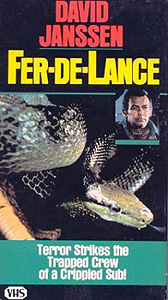

Fer-de-Lance / Death Dive / Operation Serpent (1974) *Ĺ

Fer-de-Lance / Death Dive / Operation Serpent (1974) *Ĺ

Okay, howís this for an idea? What if, in The Poseidon Adventure, Leslie Nielsen and company had had to contend with a gaggle of venomous snakes along with the rising water? Sounds pretty cool, right? Well it isnító or at least it wasnít in 1974, when it played on American television screens as Fer-de-Lance. Then again, we yanks lucked out in at least one small respect where this movie is concerned. Over in Great Britain, where it was known as Death Dive, the poor suckers had to pay money to see this stinker in the theater!

Fer-de-Lance begins annoying me almost immediately. The US Navy attack sub Fer-de-Lance has landed at Tierra del Fuego to take on supplies. Why does this annoy me, you ask? Because American attack subs (at least until the Los Angeles class entered service) were always named after aquatic animalsó not just any cold-blooded critter would do. The fer-de-lance, however, is a purely terrestrial snake. Not a big deal, I grant you, but I really donít want to see even a minor annoyance like that in a movieís first frigginí scene! Anyway, while the ship is in port, the crew are on shore leave. This brings us to a sailor whose real name wasnít revealed until long after I had dubbed him Seaman First Class Harold W. Assclown (Frank Bonner, of Equinox). Seaman Assclown is out gallivanting around with a local girl, who has taken him to a village market on the outskirts of town. Among the vendors is an old man who apparently deals in snakes, among which is a deadly fer-de-lance in a large terrarium. When Seaman Assclown realizes the snake has the same name as his ship, he gets it into his head to buy the thing from the old man. That snake isnít for sale, but it had recently hatched a brood of babies, and the old man is willing to part with those. Assclown is thrilled, and hands over five dollars in exchange for a basket full of the lethal little creatures.

Shortly after Seaman Assclown returns to the Fer-de-Lance with his new pet snakes, the ship sets off for its next mission. The sub is to report to a city on the South American mainland, and pick up a team of deep-sea divers attached to the Sealab project. This bunch is doing research on the effects of underwater detonations, and because that is a subject that interests the navy tremendously, the top brass doesnít mind lending out one of their old diesel attack boats as an underwater taxi. (Incidentally, this is another point at which I became annoyed by screenwriter Leslie Stevensís laziness in the field of rudimentary fact-checking. In his briefing for the civilian divers, the subís captain explains that the Fer-de-Lance had originally been nuclear-powered, but that it was back-fitted with diesels when it reached sufficient age that the navy no longer considered it suitable for first-line deployment. Problem number one: the Fer-de-Lanceís pennant number is 509, meaning that it was built long before the first nuclear subó the Nautilus, SSN-571. But more importantly, it simply isnít possible to replace the reactors on a nuclear sub with diesel engines and expect the ship to function as a submersible. Submarines have essentially zero margin for the redistribution of fixed internal weights; this is because they depend to a great extent upon the manipulation of water ballast for control while submerged. Nuclear reactors are vastly heavier than diesel engines of comparable output, primarily because of the necessity for thick lead shielding to protect the shipís crew from radiation. Not only that, the weight of a nuclear power plant is very highly concentrated in comparison with a diesel, meaning that even if room could somehow be found inside the hull for all the redundant machinery that would be needed to bring the new diesel plant up to the same weight as the old reactor, doing so would completely ruin the internal balance of the sub, rendering it impossible to control while submerged. Finally, thereís the matter of fuel tankage. Nuclear reactors donít burn diesel fuel, and nuclear submarines therefore donít have any internal volume set aside to accommodate it. Now granted, none of this is exactly common knowledge, but neither is it particularly difficult to uncover. Stevens just wasnít trying hard enough.) What this mission means for the Fer-de-Lance and its crew is that the sub is going to be overrun with civilians possessed of plot-point skills, who are also carrying around a shitload of explosives. All in all, that may not be such a good thing to have around when youíve already got a basket of killer snakes stashed under one of the crewmenís bunks.

Actually, if Seaman Assclown had kept his snakes under the bunk, things might not have gone so far out of control. But in order to keep them from being discovered by his section chief (needless to say, submariners are not supposed to bring poisonous reptiles onboard their vessels), he relocates them to an access conduit beneath the grating floor of the cabin he shares with the rest of his section. That conduit happens to contain some of the subís hot water pipes, and the snakes eventually get sufficiently uncomfortable to slither out and go roaming about the sub. Seaman Assclown is among the first men to get bittenó I guess thereís some justice in that, anyway. Unfortunately, the helmsman is also among that first round of victims, and he gets his while in the middle of performing a dive. His muscles go rigid while holding the diving planes to a sharp downward incline, with the result that the Fer-de-Lance hits bottom and winds up wedged between an underwater cliff face and the rubble of a rockslide at a depth of 1060 feet. Whatís more, between the snakes, the flooding, and the shock of grounding, more than half of the men onboard are killed. Only one officer, Lieutenant Whitehead (Nightwingís Ben Piazza), survives, and he is incapacitated by a moderate headwound. That leaves the top enlisted man, Chief of the Boat Russ Hogan (David Janssen, from Cult of the Cobra and Marooned), in charge, with Chief Engineer Joe Voit (Ivan Dixon) as his second in command. The scenario they face is not a promising one. Not only is the Fer-de-Lance trapped on the ocean floor with only half a crew and a pack of snakes running loose, most of the machinery spaces are flooded and it will be only about twelve hours before the air inside the sub goes bad.

Jesus, where is Irwin Allen when you need him? Sure, most of his disaster movies bit the big one, but at least he had a certain feel for the material, so that they often bit the big one in an entertaining way. Not so Fer-de-Lance. Not even the addition of killer snakes can stop this movie from being dulló largely because those snakes (despite being referenced in the title of the film) are treated very much as an afterthought. In fact, for most of the movie, they arenít even an issue, because Hogan figures out very quickly that turning off the heat inside the sub will make it too cold for the reptiles to function. It isnít until the vessel is freed from its undersea prison and returns to the warmer waters near the surface that the creatures wake up again and resume their function of giving Fer-de-Lance some point of distinction from the droves of better shipwreck movies that were clogging the theaters at the time it was made. I canít for the life of me understand why the filmmakers would do it this way. I mean, if youíd come up with a new and (to you at least) exciting angle with which to snazz up a shopworn premise, donít you think youíd, I donít know, make some kind of use of that angle?! I know I personally would exploit the hell out of it. So what, then, do you suppose the makers of Fer-de-Lance were thinking?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact