Portland, Oregon’s Federale (presumably the basis for Amirpour’s otherwise baffling identification of A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night as a Western) sounds at once wildly out of place and yet also somehow perfect, while the carefully curated selection of German techno and Iranian expat indie-rock that serves as diegetic music (Chador Girl is a devoted record collector) speaks volumes about the characters’ longing for an officially forbidden but clandestinely available lifestyle. It’s obviously too early to tell yet whether A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is a harbinger of great things to come or merely a fortunate fluke, but it unquestionably establishes Ana Lily Amirpour as a director to watch in the future.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact