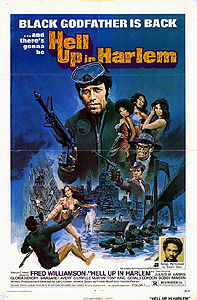

Hell Up in Harlem (1973) -**

Hell Up in Harlem (1973) -**

There are exceptions, of course, but in my experience, the more elegantly constructed and seamlessly self-contained a movie is, the less satisfying its sequels are likely to be— and naturally, this tendency is only exacerbated by brief turnaround times between films. Consequently, Hell Up in Harlem was facing a serious uphill struggle from the very beginning. Black Caesar had probably the tightest, most loose-end-free storyline of any blaxploitation picture ever. It charted the career of its central character from the inception of his life of crime, through his rise to dominance over Harlem’s criminal underworld, and all the way to his final and seemingly irrevocable downfall; if ever a film could be said to have offered absolutely no foothold for a potential sequel, Black Caesar was it. But when it went through the roof early in 1973, American International Pictures boss Samuel Z. Arkoff got in touch with Larry Cohen, the movie’s writer/producer/ director, and basically told him to get to work on a sequel right that minute. Making the task of continuing a story with no logical means of continuation even more difficult, Cohen was already hard at work writing and directing It’s Alive for Warner Brothers, meaning that he would have very little time on his hands in which to attack the almost intractable problem. Indeed, when the first day of Hell Up in Harlem’s shooting schedule arrived, the script was only half-completed, little more than a plot outline with a few key scenes here and there fleshed out into something approximating their final form. Anyone who gets the impression, watching Hell Up in Harlem, that no one involved in making it had any very clear idea of how it was all supposed to fit together is therefore right on the money. To an even greater extent than usual, the sequel to Black Caesar was an unabashed product of pure greed, and not even Cohen himself has much to say in its defense.

I can think of no surer measure of the original movie’s integrity than the fact that Hell Up in Harlem has to spend fully half an hour undoing its predecessor’s conclusion before it is able to take up the thread of its own narrative. In fact, a considerable fraction of the first act consists of footage lifted directly from the previous film. We see again the assassination attempt on Harlem crime kingpin Tommy Gibbs (Fred Williamson, whose prior commitments— he was busy every Monday through Friday making That Man Bolt in Los Angeles— added yet another wrinkle to Cohen’s logistical nightmare), in which a corrupt New York City cop gut-shoots him in the middle of a crosswalk on 57th Street. We see again the wounded Tommy’s desperate escape by taxicab, in which he evades the men sent to finish him off by bribing the cabbie to drive down the sidewalk instead of fighting through a traffic jam in the approved manner. We see again Tommy’s bloody retrieval of the mafia ledgers with which he held the law at bay for years, blackmailing the crooked city authorities with a detailed record of some twenty years’ worth of underhanded dealings with the mob. And we see Gibbs once more as he staggers, still badly bleeding from the gunshot in his belly, into the ruins of the tenement block where he grew up, and where the earlier movie ended with him being beaten and robbed by a gang of vicious street kids. But this time, intercut with all that recycled action is a bit of new footage which puts a slightly different spin on events. We learn that the man behind the assassination attempt was not Tommy’s old nemesis, McKinley, but the even more exalted District Attorney D’Angelo (It Happened at Lakewood Manor’s Gerald Gordon). We learn that the information necessary to pull off the hit was provided by Tommy’s embittered ex-girlfriend, Helen (Gloria Hendry again). And most importantly, we learn that Gibbs placed a phone call to his estranged father (Julius Harris, also returning to his old role) before heading back to his demolished childhood home, arranging for the old man to meet him there. As a result, we now have a minimally defensible excuse for Gibbs to survive getting both shot and beaten in rapid succession, and Hell Up in Harlem thus has a minimally defensible excuse for existing in the first place.

The first order of business, naturally, is to get Gibbs to a hospital. After hiding the mafia ledgers inside a pile of stones in the park near the old house, Thomas Gibbs Sr. gets on a pay phone to call Zach (Tony King, of Cannibal Apocalypse and Gordon’s War), one of the few remaining members of Tommy’s organization whom the younger Gibbs believes to be still loyal to him. Zach comes on the run with about ten other men, and the gangsters essentially take Harlem Hospital hostage for as long as is necessary for a surgeon to repair the boss-man’s injuries. The gangsters’ safe-conduct out of the hospital is secured when Thomas Sr. places a call to D’Angelo, informing him that Tommy has the ledgers back in his possession. Tommy’s dad initially figures that his role in the raid on the hospital will constitute the whole of his underworld involvement, but just a few days later, he is taken into custody by the police, and led up to the roof of a tall building. There D’Angelo pumps him for information regarding his son, and when the old man professes not to know anything about either Tommy or the ledgers, the district attorney walks off leaving a few of his crooked cops with instructions to kill Mr. Gibbs. Gibbs is awfully tough for an old guy, though, and he gets the better of two of D’Angelo’s men before Zach (who had been assigned, unbeknownst to anybody, to guard Gibbs Sr.) pops up to finish the job. With the blood of two policemen now on his hands, Gibbs the elder now has little choice but to throw his lot in with his son. In fact, after handling a bit of important unfinished business during Tommy’s convalescence, Big Papa (as the soundtrack soon dubs him) rises to become his son’s right-hand man.

The biggest piece of that unfinished business concerns Helen. Gibbs knows (don’t ask me how) that she was in on the plot to kill him, and that she was somehow and for some reason involved in the much more successful scheme to assassinate Joe Washington, Tommy’s former best friend, with whom Helen was living, and whose kids she evidently bore through the magic of retroactive continuity. As his revenge, Tommy sends Big Papa to abduct the two children, and bring them back to Gibbs HQ so that he can raise them as his own. Even Larry Cohen agrees that this subplot doesn’t make a lot of sense, and those of you who appreciate things like logic and dramatic honesty will doubtless find the whole business even more annoying when you see how it pays off in the final reel. Anyway, between the kidnapping and a couple of bloody hits on mobsters we’ve neither seen nor heard of before (but who we are nevertheless assured were key figures in the plot to bring Tommy down), Gibbs and his dad are eventually able to reset the balance of power in Harlem to approximately its status during Black Caesar’s second act. Then, at long last, Hell Up in Harlem can get down to business.

And what sad, weedy business that is, too. D’Angelo, knowing full well that Gibbs and his dad together are more than a match for him and his mafia cronies, looks for ways to split up the father-son tag-team. He finally settles upon a plan to exploit the two men’s sharp difference of opinion over Helen— Big Papa despises her as the woman who betrayed his son, but Tommy has enough residual love for her that he lets it be known that she is under his personal protection, and that anyone in Harlem who harms her will have to answer to him. D’Angelo turns the increasingly ambitious Zach against his employers, hiring him to kill Helen and frame Big Papa for the crime. This comes at a time when Tommy, having recently taken up with a woman named Jennifer (Margaret Avery, from Terror at Red Wolf Inn and Cyborg 3: The Recycler) who works at the church where his old buddy Rufus (still D’Urville Martin) preaches, was already strongly considering retiring from the gangstering business. Partly for that reason and partly to get back at his father by leaving him to fend for himself in Harlem, Tommy packs up Jennifer and the stolen kids, and flies out to Los Angeles. Gibbs therefore isn’t around to intervene in the showdown between Zach and his father, and he finds himself cut off from all of his resources as a crime boss when the victorious Zach decides to come after him even on the other side of the country— and that’s to say nothing of the trouble D’Angelo will be able to cause him. The resulting battle pitting Tommy Gibbs alone against the criminal organization he himself created has a lot more in common with the macho fantasies of the stereotypical blaxploitation movie than it does with the grim and gritty realism of Black Caesar.

I have to hand it to Larry Cohen— he harbors very few illusions about his work, and when he turns out a dud, he doesn’t hesitate to admit it. Hell Up in Harlem is very much a dud, and while that was probably inevitable for the reasons I’ve already described, it’s still a shame that a movie as bad as this one had to be made as a follow-up to Black Caesar. Its main storyline is tired and anemic, realizing none of the promise in what should have been the central thread of the plot: the curious chain of circumstance that causes the aged and formerly law-abiding father of a notorious gang leader to become an underworld overlord himself. Instead, the rise and fall of Big Papa is treated as a mostly disposable sideline, intended primarily to give Tommy some motivation for ass-kicking after he’s already basically sat out a good two thirds of the movie. Worse still, about half of the running time has little or no apparent connection to either main character’s story arc. Far too many scenes were included solely because Cohen happened to have found a prime shooting location at a time when he still had only the vaguest idea of what Hell Up in Harlem was going to be about, and knew only that he had to fill up the running time somehow. Others owe their existence to an admittedly understandable perception on Cohen’s part that he would be expected to outdo certain specific incidents from the previous movie, and nearly every one of those attempts at topping himself fails spectacularly. The worst is the final clash between Gibbs and D’Angelo, which was meant to recall the face-off against McKinley in the original film. (As Cohen puts it on the audio commentary to the Soul Cinema DVD release of Hell Up in Harlem, “We knew we had to top that scene— and boy, we sure didn’t!”) The McKinley incident was one of the most powerful single scenes in the whole 70’s blaxploitation canon, tying together all the different themes and plot-threads of the movie and wrapping them up in a pitch-perfect anti-racist revenge fantasy. D’Angelo’s fate is less satisfying, first because of a failure of imagination (Gibbs did McKinley up in blackface and forced him to sing “Mammy” before beating him to death with a shoe-shine box; D’Angelo merely becomes “the first white man ever to be [lynched] by a nigger”), secondly because he’s a much less significant figure in Tommy’s life than McKinley had been, and thirdly because the final confrontation hinges upon an interpersonal bond of which we have hitherto seen little or no evidence.

As big a problem as the visibly rushed and almost totally incoherent script is, however, there is another defect in Hell Up in Harlem that might be even more crippling in comparison with its predecessor. Throughout the movie, there is a campy, almost parodic tone which is utterly at odds with Black Caesar’s abrasive honesty. The old Tommy Gibbs was at best an anti-hero; he was a hardened criminal with no scruples at all, and the first movie never let you forget that. The new Tommy Gibbs is practically a cartoon, with a catchphrase or a wisecrack forever on the tip of his tongue and a stereotypical code of gangster’s ethics of the sort which even the makers of Japanese yakuza films were coming to see as obsolete and implausible by the early 1970’s. Not only that, a great deal of the action in Hell Up in Harlem is just plain wacky. Early on, Gibbs leads an amphibious commando raid against a rival’s headquarters on “an unnamed island in the Florida Keys”— with his gangsters dressed up in full Navy SEAL frogman regalia no less! (Incidentally, keep an eye out for the bikini girl who tangles with Tommy and several of his men in the mobster’s garden. That was Fred Williamson’s real-life girlfriend.) Later, there is a drawn-out chase sequence in which Tommy pursues Zach from the coal depot where they’ve just fought a pitched battle (because Cohen’s mother knew the owner, and could thus get the director an unusual shooting location for free) to JFK airport; the two enemies then board separate planes bound for Los Angeles, traverse the complete breadth of the United States, and resume their chase on foot at LAX. It’s as gleefully absurd as anything you’ll see in a blaxploitation movie made without the involvement of Rudy Ray Moore. If it were possible to take this movie seriously as a continuation of Black Caesar, the second film would make an absolute mockery of the first. The one saving grace is that it isn’t possible to take Hell Up in Harlem seriously, at that or any other level. Hell Up in Harlem, despite benefiting from Cohen’s usual technical skill and creativity as a director, is so thoroughly bungled in every other respect as to become little more than a gigantic joke, and truth be told, I kind of wish Sam Arkoff had entrusted the project to some nitwit like William Sachs instead of bringing back Cohen. It might have been more enjoyable as an out-and-out train-wreck.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact