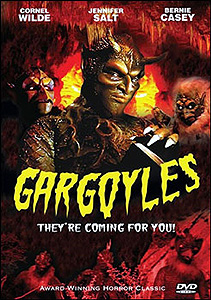

Gargoyles (1972) ***

Gargoyles (1972) ***

I was introduced to the concept of gargoyles when I was seven or eight years old, by a Dimensions for Children playset called “The Forest of Doom.” It consisted of a smallish vinyl terrain map, a snap-together cardstock forest of monstrous trees, and about 40 little plastic figures in roughly 1/36 scale representing the inhabitants of the evil wood and the heroes come to destroy them: knights, wizards, demons, ogres, an impressive winged dragon— and half a dozen gargoyles. The gargoyle figures were easily the coolest things in the set, and in retrospect, a testament to the amount of thought that DFC’s staff artists put into sculpting the molds for such cheap little toys (at least when they weren’t just copying illustrations from the first edition of the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Monster Manual, but that’s not a tangent I feel like pursuing just now). I’ve had a thing for gargoyles ever since, both the Gothic architectural widgets and the style of monster they traditionally represent, so you can imagine my excitement when I learned that there was a horror movie about them. This is the early 1980’s we’re talking about, when the previous decade’s immense corpus of made-for-TV movies still got a substantial amount of airplay, and it wasn’t long before the television schedule granted me a chance to see Gargoyles for myself. I fell head over heels in love with the film, and although I’m naturally more critical of it now than I was when my age was in the upper single digits, I still find that it has held up remarkably well to the passage of time.

The 70’s have been very good to anthropologist Mercer Bolley (Cornel Wilde, from A Thousand and One Nights and The Naked Prey). In any other era, his fascination with comparative demonology could have led, at best, to a curious sideline on a career otherwise spent writing about grain domestication and the geographic dissemination of this or that basket-weaving technique, but the post-hippy popularity of mystical bullshit in every conceivable form has enabled him to become moderately rich and famous by following his true passion. Research for his latest book has brought Bolley into contact with a desert-dwelling eccentric who calls himself Uncle Willie (Woody Chamblis, of The Devil’s Rain). Proprietor of a roadside museum and an amateur collector of Indian lore and artifacts, Willie got in touch with Mercer after seeing him on television discussing a forthcoming project. The old man believes that one of his recent finds would shed revelatory new light on the scientist’s pet subject, but what he wants to show Bolley is so incredible that he refuses to go into any detail up front, for fear of being dismissed as a crackpot. That in itself is nearly enough to make Bolley dismiss him, but he nevertheless agrees to come look at whatever Uncle Willie has before flying off to Mexico for his next dig. Mercer calls in his daughter and research assistant, Diana (Jennifer Salt, from Sisters and Murder a la Mod), and drives out to Uncle Willie’s Desert Museum just as soon as she arrives in New Mexico.

Willie’s mysterious item turns out to be a skeleton. I has to be a Jenny Hanniver, no matter what the old man says to the contrary— never in half a billion years of multicellular life on Earth did nature make a beaked, horned, and winged humanoid! Uncle Willie insists, however, that the skeleton is legit, and Bolley is somewhat discomfited to realize that the bones it’s made up of are all extremely old. Not fossil-old, mind you, but the anthropologist has seen enough skeletal remains in his time to know that it would normally take something like 500 years, give or take a century, to produce that kind of weathering under local conditions. That’s an awful lot of work, finding a whole skeleton’s worth of antique bones, just to make a tawdry tourist attraction. There’s something else, too. Bolley has an eerie feeling that he’s seen creatures like this before. Not in living (or formerly living) form, but in the statuary, carvings, and other artwork of ancient cultures all over the world. That’s exactly what Willie is driving at, actually. The local Indians, for example, believed in a spirit called Nakatakachinko, representations of which bear a distinct resemblance to the thing whose bones he found. What if Nakatakachinko and all the other legendary monsters like it are really garbled references to some unknown species of well-hidden intelligent life, maybe something that comes out only every few hundred years? However crazy it sounds, you can be sure that Uncle Willie himself believes everything he’s been telling Mercer and Diana. You can also be sure that he’s afraid of whatever it is he thinks he’s discovered.

Willie is right to be afraid. Darkness has fallen by the time he’s finished telling the story of his strange skeleton, and night brings something powerful and terrible to his home. Neither of the Bolleys get a good look at the creatures that swarm to attack the Desert Museum, but even a quick glimpse is enough to reveal that these are the old man’s mystery monsters. They clearly intend to remain a mystery, too, for their objective is unmistakably to kill Willie, and to destroy the evidence of their existence that he has gathered. Mercer and Diana escape, bringing the weird skull with them, but Uncle Willie is trapped inside his barn as the inhuman attackers burn it to the ground. The Bolleys make it as far as the nearest little town, where they rent a room at the Cactus Motel and temporarily succeed in fending off the curiosity of Mrs. Parks (Grayson Hall, from House of Dark Shadows and Night of Dark Shadows), the nosy, alcoholic proprietress. Of course, if Mercer is right about what the creatures— which we may as well start calling “gargoyles” at this point— wanted at Uncle Willie’s, then this stay at the Cactus Motel is likely to be only a temporary respite. He and his daughter still have the skull, after all, and it wouldn’t take long for beings intelligent enough to mount that coordinated strike on the museum to figure out that the village up the road was the best place to start looking for it.

The next morning, the Bolleys visit the police station, where they tell the captain (William Stevens, of The Black Godfather and Trouble Man) a judiciously edited version of their story. The captain and one of his patrolman, Jesse (The Strange and Deadly Occurrence’s John Gruber), drive out with them to the scene of the attack, where they find a pack of dirt-bikers riding around the charred ruins. Both cops are extremely stupid men, unable to tell the difference between motocross enthusiasts and Hell’s Angels, so they leap to the conclusion that James Reeger (Scott Glenn, from The Silence of the Lambs and The Shrieking) and his friends must have been the ones who killed Uncle Willie and destroyed his museum. Obviously Mercer and Diana know better, but they can’t realistically tell the captain that. One word about arsonist gargoyles, and the Bolleys would probably end up in jail themselves.

When the gargoyles inevitably come back that night, they’re only partially successful. That is to say, they get the skull out of the Bolleys’ motel room, but one of them is struck and killed by a passing truck during the getaway. Now Mercer has a fresh carcass to study, and Diana thinks she has a way to get Reeger and the others released. Neither undertaking goes well. The captain is out when Diana goes to see him, and Jesse thinks she’s full of shit. They argue for a bit, but Diana eventually admits defeat and walks back to the motel. Meanwhile, the gargoyles sortie in force to recover their fallen fighter, led in person by the chief of their tribe (Bernie Casey, from Cleopatra Jones and The Man Who Fell to Earth, with the overdubbed and electronically distorted voice of Vic Perrin). They trash the motel and Mercer’s car, beat the shit out of Bolley himself, and even kidnap Diana, who returns from her futile errand of mercy at the very most inopportune time. The one upside is that the night’s havoc forces that pig-headed police captain to listen to reason. The next day, he rather abashedly deputizes Reeger and the other dirt-bikers to form a search party to help him and Bolley find the gargoyles’ lair and rescue Diana.

I highly recommend Gargoyles to any fan of Clive Barker. It’s handled somewhat clumsily and inconclusively here, but Gargoyles is one of the earliest films I can think of to employ Barker’s oft-used theme of monsters who just want to be left alone falling into conflict with humans bent on their destruction. Note that I’m talking about something more than just a sympathetic treatment of the monsters, which cinema has been doing sporadically since at least Frankenstein. What we see in Gargoyles (and in Nightbreed, Transmutations, “The Skins of the Fathers,” etc.) is a society of monsters, and the fulcrum of the movie’s plot is the fraught relationship between that society and ours. The gargoyles, at least if we disregard the crudely alarmist voiceover prologue that was added for the overseas theatrical release (which is irritatingly preserved in currently available home video editions), are not evil per se. They, like us, are just intelligent apex predators who feel no compunctions about putting the needs of their species ahead of those of any other. The gargoyles are physically powerful and endowed by nature with considerably better weaponry than we got, but they’re very few in number, and their life cycle makes them exceedingly vulnerable to any enemy clever enough to discover their lairs. We, meanwhile, are the Earth’s dominant megafauna, and we’re not interested in surrendering or indeed even sharing the title. Plus, we have technology on our side, while the gargoyles don’t seem to use even basic tools. The advantage in any serious clash between the two species lies plainly with humanity, and it is therefore rational for the gargoyles to kill any human who learns of their existence. Of course, it’s just as rational for humans to want to kill gargoyles, but the grotesquely lopsided balance of power tends to make us look like the real monsters as soon as a critical mass of information about the gargoyles and their society comes to light. Crucially, the makers of Gargoyles obviously understood how their portrayal of the creatures was going to play— just look at how the Bolleys’ interaction with the gargoyles changes over the course of the film. Mercer and Diana are the best-informed characters on the subject of the things living in that cave out in the desert, not least because they’re the only ones who ever speak directly to the gargoyle chief. The Bolleys are also the ones who bear the brunt of the gargoyles’ violence once Uncle Willie is no more. It’s obviously significant, then, that they of all people pull back in the end from eradicating the creatures, permitting a single breeding pair to escape after the nest is destroyed. Mercer and Diana are meant to be our surrogates among the cast, and the story is designed so that our perceptions of the gargoyles evolve along with theirs. The recognition that the monsters are the underdogs here is a major factor setting Gargoyles apart from the run of the creature feature mill.

Another one is Stan Winston’s gargoyle makeup. This was Winston’s first gig as a monster-maker, and the conditions he was working under were fairly limiting. Nevertheless, the genius that would later breathe life into latex for Aliens, Predator, and Galaxy Quest is immediately obvious. It’s difficult to believe, looking at Winston’s work, that Gargoyles was made for TV; indeed, I’m having a hard time thinking of any early-70’s movies made for theatrical release in which the creature costumes were any better. Their one consistent weakness is that they tend to bunch up around the joints, revealing their origins as off-the-shelf wetsuits. (The breeder-caste costumes suffer a second defect, in that their wings are just nowhere near big enough to be believably functional.) The smartest thing Winston did was to make at least a dozen distinct masks. All of the adult gargoyles save the chief were played by the same three stuntmen who portrayed the background members of Reeger’s dirt bike gang, and so there are never more than four of the creatures onscreen at any one time. That isn’t immediately apparent, though, because the viewer quickly comes to recognize individual gargoyles, of which there are several times as many. Not all of the masks are up to the same standard of imagination or craftsmanship, but even the worst is much better than I would normally expect from special effects makeup in a television production— and the best are eerily lifelike. In a way, it’s almost depressing. 30 years ago, this is what made-for-TV monster movies looked like; today, we get crap like Mammoth and Hydra.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact