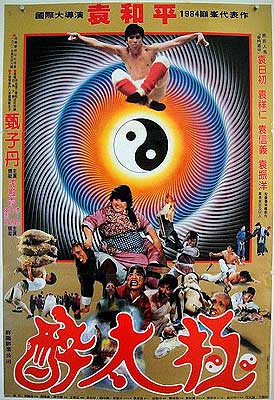

Drunken Tai Chi / Drunken Tai Chi Master / Laughing Tai Chi / Super Fist / Siu Tai Gik / Xiao Tai Ji (1984) ***½

Drunken Tai Chi / Drunken Tai Chi Master / Laughing Tai Chi / Super Fist / Siu Tai Gik / Xiao Tai Ji (1984) ***½

Humor is notoriously hard to translate, and comedies often don’t travel well from one culture to another. The trouble is that jokes don’t and can’t exist in a vacuum. Comedy, at bottom, is about incongruity and expectations, both of which depend heavily on the structures of assumptions that we’re really talking about when we say “culture.” If we don’t perceive or understand the norms being violated, then we’re not going to get the joke. Occasionally, though, there’s a countervailing process at work. Sometimes foreign humor becomes funny because it doesn’t translate; sometimes other cultures’ comedy works because the gags coincidentally violate our norms, or because it comes across as so endearingly bizarre that we can’t help but laugh even though we don’t properly understand it. Drunken Tai Chi is the strongest example of the latter phenomenon that I’ve seen in some time. No one in the West would make a movie like this, and the bewilderment Drunken Tai Chi is sure to inspire in unprepared Occidental viewers might actually make it funnier than it was intended to be.

The root of the conflict here is the rivalry between Ta Sha (Mandy Chau, from Taoism Drunkard and Kung Fu Vampires), who’s kind of a show-off, and Chan Chuen Chung (Donnie Yen, of Iron Monkey and Holy Virgin vs. the Evil Dead), who’s kind of a jerk. Every time Ta Sha indulges his attention-seeking proclivities, Chuen Chung makes a point of sabotaging his efforts, showing him up by displaying the same skill in a more perfected state, or otherwise making a fool of him. It isn’t just Ta Sha that Chuen Chung treats thusly, either; the latter lad’s stick-in-the-mud brother, Yu Ping (Yuen Yat Chor, from Buddhist Fist and Young Taoism Fighter), frequently comes in for much the same sort of hazing. Oh— and I should probably mention that Chuen Chung, rather than either of his habitual victims, is going to be the hero of this story. Yeah. The callow little prick isn’t totally unsympathetic, however, because his dad (Li Kun, of The Bloodthirsty Dead and Eagle’s Claw and Butterfly Palm) so obviously favors Yu Ping that it becomes easy to see Chuen Chung’s jerkitude as a poorly chosen coping mechanism.

Still, there’s only so long you can bully someone before you run the risk of them snapping on you and making with the Righteous Vengeance— and that goes double if you happen to exist in a kung fu movie. Ta Sha’s snapping is a sight to behold, let me tell you. Rounding up a couple of his friends, he lays an ambush for Chuen Chung in a little-traveled alley one night, and attacks him not only with kung fu, but also with fireworks! Unfortunately for Ta Sha, Chuen Chung’s fighting skill proves superior (much like Chuen Chung’s everything else), and the put-upon show-off winds up being blown sky high by his own pyrotechnics. Although Ta Sha’s physical recovery is as quick as any ever made by Wile E. Coyote, he is subsequently so crippled by shell shock that he can’t so much as leave his bedroom. His father (Don Wong, from Bandits, Prostitutes, and Silver and Ten Brothers of Shaolin) knows full well who’s responsible, and plots an extremely thorough revenge. He hires the mute assassin Iron Steel (Yuen Shun Yee, of One-Armed Swordsman and Drunken Master) to kill not only Chuen Chung, but the entire Chan family. The main target isn’t at home when Iron Steel comes by to fulfill his commission, but he doesn’t let that deter him from getting a strong start on the job. When Chuen Chung returns from a night on the town, his pockets bulging from betting on his own prowess at a game that we might think of as Chinese arm-wrestling, he finds the house burned to the ground, with the extra-crispy bodies of his father and brother amid the wreckage.

Chuen Chung understandably falls into rather a funk after that. Of course, since this is a kung fu movie, falling into a funk entails getting into lots of fights with random strangers, including an unbelievably graceful and athletic fat woman (Lydia Shum Tin Ha, from Oriental Playgirls and The Invincible Eight) and a hard-drinking puppeteer (Yuen Cheung Yan, of Battle Wizard and The Oily Maniac) who turns out to be a master of tai chi. (I should probably clarify here that “tai chi” in this context refers to the original fighting technique, rather than the fitness and meditation regimen derived from it which is more familiar in the West today.) Those two characters— husband and wife, as it happens, although Chuen Chung tangles with them separately— eventually take the now homeless lad in as a handyman, which leads in a somewhat roundabout way to him studying tai chi under the puppeteer’s tutelage. That’s going to come in handy, because Iron Steel hasn’t given up looking for Chuen Chung, and tai chi (a “soft” style in Chinese martial-arts parlance) is inevitably the one effective counter to the assassin’s kung fu (which, as his name implies, is the hardest of “hard” styles).

The means whereby Chuen Chung and Iron Steel cross paths for the final showdown is probably the best encapsulation of how mind-bending Drunken Tai Chi can be for audiences steeped in the assumptions of Western filmmaking, and unfamiliar with those of its Chinese counterpart. The assassin has a child, a little boy of perhaps three years, and Chuen Chung happens to witness him being kidnapped off the street by bandits we’ve never seen before and won’t be seeing again. Chuen Chung has no idea who the kid is, you understand. He jumps in to rescue him simply because that’s what any respectable kung fu master ought to do under the circumstances. Iron Steel, meanwhile, is frantically searching the marketplace for his son, not having seen the abduction go down, and therefore totally clueless about what might have become of him. The first face-to-face meeting between the antagonists thus takes the form of the target returning the assassin’s child to him. In a Hollywood movie, that would surely mean the end of the conflict, or at least provide a mechanism for its peaceful resolution. Whether on the spot or after an interval of dramatic soul-searching, we could expect Iron Steel to break his contract with Ta Sha’s father in gratitude for Chuen Chung’s heroism. But that’s not what happens in Drunken Tai Chi. Here, a contract is a contract and an assassin is an assassin, even if he’s also a doting father, and the showdown between Iron Steel and Chuen Chung occurs right on schedule. At the same time, though, that final fight, like all the ones leading up to it, is treated at least partly as a slapstick comedy set-piece, despite being not only a literally deadly serious affair, but also in some sense a tragic one. These are not our storytelling norms, this matter-of-fact admixture of violence, humor, and pathos, and Drunken Tai Chi becomes pleasantly disorienting for Western viewers in part because of it.

Digging a bit deeper, and returning to the specific subject of Drunken Tai Chi’s sense of humor, the divergence from Occidental expectations lies less in what this movie plays for laughs than in how. In Europe, North America, and British Oceania, it isn’t unheard of for a movie to ask us to laugh along as it murders its protagonist’s family and leaves him homeless and destitute, but it would take a black comedy indeed to attempt such a thing. The mood of Drunken Tai Chi doesn’t read as black, though. Indeed, it’s downright sunny! Under our rules for light comedy, people’s actions don’t generally have serious consequences, especially when they very obviously would in the real world. You might even argue that those artificially lowered stakes are the very thing that defines light comedy in the West. Pick a random film featuring the Bowery Boys, Will Farrell, or any of a hundred comics from the years in between, and you’ll see poverty, homelessness, crime, substance abuse, family dysfunction, and even outright violence treated as fundamentally harmless chuckle-generators. To steal a line from Patrick Swayze in Road House, Occidental light comedy posits a world in which pain don’t hurt. Drunken Tai Chi, in contrast, is all about serious consequences. Its whole second and third acts are motivated by Ta Sha’s post-traumatic stress disorder and his father’s determination to make Chuen Chung pay for inflicting it. As if that weren’t enough of a downer, the denouement has Iron Steel pushed by his code of professional ethics to attempt the murder of a boy whom he by then has every reason to consider his friend. And yet this movie somehow never seems like a downer at all.

Drunken Tai Chi is just as startlingly weird in its approach to physical comedy, which you’d think would be something of a universal language. You can see it most clearly in the handling of the puppeteer’s wife. One look at her, and you’ll assume that she’s here mainly to serve as a delivery system for fat jokes. That’s true in a very general sense, but this movie’s fat jokes aren’t like most others you’ve probably encountered. Instead of the usual gawking cruelty, they’re all premised on the fact that despite her huge size and ungainly appearance, Lydia Shum is as fast, as nimble, and as acrobatic as even Donnie Yen himself. It’s both very refreshing and an awesome sight to behold.

Of course, Shum’s performance and the thinking behind it are surprising only in the moment. In retrospect, they seem practically inevitable given some of the names in the opening credits. Drunken Tai Chi bills itself as a “Yuen Clan” film— Yuen as in Yuen Woo Ping, Yuen Siu Tien, Yuen Shun Yee, and so forth. These are the people who practically invented the kung fu comedy, and in Drunken Tai Chi even more than Drunken Master, they demonstrate what’s missing from far too much slapstick: a notion of choreography comparable to that which the Yuens so famously applied to martial arts combat. The fights in this movie are funny was well as being dazzling displays of strength, agility, and bodily control. And similarly, physical comedy set-pieces like Lydia Shum carrying a gigantic bundle of raw cotton across a plank bridge that shouldn’t possibly be able to support her weight (let alone that of her cargo) are amusing precisely because they’re as expertly timed and coordinated as the fisticuffs. Tie those techniques together with the inadvertent culture-shock humor we’ve already discussed (as in the astonishing fireworks battle between Chuen Chung and Ta Sha), and they yield something truly magnificent.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact