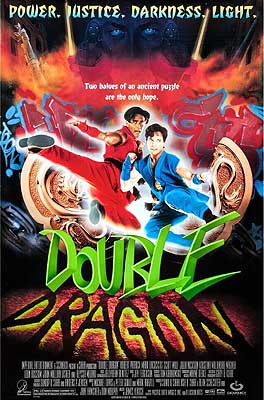

Double Dragon (1994) -**½

Double Dragon (1994) -**½

I don’t understand why there weren’t any video game movies in the 80’s. Sure, there were movies about video games— about creating, playing, or being trapped inside them, or in which video games and the people who played them drove some aspect of the plot— but the earliest direct adaptation of a game that I can think of was 1993’s Super Mario Bros. Don’t try to tell me it’s because 80’s video game premises weren’t sophisticated enough to build a story around, either. If Pac-Man could support a weekly Saturday morning cartoon for the equivalent of three quarters of a season, then surely Defender (aliens attempt to conquer Earth using flying combat cyborgs created from captured humans) or Wizard of Wor (space sorcerer makes captive astronauts fight to the death in an underground maze filled with hideous monsters) could support an 85-minute B-picture. What doesn’t surprise me is that when video game movies did finally start appearing, none of them were any good, nor did they reflect more than the dimmest understanding on their creators’ parts of what the games’ fans might want from a film adaptation. Most of all— and this persists even today, despite video games getting much more respect within mainstream pop-culture— the makers of video game movies seem not to trust the source material. Take Double Dragon as an example. The premise of the arcade game was admittedly fairly slender: karate-fighting brothers must rescue their girlfriend from a vicious street gang in a blighted and lawless city. Plenty of action movies have started with less, however, and a straight Double Dragon adaptation would have made a fine basis for a third Walter Hill urban decay fantasy, doing for the 90’s what The Warriors and Streets of Fire did for the 70’s and 80’s. The Double Dragon movie we actually got does a bit of that, to be sure, but the producers wanted more. So in addition to operating as a down-market Walter Hill tribute, it’s also a kiddied-up, post-apocalyptic, pseudo-cyberpunk dystopia, informed equally by bullshit Chinese mysticism and RoboCop-ian social satire. It’s a ridiculous mess, but an entertaining one.

First, the bullshit Chinese mysticism. Thousands of years ago, an embattled king put his life essence into a golden amulet depicting two entwined dragons. Whoever wore this Double Dragon would become an invincible warrior, with absolute control over the powers of body and soul. After the amulet’s immediate purpose was served, however, the hero who wielded it decided that it was too much for any mortal to be trusted with, and broke it into two pieces. The halves were then hidden away, far apart from each other, but the legend of the Double Dragon lives on. Would-be heroes and would-be villains alike have sought to reunite the medallion over the ensuing millennia, and unfortunately the current seeker falls into the latter category. International tycoon Victor Geissmann (Robert Patrick, from The Faculty and Terminator 2: Judgment Day) is widely regarded to be the richest man in the world, but even that isn’t enough for him. The kind of power Geissmann wants can’t be bought, traded for, or even won at the ballot box. No, the only way to become a god-king is to make yourself one— and to give yourself a more pretentious name, while you’re at it. Geissman likes the sound of “Koga Shuko.” (“Elegant Scheme” would be my best guess, although the Japanese mania for homophones makes it impossible to be sure without kanji for verification.) Naturally, the first bit of power that Geissmann intends to seize is that of the Double Dragon, which should make it much easier for him to seize all the rest later. That plan hits a snag, though, when his henchmen, Lash (Kristina Wagner), Huey (Jeff Imada, of Hyper Space and The Crow), and Lewis (Al Leong, from Big Trouble in Little China and Escape from L.A.), raid the Tibetan monastery where it’s supposed to be kept (stood in for by a picturesque but extremely un-Tibetan-looking mountain in the Philippines), and find only the “soul” half of the artifact.

And now for the post-apocalyptic, pseudo-cyberpunk dystopia. In the far-flung year 2007, Los Angeles is no more, destroyed a decade earlier in the Great Quake. New Angeles, the city that has risen from the ruins, is a Jekyll-and-Hyde sort of place, upwardly mobile enough for a man like Geissmann to maintain a business headquarters there, but ruled all through the night by warring street gangs. That actually represents an improvement in the city’s fortunes, too. Ten years ago, the gangs were the only law there was, and it took a formal truce negotiated by Police Chief Delario (Silver Bullet’s Leon Russom) to make them cede the hours of daylight to decent folks who wanted a functioning society. In practice, that means a strict curfew for everyone in New Angeles who isn’t a violent criminal, and no police presence on the streets after sundown. Still, there are those who seek the full restoration of order, and the most hopeful sign in that direction, paradoxically, is a vigilante youth army calling itself Power Corps, dedicated to fighting the outlaw gangs on their own terms. Chief Delario doesn’t realize this, but Power Corps’s leader is his own daughter, Marian (Alyssa Milano, from Embrace of the Vampire and Poison Ivy II).

And now, at last, for the actual story. Shortly before curfew one evening, brothers Jimmy and Billy Lee (Mark Dacascos, from Brotherhood of the Wolf and The Island of Dr. Moreau, and Scott Wolf, from nothing terribly interesting), are competing in some manner of martial arts tournament. They’ve made it all the way to the finals, but then Billy does something stupid and gets them disqualified. As if that weren’t bad enough, that last fight spins out long enough that curfew is in effect by the time the brothers and their guardian, Satori Imada (Julia Nickson, of Devil in the Flesh and Amityville: A New Generation), are on their way home. The route back to the defunct theater where Satori and the boys squat runs through territory controlled by the Mohawks, and our heroes have the foul luck to attract the attention of the gang’s leader, Bo Abobo (Nils Allen Stewart, from Fist of the North Star and CyberTracker II). Abobo may be extremely stupid, but he’s also extremely persistent— and all the steroids he shoots up have made him almost superhumanly strong. Jimmy and Billy really don’t want to have to fight him. It looks like they’re not going to have any choice in the matter when Abobo herds them into a blind alley, but Power Corps is out in force tonight, and not even Abobo is tough enough to take on that many opponents singlehanded. Satori and her wards make it back to the theater without further incident, although the brothers’ macho pride is wounded somewhat by their need for Marian’s intervention.

Abobo isn’t merely the leader of the Mohawks. He’s also in the bag for Victor Geissmann, providing muscle whenever the tycoon needs it in New Angeles. At their next meeting, the gangster mentions his recent run-in with Satori and the Lee brothers. Geissmann is intrigued to hear about it, because he and Satori know each other somehow. In fact, Geissmann knows that she was the last person to have seen both halves of the Double Dragon together. Maybe she can tell him where the “body” half is now— hell, maybe she actually has it! At the very least, it’s worth it to Koga Shuko to launch a strike on the old theater, and not taking any chances, he brings Bo Abobo along after dosing him with an experimental super-steroid that basically turns him into the Toxic Avenger.

No one on either side is satisfied with the outcome of the resulting clash, except insofar as it confirms Geissmann’s suspicions about where to find the other half of the Double Dragon. Satori is killed and the Lee brothers’ home is destroyed in the fighting, but Billy is able to hang onto Satori’s half of the amulet, and Abobo falls into the clutches of Power Corps (who attempt to domesticate him by force-feeding him spinach, of all things). Koga Shuko comes away with the idea that a major hench upgrade is in order. He unites all the gangs of New Angeles behind him by killing the leader of the Maniacs (Michael Berryman, from Cut and Run and The Hills Have Eyes, Part 2), the most powerful of the bunch, in single combat, and orders them to abrogate the truce with the authorities. With the whole city in the grip of unprecedented street violence, there should be nowhere for the Lees to hide. What Geissmann fails to recognize is that killing Satori was the one thing that could turn a couple of fuck-ups like Jimmy and Billy into a genuine threat. It was also the one thing that could make them put aside their hang-ups and enter into full-fledged alliance with Power Corps. So while Koga Shuko may have an army at his disposal, so do his enemies— and that’s before taking into consideration the possibilities of cooperation between Power Corps and Chief Delario’s besieged police.

What you’ve just finished reading really only hints at what makes Double Dragon so much stupid fun, however, because most of this movie’s entertainment value lies in its production design, its off-kilter sense of humor, and its mission as a comedy for eleven-year-old boys. The costumes especially are a hoot, and remarkably, the Chinese-influenced, color-coordinated vest-and-pajama ensembles taken directly from the game to signify the Lee brothers’ ascension to Double Dragon status are about the most tasteful on offer. Just like in The Warriors, each of the gangs has its own distinctive uniform: punk garb for the Mohawks, splatter-dyed pastel-and-neon workout gear for Power Corps, a nearly indescribable post-apocalyptic peasant look for the Maniacs, and so forth. Marian wears a variation on the main Power Corps style in which her acid-washed mom jeans are cut off at Daisy Duke length, but then the lower halves of the legs (beginning just above the knees) hang suspended from an industrial-strength garter belt. Geissmann and his minions dress in what looks like a cross between a gi and a Mao suit, with a bit of individualization in the details. Lash’s version is more form-fitting than the men’s, naturally, while Huey’s and Lewis’s outfits have some extra elements that suggest busboys at a Chinese restaurant, in keeping with their subordinate positions. What really makes Geissmann visually memorable, though, is his punk-dyed flattop-cum-pompadour and Satanic goatee. Robert Patrick’s performance is turned up to maximum as it is, but it goes to eleven with that hairdo and beard to back it up.

Another of Double Dragon’s visual oddities is its frequent recourse to computer animation, seemingly for no reason but to remind us that the source material was a video game. I don’t mean the primitive CGI used to portray Geissmann’s amulet-imparted ability to turn himself into a shadow, which is diegetically reasonable, and probably could have been managed in no other way. Rather, I’m talking about all the times when this or that character must consult an electronic screen of some kind, at which point the film can be counted upon to indulge its era’s silly fascination with virtual reality. The most memorable such moment comes during the first clash with the Mohawks, when the Lee brothers bring up what I have to assume is Bo Abobo’s Grindr profile on the internet terminal in their station wagon before deciding whether to fight him or to flee, and Abobo counteracts the boys’ smokescreen defense by piloting his SUV in VR mode. The computerized interludes are generally presented filling the full screen, and are so out of step with the rest of the film as to be almost the sole reason why I felt compelled to add “pseudo-cyberpunk” to my one-liner description of Double Dragon above.

The movie’s sense of humor, meanwhile, is what led me to reference RoboCop. Some of the gags are explicitly riffs on that film, like the scene-transition clips from a vapid TV news show in which Vanna White and George Hamilton play themselves as the dim-bulb anchors. But more often, it’s simply a question of Double Dragon aping Paul Verhoeven’s blackly wry approach to futurism and sarcastic attitude toward the coarsening of American culture. This movie’s vision of law enforcement cowed into surrendering the night to banditry isn’t so far from RoboCop’s police department demoralized by privatization, corporate interference, and inability to match the numbers or firepower of the criminal gangs. The trash-burning engine of the Lees’ car feels of a piece with horrible consumer products like lethal anti-theft systems, carcinogenic hyper-sunscreen, and the 6000 SUX. Bo Abobo’s transformation upon injection with Geissmann’s super-steroid recalls equally the effects of a toxic waste bath on Clarence Boddicker’s right-hand man and Cain’s reincarnation as the titular cyborg in RoboCop 2. The very name New Angeles is an obvious echo of Old Detroit. But because of the presumed audience, Double Dragon is both broader and cornier in its humor than Verhoeven would have tolerated, coming closer to RoboCop 3 than to either of its predecessors. Virtually every character is addicted to moronic one-liners, not a few of which are jarring in-jokes on things the performers had done elsewhere. Witness Lash quipping, “Now who’s the boss?” upon gaining the upper hand in combat over Marian Delario (Alyssa Milano, remember). This is also the kind of movie in which not only are there paired characters named Huey and Lewis, but someone will actually ask them at one point if there’s been any news. The latter is probably the most groan-worthy of Double Dragon’s gags, so it’s fitting that Huey and Lewis should also figure in what is unquestionably its best to make up for it. In the final scene of the film, the Lee brothers, Marian, and the more or less reformed Bo Abobo speed down the street, passing the now jobless thugs as they hold up a cardboard sign reading, “Will hench for food.”

Double Dragon is at its strangest, goofiest, and most enjoyable, though, when its status as a kids’ movie working within three traditionally R-rated genres comes sharply into focus. Normatively, urban blight thrillers, post-apocalypse action flicks, and chopsocky had all been aimed at “adult” audiences before the 1990’s, at least in the United States. That’s not to say that pitching one of those things (or in this case all of them) at a younger crowd is inherently ridiculous, but Double Dragon plays around with the tropes of its several genres in ways that plainly assume audience familiarity with them. That is, it’s one of the few films I’ve seen to acknowledge the open secret that since the advent of cable TV and home video, kids much younger than seventeen were habitually watching R-rated movies, and thus could safely be presumed familiar with drive-in/grindhouse fare like The Road Warrior, Death Wish 3, and Enter the Ninja. It’s admirable, really, that lack of the nigh-universal hypocrisy insisting that movies tailored directly to the tastes of hormone-addled adolescents are being watched exclusively by people seventeen and up, but the very ubiquity of that attitude makes it feel like something has gone wrong in its absence. And the truth is that Double Dragon often goes for kid appeal in ways that make it inappropriate for anyone older. That’s odd, because one of this movie’s writers— Paul Dini— had been busy since 1992 as one of the main creative forces behind “Batman: The Animated Series,” one of the decade’s foremost successes in reaching broadly across the age spectrum. It’s worth noting, however, that Dini claimed only story credit here; the screenplay proper is attributed to Michael Davis and Peter Gould. It may be that some of Double Dragon’s tonal mismatches stem from Dini envisioning something that children, teens, and adults could all enjoy equally, but that point being lost on the more directly involved creators. Be that as it may, this is the movie for you if you’ve ever found yourself wishing that Golan and Globus had made something for Nickelodeon.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact