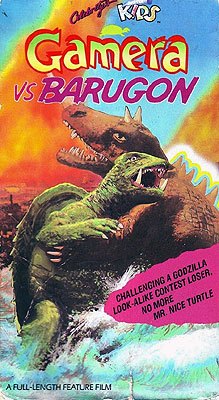

Gamera vs. Barugon / War of the Monsters / Daikaiju Ketto: Gamera tai Barugon (1966/1967) ***

Gamera vs. Barugon / War of the Monsters / Daikaiju Ketto: Gamera tai Barugon (1966/1967) ***

We have here something utterly unexpected-- a genuinely good Gamera movie. To be sure, Gamera vs. Barugon/War of the Monsters/Daikaiju Ketto: Gamera tai Barugon has its problems, especially in the pacing department, and the story becomes increasingly hard to swallow as it progresses, but most of the things that usually get in the way of unironic appreciation are absent here. To begin with, the dubbing is actually pretty decent by kaiju eiga standards, and is light-years ahead of what we can usually expect from distributor Sandy Frank. Also in the movieís favor is a startlingly unformulaic plot with as many twists and reverses as a Clive Barker fantasy novel. Best of all, thereís no annoying little kid! Not a one! All I can think of by way of explanation for this merciful oversight is the fact that, alone in the series, Gamera vs. Barugon was directed by Shigeo Tanaka, rather than series regular Noriaki Yuasa. Even so, it remains puzzling because the screenplay was written by Nisan Takahashi, just like those of all the other Gamera films.

Gamera vs. Barugon essentially picks up right where Gamera left off. After a quick recycled-footage recap of the previous film (in which said recycled footage is tinted blue so as to minimize its clashing with the rest of the movie, which is in full color), a voice-over explains that the huge rocket in which Gamera was launched into space collided with a radioactive asteroid (ever notice that, in these movies, asteroids and meteorites are always radioactive?) on its way to Mars. The resulting destruction of the rocket freed Gamera, and the monster wasted no time in returning to Earth to wreak havoc. In particular, Gamera seeks out a hydroelectric dam, which he destroys in order to feed on its accumulated energy. And then, without warning, the movie forgets all about Gamera, and introduces us to a group of semi-nefarious characters with what seems to be a fool-proof get-rich-quick scheme.

If the group can be said to have a leader, it is World War II veteran Hirata (Akira Natsuki). Twenty years ago, when he was stationed on New Guinea, Hirata stumbled upon a flawless opal, twice the size of a manís fist, in a jungle cave. He had just enough time to hide the gem under a pile of rubble before he and his garrison were evacuated. Now, he has assembled his brother, Keisuke (Kojiro Hongo, of The Bride from Hell and The Return of Daimajin), and two of his long-time friends to tell them about the stone. He needs the three of them to retrieve the opal for him because he is now a cripple, and is incapable of making the trek through the jungle that the task requires. Hirata proposes to split the proceeds from the sale of the gem equally with his three comrades if they will help him carry out his plan. He wants them to pose as sailors on a New Guinea-bound freighter, to sneak away from the ship upon landing, and then to sneak back in time to make the return trip to Japan. If anyone asks where they went while the ship was in port, they are to offer the cover story that they went into the jungle to recover the bones of a wartime friend who was lost before the evacuation. They will be furnished with a briefcase full of pig bones to back their story up.

Now, time out for a moment. Have you ever seen anyone from New Guinea? Chances are, youíd say such a person was black. And it probably comes as no surprise that Japan is not exactly waist-deep in black actors... I suppose what Iím getting at is this: Have you ever seen a Japanese person in blackface? Well then, watch Gamera vs. Barugon, and that particular gap in the tapestry of your experiences will be filled. When Hirataís accomplices land on New Guinea (oddly enough in a helicopter, rather than the ship that we had seen them on earlier), they find themselves in a stone-age village inhabited by large numbers of conspicuously Japanese extras in blackface applied with varying degrees of care. While the adventurers try to get their bearings and figure out exactly where in the jungle their cave is, they discover that one of the natives is the adopted daughter of a Japanese anthropologist. This girl, Karin by name (Kyoko Enami, who is not wearing blackface, incidentally), warns them that they must stay out of the jungle, and by no means go anywhere near any caves. The location of the caves, she says, is known as Rainbow Valley, and it is inhabited by an evil spirit. We, of course, know what this means, but Keisuke and company are not interested, and insist on forging ahead into the jungle in search of the cave where Hirata hid the opal.

But surprisingly enough, nobody gets eaten by a monster out in the jungle. Rather, everybodyís problems can be traced to Omotura (Koji Fujiyama, from Zatoichi Challenged and Female Prisoner Scorpion: Beast Stable), the member of the team who procured the fake passports. After the third member of the party finds the opal (and it is a damned impressive one, even if it is obviously made of plastic), Omotura conveniently neglects to mention the huge poisonous scorpion crawling up the manís leg, allowing it to fatally sting him. Then, after he talks his other partner into giving him the opal, he arranges for a cave-in to trap Keisuke inside. Finally, he returns to the freighter for the trip home, plotting, or so we imagine, a way to out-maneuver Hirata once he reaches Japan.

Meanwhile, it seems that Omoturaís cave-in was rather less effective than he had imagined, because we next see Keisuke awakening in a bed back in Karinís village. When Keisuke explains to Karin what happened, the girl panics, and rushes out to talk to her adopted father about what she has learned. That opal, apparently, is no opal, and it is of the most pressing importance that it be returned to its cave immediately. After quite a lot of hysterics, Karin convinces the anthropologist that the only answer is for her to go to Japan with Keisuke to recover the gem.

But Karin is already too late. You see, Omotura got himself a nice case of athleteís foot out in the jungle, and he has spent much of the trip home in the infirmary, holding his feet under an infrared lamp. Eventually, a member of the crew convinces him to come out of sick-bay, and join the other men in a game of mahjong. Of course, Omotura has also spent much of the trip fondling the opal, and he had been doing just that when the man walked in. Omotura swiftly hides the opal in his sheets, and goes off to play, but he predictably leaves the infrared lamp lit, and he equally predictably leaves it pointed at the part of the sheet that conceals the gem. If you donít know whatís coming, you are clearly a rank newcomer to this business. Everybody together, now: ďThe infrared rays heat the opal, causing it to split open and reveal a small, lizard-like creature covered in purple-blue slime.Ē And now, the second verse: ďThe infrared rays then cause the creature to grow at an alarming rate, until it is large enough to destroy the ship from within.Ē Very good, very good...

So, we have returned at last to the reason we watch these movies-- the city-smashing monsters. This Barugon beast is arguably the least outlandish of the monsters in the Gamera mythos; were it not for his super-powers, heíd actually be sort of mundane. Heís a reptile, a quadruped, with a long horn on the end of his nose and a staggered double row of luminescent spines on his back. And as we learn shortly after he comes ashore, he has a long, chameleon-like tongue with which he blows frost all over everything he doesnít like. After a brief period of smashing and freezing things, Barugon comes face to face with Gamera, whom the filmmakers seem finally to have remembered was supposed to be in this movie. Now, you may recall from the first film that Gamera is a creature of heat and fire. So what do you think might be the outcome when he comes up against a monster whose main attack involves extreme cold? Goddamned right. Gamera gets his ass kicked from one end of the city to the other, finally ending up as a big-ass turtle-shaped iceberg. The victorious Barugon then resumes his rampage.

What we have stumbled onto is the reason for Gamera vs. Barugonís effectiveness-- its willingness to take chances with the monster movie formula to which the original Gamera so slavishly and pointlessly adhered. This is actually Barugonís movie; Gamera wonít thaw out again until the last fifteen minutes or so. In the meantime, an astounding array of seemingly sure-fire gimmicks will be deployed to defeat the former monster, both technological and mystical in nature. The first, and most obviously doomed, attempt comes when the military tries to get around Barugonís Tongue of Frost attack by bombarding him with surface-to-surface missiles from a range of several miles. I have no idea how, but the monster sees the attack coming and responds by unleashing the weapon responsible for the name of his old stomping ground on New Guinea-- Rainbow Valley. Those spines running down Barugonís vertebral column begin glowing even more brightly than usual, and a literal rainbow arcs from the monsterís back to sweep across the assembled missile launchers, destroying everything it touches. From this point on, all bets are off. This is what I was talking about when I said that Gamera vs. Barugon reminds me of a Clive Barker novel; like that English writerís works (especially Imajica and The Great and Secret Show), this movie repeatedly works up to what seems sure to be the conclusion, only to surprise the audience with the failure of one endgame strategy after another.

The last thing I want to address regarding Gamera vs. Barugon is the character of Gamera himself. This is actually perhaps the weakest point in the movie. The purpose of this film, at least in part, seems to be to shift Gamera from the role of indestructible menace to invincible defender of Earth (ďGuardian of the Universe,Ē as the title of a belated 1990ís sequel puts it). The problem is that nothing remotely approaching an explanation is offered for the change. Gameraís first battle with Barugon is handled very much like the struggle between Godzilla and Angiras in Gigantis the Fire Monster/Godzilla Raids Again-- a Darwinian contest for territory and resources rather than a showdown between good and evil. But the climactic duel of Gamera vs. Barugon casts Gamera very much in the role of the hero; despite the fact that Gamera began the film wrecking hydroelectric dams and flooding cities, the movieís human characters seem to see no need to feel threatened by him after he finally finishes off Barugon. Compare this to the way the early Godzilla movies handled the presence of two battling monsters: the palpable sense of relief with which the characters in King Kong vs. Godzilla observe that the victorious Kong is swimming back home, rather than returning to Japan; the all-out attack on Godzilla that follows the death of Angiras in Gigantis the Fire Monster. For that matter, look at the new heisei Godzilla movies, like Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah. Even after Ghidorah is destroyed, the continued presence of the rampaging Godzilla puts a damper on any mood of celebration that might have developed. Nothing like that happens in this movie, though. Itís all smiles and cheers and chirping birds when Gamera flies off into what certainly ought to have been the sunset after slaying Barugon.

That said, I stand by my contention that Gamera vs. Barugon is, on the whole, a good movie. Itís pretty slow-moving at first, and it demands formidable powers of suspension of disbelief, but it succeeds through its willingness to defy audience expectations and its unexpectedly solid sense of character motivation (and for that matter, its success in remembering the existence of its characters at all, once the fighting begins). The absence of irritating children and the fact that the monster battles are far better handled in this film than they would be in later installments are also major points in its favor.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact