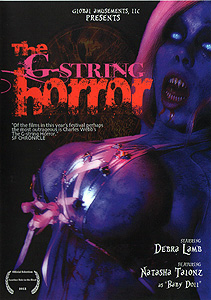

The G-String Horror (2012) **

The G-String Horror (2012) **

It’s hard to come up with really new subject matter for movies, but people get bored watching the same old stories retold with new faces just the same. It’s even more difficult in a formulaic genre like horror, where audiences come in with certain non-negotiable expectations, but nevertheless demand to be surprised from time to time. Consequently, it makes some sense that one of the big trends in 21st-century horror cinema is formal experimentation, with filmmakers trying to make end-runs around the freshness-vs.-formula dilemma by tinkering with the most basic assumptions of narrative technique. Most famously, there’s the “found footage” gimmick, in which a movie is passed off as having been shot by characters within it. We’ve seen a fair bit of that in the fourteen years since The Blair Witch Project, but many of that style’s fundamental problems still remain to be adequately solved. That being so, I find it rather curious that we don’t see more of the other major strain of formal radicalism in circulation these days, the fake documentary. Pseudo-documentaries make in some ways an even sharper break from the narrative norms of cinema, while simultaneously offering more flexibility of approach and providing a built-in answer to the “why are they filming this?” question that continues to bedevil the found footage subgenre. Still, as The G-String Horror shows to its own disadvantage, the fake documentary requires just as unwavering a commitment to its premise as the other faux-verite style. The makers of such movies can’t afford to let their poker faces slip any more than the supposed footage-finders, lest the film be undone by its own artifice.

San Francisco’s Market Street Cinema wasn’t called that when it opened on December 22nd, 1912. Back then, it was Grauman’s Imperial Theatre, part of the same prestigious chain as the famous Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Los Angeles. The grand old cinema changed hands a number of times after its first sale in 1919, variously belonging to the United Artists, Premiere, and Lowes chains before passing into independent hands (and acquiring its current name) in 1972. In the old days, Market Street’s entertainment district was where all the city’s studio-affiliated theaters were located; it was where you went if you wanted to see the biggest films with the biggest stars on the biggest screens, weeks before they migrated to the smaller, independently owned neighborhood theaters. By the 70’s, though, Market had gone decidedly down-market. The studio chains had been broken up by the Federal Trade Commission, the suburban multiplex was the wave of the future, and the old movie palaces were obsolete relics of an extinct business model. Plus, the whole area was turning skanky— so much so that the people who took over the Imperial in ‘72 turned it into a giant porno house! Of course, that trade’s days were numbered, too, with home video waiting in the wings to strangle theatrically released porn in the 80’s. When that happened, the Market Street Cinema was reborn yet again as a strip club and de facto whorehouse. It’s that latest incarnation that concerns us now, for it is the setting of The G-String Horror.

It’s an interesting conceit this movie has. Like a lot of very old buildings (or at any rate, what passes for very old in the United States), the Market Street Cinema has a real-life reputation for hauntedness— enough so that one of those bullshit ghost-hunting shows devoted an episode to it a year or two ago. The G-String Horror has it that writer/director Charles Webb (playing himself) was inspired by the rumors to use the place as the primary shooting location for a direct-to-video horror movie, but encountered so much creepy weirdness on the premises that he shifted gears to make a documentary on the haunting instead. With the cooperation and assistance of the club’s business manager, Big Mike Gleason (also playing himself), Webb interviews the staff about the strange things they’ve seen and heard on the job, seeks out former employees to do the same with them, collects pertinent lore on the building’s past, and sets out to capture some of the more predictably recurring manifestations on video.

It turns out there are at least five supernatural tenants dwelling in the converted theater. The oldest of them is a grotesquely deformed Gypsy woman who seems somehow to personify the building itself. She hates what the Imperial (she still insists on calling it the Imperial) has become, and resents not just the current owners and their employees, but also the other four spooks, all of whom took up residence during the cinema’s lawless new career as a strip club. Among that lot, the ickiest but least dangerous is the ghost of a fetus one of the dancers once miscarried in the women’s bathroom. It mostly just cries like the baby it never got to be, but still— phantom miscarriage? Ew! Slightly more troublesome are Red and the Janitor, who were killed in a fire backstage. Both of them are nasty to look at and fairly aggressive about manifesting visibly, plus Red enjoys shoving people on the stairs. Even so, there’s never been a report of either one seriously harming anybody. No, the ghost you have to worry about at the Market Street Cinema is Baby Doll. Like Red, she was a stripper who died on the premises, but Baby Doll’s demise was no tragic accident. One night in 1992, she was entertaining an after-hours birthday party, and the customers turned out to be a bunch of psychos. They murdered her in the basement lap-dance area, burned her body, and hid the ashes in a convenient vase. So far as we can tell from The G-String Horror, the crime was never formally discovered, although Baby Doll’s fellow dancers were quick enough to grasp the approximate significance of her disappearance. Understandably, the murdered girl now harbors a fierce grudge against guys who frequent titty bars, but she’s also developed a rather less explicable tendency to view strippers who aren’t dead yet as rivals. Face-to-face meetings with Baby Doll never go well for anybody.

It’s therefore rather unfortunate that the activities of Webb and his film crew have had the effect of getting the ghosts all riled up, and Baby Doll especially so. Manifestations proliferate and become increasingly threatening, until Big Mike’s boss is just about ready to toss Webb out on his ass. The haunting spreads to the film itself, with unpredictable and irreproducible anomalies appearing on the videotape whenever Webb watches the dailies from his latest shoot. Most ominously of all, Natasha Talonz (of Vaginal Holocaust and Black Devil Doll), Genna Darling, and Ed Bowers— the actors Webb hired to play Baby Doll, Red, and the Janitor in scenes dramatizing the stories associated with them— seem genuinely to be channeling the wills and personalities of their spectral counterparts. Eventually, Webb turns to psychic Lady Zee (Debra Lamb, a dancer and fire-eater who performed in those capacities in Satan’s Princess and Body Parts) and her nephew, Sean (Trevor O’Donnell), for paranormal assistance. Lady Zee knew something like this was coming. She received a visitation from the old Gypsy a little while ago, and although the spirit of the theater was as unhelpfully vague as such beings always seem to be on the details, the transdimensional briefing did convey some sense of the danger Zee would soon be asked to face. Forewarned or not, though, Lady Zee has utterly failed to appreciate just how powerful Baby Doll has become.

Honestly, I was overstating the case just a little at the beginning of the review, when I drew the distinction between found footage movies and faux documentaries. There’s no reason a single movie can’t play it both ways at once, and The G-String Horror does that to a minor extent. It begins with what purports to be a VHS tape discovered during filming in the basement of the Market Street Cinema, which depicts Baby Doll’s murder. Presumably it was left behind by the perpetrators, even though that makes absolutely no sense on any level. The absurdity of the killers videotaping their crime and then leaving the evidence at the scene isn’t the real problem with the prologue, though. Rather, the real problem is that Baby Doll is played in it by Natasha Talonz, just as she is throughout the film. It’s a subtle mistake, but very nearly a fatal one. Remember the premise we’re working within here; for the purposes of the story, Natasha Talonz and Baby Doll are two separate people, and the difference between them theoretically grows in importance over the course of the film, as the ghost increasingly asserts herself over the actress. By having Talonz play both herself and Baby Doll, Webb not only blows the illusion that The G-String Horror is a documentary, but also renders a key plot point virtually invisible. The same presumably applies to Genna Darling and Ed Bowers, although it’s less important in their cases whether we’re supposed to be watching a legitimate ghostly manifestation or a dramatization of same in any given scene. This is what I meant before about maintaining the poker face. In a fake documentary, the movie itself is an actor. It can no more be allowed to break character than any of the human performers, and its “costume”— which is to say, all the things that permit fiction to masquerade as nonfiction— must be both complete and character-appropriate. To carry the analogy one step further, Talonz’s dual casting is a lapse equivalent to the aliens’ tennis shoes in Attack of the the Eye Creatures.

That’s really unfortunate, because until the issue of the actors getting possessed arises, The G-String Horror is often surprisingly effective. It doesn’t matter that barely anyone among the cast has any meaningful acting experience, because most of these people are just playing themselves anyway. The location is terrific, even without giving real-world credit to any of the stories we hear told about it. The film is convincingly structured as a documentary, and so long as the ghosts are presented mainly via anecdotes related by various members of the Market Street Cinema staff, it’s easy to go along with the idea of Webb and his colleagues getting more than they bargained for from what sounded at first like a can’t-miss marketing gimmick. And the “fictional nonfiction” format is simply one that I very much enjoy, and have enjoyed ever since I read Steven Caldwell’s Aliens in Space: An Illustrated Guide to the Inhabited Galaxy as a child. Movies like this one (or books like Caldwell’s) are a sort of game, in which the creators must tell a story without looking like they’re doing so. If it goes wrong, the result can be irritatingly precious, but the inherent challenge can also push people to make something far more interesting than their talents and resources could yield in a more conventional treatment of the same material. The G-String Horror falls into the latter category, even though it doesn’t really work the way it was supposed to.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact