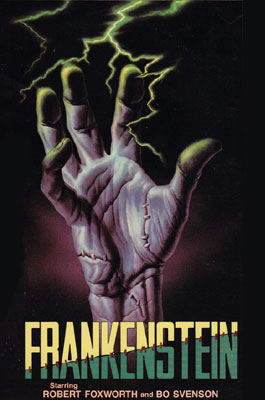

Frankenstein (1973) ***

Frankenstein (1973) ***

1973 saw the broadcast of two competing two-part TV movies adapted, with varying degrees of fidelity, from Mary Shelleyís seminal sci-fi horror novel, Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus. I emphasize their roots in the book, because in each case thatís what made these teleflicks so different from the myriad theatrically-released Frankenstein movies to appear since 1931. The made-for-TV Frankensteins of í73 were alike in foregrounding not the hubris of Victor Frankensteinís attempt to usurp the divine power of creation, but rather his callous irresponsibility in turning his creature loose to fend for itself against an implacably hostile world when it failed to satisfy his expectations. Otherwise, though, they could scarcely have been more different. Oneó Frankenstein: The True Storyó was a lavish undertaking, shot on 35mm film in the UK, where the ongoing implosion of the native cinema industry meant that top-shelf talent could be hired for pennies on the dollar, and wove together in extremely innovative ways visual, narrative, and thematic elements drawn from virtually every previous interpretation of the story. Indeed, it was such an impressive production that a somewhat condensed cut was released to theaters in a variety of markets abroad. The other, produced and co-written by Dan Curtis, 1970ís American televisionís foremost master of the macabre, would never have survived on the big screen. Curtis used videotape instead of film, and his cast and crew never set foot off of the MGM back lot during the entire shoot. While the rival Frankenstein included among its cast James Mason, Agnes Moorehead, David McCalllum, Tom Baker, John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson, and Jane Seymour, the biggest name Curtis could offer was Bo Svenson. And indeed the highlight of his Frankensteinís post-broadcast afterlife was a VHS release hosted by Elvira, Mistress of the Dark, as part of a series that also included The Human Duplicators and The Blood Waters of Dr. Z. So obviously this one must suck, right? Wrong! Although itís by no means equal to Frankenstein: The True Story, the Curtis Frankenstein is genuinely competitive with it for much of its length, until a rushed and underwritten final act spoils things a bit. Also, in broad strokes at least, this version enjoys the distinction of being the nearest thing to a faithful adaptation that had yet been attempted for screens of any size at the time of its premiere in January of 1973.

In 1856, at the University of Ingolstadt in Bavaria, Professor Waldman (William Hansen, from Willard and The Terminal Man) has invited a young doctor by the name of Victor Frankenstein (Robert Foxworth, of The Devilís Daughter and Prophecy) to present what he considers to be a very exciting paper before the college of medicine. We donít get to hear much of it over the outraged jeering of the audience, but Frankensteinís central point seems to be that as the accelerating pace of social and technological advancement threatens to leave mankind adrift in a world to which it is no longer adapted, it will be incumbent upon scientists to develop new strains of humanity better suited to emergent conditions. The reason for the sharp divergence between Waldmanís reaction and the othersí is simple; the old professor assumes that Frankenstein is speaking merely theoretically, while his younger colleagues correctly deduce that the maverick doctor means every word he says, on a literal, practical level. In fact, with the help of his assistants, Otto (John Karlen, whom Curtis also used in Night of Dark Shadows and The Picture of Dorian Gray) and Hugo (George Morgan), heís already built the prototype of his Mk II Man (Svenson, from Snowbeast and Curse II: The Bite), although he has yet to outfit the creature with a heart commensurate with its huge stature and superhuman strength and vitality.

That hostile crowd at the university has Frankenstein more eager than ever to finish the project, giving life to his creation and thereby (or so he imagines) silencing his narrow-minded, short-sighted critics. Fortuitously, the weather forecast calls for a thunderstorm tomorrow night, of exactly the sort needed to power the animating equipment that fills most of his attic laboratoryó but obviously that means Victor, Otto, and Hugo will have to hustle to get the creatureís heart installed. With that in mind, the experimenters make a shopping excursion to the local graveyard as soon as the rest of Ingolstadt has gone to bed, but their luck runs out at the last moment. In their hurry to dig up a fresh body with a stout heart, Frankenstein and his companions awaken the cemetery caretaker, and Hugo is fatally shot while running away. He lasts just long enough to be carried back to Frankensteinís lab, and to bequeath his own heart (which, obviously, he wonít be needing anymore) to the synthetic man. The prospect gives Victor and Otto the willies at first, but they soon convince themselves that accepting their friendís donation is both the best way to honor him and the only way to give his premature death meaning.

Before any such work can begin, however, Frankenstein has a bit of a brushfire to put out. Among the letters that have been piling up unread while he and his assistants worked like fiends on their Man of the Future was one from his fiancťe, Elizabeth Clerval (Susan Strasberg, of Mazes and Monsters and Sweet Sixteen), announcing that she was coming up from Geneva to visit. And because women in the 19th century never went anywhere without an entourage of males to stand guard over their vaginas, sheíll be accompanied by Henry Clerval (Dear Dead Delilahís Robert Gentry), her brother and Frankensteinís best friend, along with Victorís father, Alphonse (Philip Boureuf, from Chamber of Horrors and The Last Child), and little brother, William (Bibleman himself, Willie Aames, whom we may see again if I ever get around to Bottle Monster or Cut and Run). The coach carrying the lot of them pulls up to Frankensteinís doorstep just as he and Otto are running the final systems checks on their animation engine, and Victor makes an extremely poor showing for himself while trying to convince his family and friends that now is not a good time for them to drop in. He can look forward to plenty more of the same in the coming months, too, because Alphonse has taken out a lease on a villa in Ingolstadt. Indeed, Alphonse and Elizabeth have decided that it would be a great idea for her and Victor to be married right there in town, rather than continuing to wait for a break in his responsibilities at the university. Frankenstein just barely manages to avoid a fight with every single one of his loved ones while simultaneously preventing them from barging upstairs to see his laboratory.

At first it seems as though that nightís life-giving operation is a failure. Frankensteinís equipment channels lighting strike after lightning strike into the synthetic manís body, but each time the galvanic reaction fizzles out before activating the heart. As the storm recedes, Frankenstein dejectedly looks around his lab, and for the first time sees what those hecklers at the college of medicine saw when he outlined the aims of his research. He recognizes all of a sudden that he has on his hands two dead bodiesó one of them assembled from pieces of who knows how many moreó a fortune in electrical apparatus that he canít even explain without confessing to crimes ranging from grave robbing to necromancy, and a detailed record of all those crimes in his notes, plans, and documentation of the experiment. All that shit has to go, now that the project has come up bust, and it has to go now! But while Victor and Otto are gathering up all their papers for the fire, the lightning rod on the roof captures one final bolt, and at last the man-made man begins to stir.

Again Frankenstein reverses courseó or mostly, anyway. Although the experiment is obviously a success in crude terms, Victor and Ottoís post-jumpstart examination of their handiwork quickly reveals that the creature hasnít turned out quite the way they imagined. First of all, even though its brain came from a deceased colleague of Frankensteinís, Victor finds no sign of recognition when he looks into its eyes. Furthermore, despite considerable effort expended to ensure that the Mk II Man would be as superior mentally as he is physically, Frankenstein at first can see little indication that his creature has any mind at all. And because these are 19th-century scientists weíre dealing with, Victor and his assistants had put great stock, during the planning phases, in the beauty of their creation. But even if we disregard the dense tracery of livid suture scars covering its face and body, the cruel fact is that the thing would still look like Bo Svenson without them. Rather disappointing all around, then. Still, matters soon begin looking up a little. The speed with which the creature learns to walk, to coordinate its hands and eyes, and to grasp at least the concept of verbal communication suggests that it is highly intelligent after all; it just doesnít know anything as yet. Now that Frankenstein understands that heíll have to treat the synthetic man as an immense infant, he sees that the situation may indeed be salvageable, albeit at the cost of a great deal more work than heíd anticipated. Rather inconveniently, however, heíll have to leave the first round of the creatureís conditioning to Otto, because heís got a date with Elizabeth right nowó and given the hard feelings engendered by her last visit, he canít afford to blow this one off altogether. Victor tells Otto that heíll return as soon as he can, and then heads off to his fatherís villa.

Otto makes a fateful decision while Frankenstein is out: he teaches the creature to play catch. Iím sure that doesnít sound fateful, but a lot of bad things can happen when you combine the mentality of a two-year-old with the strength of a grizzly bear. Having learned the game and found it fun, the creature doesnít want to stop, and when Otto tries to take the ball away from it, it struggles to keep its toy, just like any small child would. Being neither small nor a child, however, its struggles prove considerably too much for Otto, and Frankenstein returns to find a second dead assistant and a confused, unhappy monster-man. Now itís Frankensteinís turn to do something fateful. Although his first impulse is to put a bullet through the artificial beingís brain, he is ultimately unable to pull the trigger. After all, Ottoís death canít really be considered the creatureís fault, for all that its giant hands were the ones that broke his neck. Frankensteinís monster will have to be taught, thatís all. And until it can be taught, it will have to be restrained. Frankenstein straps the creature back down to the workbench on which it was assembled, and then sneaks over to Ottoís house with the dead manís body in order to fake up a plausible-looking fatal accident. Of course you realize where this is going. The creature quickly grows bored alone and motionless, and neither the leather straps on the table nor the locked door to the laboratory are any impediment to its titanic strength. When Victor comes home this time, his creation is gone without a trace.

Frankenstein basically splits in two at this point. On one side, we have Victorís efforts to patch things up with his family while simultaneously holding them at armís length so that he can look for the fugitive creature without confessing to what heís done. The requirements of those projects being obviously in opposition, he manages only to make Alphonse fear for his sanity, to convince Henry and William that heís turned into an asshole, and to lead Elizabeth to suspect him of having a lover on the side. The creature, meanwhile, blunders about the Bavarian countryside, learning one painful lesson after another about cold, thirst, hunger, loneliness, and most especially the widespread human prejudice against anyone visibly different. The latter lessons become the primary means whereby Frankenstein belatedly keeps track of the synthetic manís movements, because more often than not they result in shattered bones and mangled corpses. Again, though, the creature doesnít mean to maim and kill so profligately. Itís just that humans are so damned breakable, and yet so irrepressibly eager to invite being broken.

Eventually, though, the creature finds something resembling a home in the woodshed of a modestly prosperous peasant family called Delacey. There are four people living in the cottage adjoining the shed: old Charles, the patriarch (Jon Lormer, from Creepshow and Dimension 5); his lovely, blind daughter, Agatha (Heidi Vaughn); his boisterous, seafaring son, Felix (Brian Avery, of Bigfoot: The Unforgettable Encounter and The Curse of el Charro); and Felixís fiancťe, Safie (Malia Saint Duval), a Spanish girl whom he picked up on his last voyage. The creature avidly listens through the thin wall dividing its shed from the dining room where Agatha teaches Safie the language and customs of her new country, and becomes nearly as adept in them as the bride-to-be herself. It also observes how Agathaís blindness sets her ineffably apart from even her most intimate companions, and conceives the notion that here at last is someone who might be able and willing to understand it. Maybe she would have, too, if Felix had let her. But when he, Charles, and Safie come home from some outing to find a gigantic, horribly disfigured stranger in the house, looming over the defenseless Agatha, Felix never considers for a moment whether or not she needs defending. Again the creature is forced to fight, and again Frankenstein gets called in to heal those who fucked around and found out. This time, though, Victor learns enough from his patient to track the monster to its latest lair, setting the stage for a reunion that will finally answer some of the questions that have been tormenting the synthetic man ever since it struck out on its own. And once the creature grasps that it has met its creator, it gets a new idea about how to make its outcast existence bearable. Frankenstein will make it a mate. And lest there be any ambiguity in the creatureís meaning, that isnít a proposal. Itís a command, and Frankenstein isnít going to like what happens if he disobeys.

Thereís no denying that Frankenstein is cheap and stagy, or that the videotape cinematography fights against all of director Glen Jordanís efforts to give the picture a strong esthetic personality. Furthermore, the staginess extends beyond the look of the film to encompass several of the key performances. Robert Foxworth in particular had me thinking far too often of a recording I once saw of a Broadway musical version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde starring David Hasselhoff (no, really!) in the title roles. Right through the end of the creation scene, Frankenstein looks like itís going to be rough going indeed. But then an astounding thing happens. Bo Svenson, of all people, not only stabilizes the rapidly listing film, but seems to inspire all his fellow performers to match his efforts with their own. Out of nowhere, the whole cast appears to recalibrate themselves, as if belatedly recognizing that theyíre all a production of this kind really hasó the only basis on which it can sell whatever intrinsic virtues the writing might have provided.

The extraordinary thing about Svensonís take on the creature is that it remains fundamentally childlike in its affect throughout. Even in the final phase of the story, as the creature prosecutes its campaign of vengeance against Frankenstein for going back on his promise to build it a mate, Svenson plays it like a small boy giving tit for tat to another kid mistreating him on the playground. That approach wins unshakable audience sympathy by hearkening back to the primitive, coarse-grained conception of fairness that we all remember having in our earliest youth. But at the same time, itís chilling, because we also remember the utterly inflexible notion of punitive justice, unleavened by mercy or empathy, that goes along with that conception. Who would ever want to go up against a righteously aggrieved kindergartener with this kind of raw physical power at his command?

Before we get to the creatureís vengeance, though, we have to get through its educationó and to my absolute amazement, thatís easily the strongest section of Frankenstein. Note, however, that although I do mean specifically the sojourn in the Delacey woodshed (by far the silliest, most implausible part of the story in Shelleyís telling), Iím also speaking more broadly about everything that the creature experiences from the first time Otto throws that ball until the initial confrontation between the synthetic man and its creator, when it learns at last what really makes it so different from the people who persecute it at every turn. Nothing in any other version of this story that Iíve seen brings home the loneliness of the creatureís existence as effectively as the ďfriendĒ that it makes for itself out of a potato and a cruciform stick in response to Agathaís admonition to Safie that the only way to learn fluent speech is to practice regularly on someone else. And few things Iíve seen in any other version emphasize its fundamental tragedy like the fact that this creature just canít seem to stop killing by accident, no matter how gentle it tries to be.

When the film goes back off the rails again toward the end, itís arguably a delayed side effect of something that had previously been one of its major strengths. Because the creature is so mentally unformed when it escapes from the lab, it spends much of its damned existence totally in ignorance of its creator. Frankenstein, meanwhile, forms a totally mistaken understanding of the synthetic manís nature, because he sees only the carnage that results whenever itís forced to defend itself. That reciprocal blindness pays great dividends in each parallel plot thread until they wind together at last in Frankensteinís visit to the monsterís cave. From then on, however, it becomes a hindrance, because after the incident of the bride, Frankenstein wants us to accept Victor and his creation as intimate enemies, doomed to spend the rest of their lives defining themselves by their hatred of each other, until that hatred becomes their sole source of meaning. That almost works on Frankensteinís end, since he at least has always known of the creatureís existence, and has blamed himself every time another pulped peasant was carried into his clinic. On the monsterís end, however, itís completely unearned, because the events of the final act move much too fast in-story to justify it developing such an outlook. Just a few weeks ago, the creature had never even heard of Victor Frankenstein! Thatís a real shame, because Curtis and co-writer Sam Hall managed to craft what could have been a very effective substitute for the novelís Arctic finale, which was obviously beyond the means of a production like this one. But for it to work, theyíd have needed to give the hostilities between creator and creation a longer and steadier ramp-up.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact