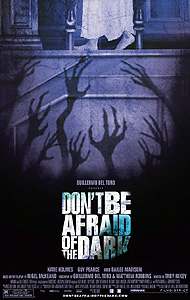

Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark (2010/2011) ***

Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark (2010/2011) ***

I can’t tell you how excited I was to learn that Guillermo Del Toro was working on a remake of Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark. The original version has been for many years among my favorite products of the curious efflorescence of high-quality made-for-television horror movies in the 1970’s, but it wasn’t so good that I couldn’t imagine a very astute filmmaker improving on it. Horror on the small screen was always hobbled by restrictive rules of engagement, and nothing punctures a suspenseful mood like breaking for commercials, even when the commercials themselves have been excised. Del Toro, meanwhile, certainly has astuteness covered. His English-language movies have been of lesser caliber on the whole than those written and shot in his native Spanish, but even the weakest of the lot have had something to recommend them. What’s more, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark was a fairy tale at heart, and Pan’s Labyrinth showed to breathtaking effect what Del Toro can do with that sort of subject matter. Reports that the remake would be shown from a child’s point of view offered further encouragement, suggesting both that it would be emphasizing the fairy-tale aspect even further, and that it would not be hampered by what might otherwise become a crippling characterization problem: the attitudes and behavior toward the adult Sally that made the male lead merely a jerk in 1973 would turn him into a cartoonish villain in the 21st century. My enthusiasm was dampened a bit by the news that Del Toro would not be directing the new Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark himself (turning over the folding chair to some totally unheard-of guy named Troy Nixey), but only a bit. Del Toro would still be producing, after all, and as we see from the career of Roger Corman, producers with directing experience often leave just as deep a mark on their films as the credited directors. Del Toro would have a hand in writing the screenplay, too, which was another point in the new movie’s favor. And of course there was the fact that Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark ultimately went the better part of a year without securing a distribution deal. That might sound bad to the un- or only partially initiated, but in the realm of medium-budget horror cinema, it’s frequently a promising sign; such tends to be the fate of movies deemed too something (too intense, too gory, too provocative, too just plain weird) for mainstream audiences by skittish studio bosses. I say all this to emphasize that my disappointment with this film has more to do with my expectations going in than with the quality of the product itself. Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark is a creditable piece of work by nearly any standard, equal on the balance to the original version. It’s just that this was one of those rare cases where equaling the original seemed like the least we could reasonably hope for from a remake.

I can’t decide whether the opening scene is a canny bit of suspense-building or one of this picture’s more serious missteps. In it, we are introduced (well, sort of) to renowned 19th-century wildlife painter Emerson Blackwood (Garry McDonald, of Stone and Picnic at Hanging Rock) as he toils over some mysterious project in his studio in the cellar of his gothic-as-fuck Rhode Island mansion. It turns out he’s working on a booby trap for the maid (Edwina Ritchard). Needless to say, tripping the help down the basement stairs is an odd thing for even a rich eccentric to do, but Blackwood has his reasons. The furnace in his studio improbably communicates with a natural chasm leading into the bowels of the Earth, and it seems that whatever lives down there has taken Blackwood’s son. Evidently the denizens of the chasm did this because they wanted the boy’s teeth, and Emerson is hoping that they’ll accept both his and the maid’s in exchange. No such luck. The kidnappers from the deep are after primary teeth, and they have a strict “no substitutions” policy.

We later learn that Blackwood disappeared shortly after that, never to be seen or heard from again. His mansion has been held in some manner of trust ever since, but has never actually been lived in during all the years following its original owner’s vanishing act. It appears that the trust has finally run out of money, too, because the dilapidated house has just been sold to rising-star architect Alex Farnham (Guy Pearce, from Ravenous and The Road). Farnham and his new girlfriend, Kim (Disturbing Behavior’s Katie Holmes, whose performance here regrettably recalls her heroic effort to singlehandedly sink Batman Begins)— herself a successful illustrator— mean to renovate the old place from top to bottom. They’ll live on the premises long enough to complete the work, then flip the property and pocket a fortune. And as if the money to be made directly weren’t already a big enough return on Farnham’s investment, the combination of his fame and the mansion’s is such that Architectural Digest owner Charles Jacoby (Alan Dale, from Priest and Star Trek: Nemesis) is talking about running a cover story on the Blackwood house once everything is fully rebuilt and restored. That ought to bolt a couple of JATO bottles to the tail of Alex’s career, right?

There’s one major complication in the offing, however, even leaving aside the weird things that happened in and under the house four generations back. Alex has both an ex-wife and a daughter, the former of whom took the latter to California with her when the marriage came unglued; that was probably about two years ago. Sally (Bailee Madison) has always been a high-strung, needy, emotionally brittle little girl, and she has not adjusted well to the new paradigm. Her mother, meanwhile, is very much into enjoying her newly restored freedom as a single woman, and Sally, quite frankly, is an impediment to the lifestyle that the former Mrs. Farnham wants to lead. Mom has tried to solve the problem by medicating Sally into a stupor, but the kid has finally grown too intractably depressed and anxious even for Adderall. Something obviously has to change, and thus Alex has arranged for Sally to come live with him and Kim for a while. Sally, for her part, is even less happy with that state of affairs than she was with the one pertaining on the opposite coast. Having absorbed and accepted her mother’s preferred explanation for the divorce (Alex rejected wife and daughter alike in favor of his career), she now finds herself confronted with what looks from her child’s-eye view like unanswerable evidence that Mom has now rejected her too. And it only stands to reason that Sally would develop an instant grudge against Kim as a pretender to her mother’s position. About the only upside Sally can see to her new life in Rhode Island is the vast, neglected garden spreading out behind the Blackwood house, with its promise of mysteries to be solved and adventures to be had— and old Mr. Harris the groundskeeper (Jack Thompson, of Man-Thing and Flesh & Blood) does his utmost to deprive her even of that!

Some indication of the motives behind Harris’s interference with Sally’s explorations emerges when she finds the skylight buried in the very densely overgrown region of the garden nearest to the house. Entropy alone cannot account for the skylight’s condition— somebody hid the shit out of this thing. Nor was it all that was hidden. As we learn when Sally reports her discovery to Alex, he and Kim were unaware of the entire basement which the skylight was designed to illuminate. Again Harris tries to obstruct any search for a point of ingress, but it avails him nothing. Nobody’s going to stop a professional architect from locating a walled-over basement entrance once he realizes it’s there to be found. Incidentally, the cellar-concealing modifications were made by Harris’s own grandfather, and although Harris professes ignorance as to the purpose behind them— and, for that matter, behind the impregnable-looking seal on the furnace down there as well— he isn’t a very convincing liar.

Sally, inevitably, is the first to find what Harris and his ancestors had been hiding all these years. While poking around in the newly opened cellar, she thinks she hears voices whispering to her from inside the bolted-up furnace. A naturally imaginative child, she has no difficulty accepting that someone could have been imprisoned within, and she determines to set whomever it might be free. Obviously such work has to be done on the sly, but Sally’s eventual success (Clearly Grandpappy Harris never figured on the invention of WD-40) is rewarded with the emergence of a veritable nation of imaginary friends. The trouble, as you’ve surely surmised, is that the fairies (or maybe gnomes— Sally is forthrightly unclear on the proper taxonomy of the Wee Folk) who begin keeping the lonely and despairing child company from their hiding-places in the walls and ventilation shafts of the old mansion are not nearly as imaginary as Alex and Kim assume, nor are they nearly as friendly as Sally initially takes them to be. The first turning point comes when the tiny creatures steal Alex’s straight razor, and use it to slash every garment in Kim’s closet to ribbons. Alex plausibly blames Sally herself for the vandalism, and the next thing she knows, she’s talking to a psychiatrist (Nicholas Bell, from Dark City and Chameleon) about the house’s reclusive nocturnal tenants. The closet incident may make Sally begin to rethink her relationship with the fairy-gnomes, but she doesn’t truly understand what’s at stake until Harris attempts to reseal the furnace, and is set upon with his own tools by a small army of the creatures. Kim, interestingly enough, is the adult most ready to listen to Sally’s seemingly crazy stories— which start to sound a lot less crazy after the hospitalized Harris sends her to the public library to have a look at Lot 1134 in the Special Collections Room. Lot 1134 turns out to be the private papers of Emerson Blackwood, wherein he described his ordeal at the hands of the things living under his house, and recorded every bit of lore relating to them that he could uncover. The similarities between Blackwood’s “mad” ravings and Sally’s are not lost on Kim, and she comes to believe that something out of the ordinary (even if not necessarily a colony of evil, tooth-stealing fairies) is at work in the mansion. Unfortunately, acting on that belief would obviously mean abandoning the house, and Alex has way too much of his vision for the future tied up in the place to do that without a great deal more persuasion than Kim is capable of bringing to bear at present.

Whatever faults I may find with Guillermo Del Toro’s Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark, I can’t help but love that somebody made a non-parodic horror movie with the Tooth Fairy as the monster. That’s some deliciously twisted shit right there. It also fits neatly into place with the current interpretation of fairy-tale horror and its emphasis on the ancient, shadowed underbellies borne by so many of the cute little stories that we moderns tell to comfort and entertain our children. And perhaps of the greatest significance, the handling of the creatures’ back-story here serves as a vital counterexample to one of the most irritating trends in horror movies today: too much explanatory hand-holding. The TV version’s gremlins never got much in the way of background exposition at all. There were there, they were purposefully if mysteriously evil, and they weren’t fond of bright light; beyond that, we and the Farnhams alike were on our own, and the sheer inexplicability of the situation accounted for much of the movie’s effectiveness. Del Toro and co-writer Matthew Robbins clearly understood that. This Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark may, in keeping with current storytelling tastes, reveal a lot more about the things living under the mansion, but crucially, it doesn’t reveal more than Emerson Blackwood could credibly have observed, researched, and surmised. And just like in the original, the most unsettling mystery of all— just what in the hell is an entryway to the underworld doing at the back of somebody’s fireplace?!— is not even directly acknowledged, let alone resolved. In diametric contrast to, say, Rob Zombie telling us every little thing about how Michael Myers came to be the way he is in his update of Halloween, Del Toro and Robbins have granted us just enough information to outline the sort of danger the fairies pose, and trusted our intelligence and imaginative capacity to take it from there.

Now you’ll notice that I called this movie “Guillermo Del Toro’s Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark,” even though standard movie-critic convention would have it be “Troy Nixey’s Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark” instead. I do so very deliberately. As I suspected, Del Toro’s are the fingerprints most conspicuously in evidence on the remake, and his claim to be considered its auteur is unquestionably the best. Indeed, there is every indication that Nixey and Robbins tried their hardest to minimize their own personal stamps, and to deliver a “Guillermo Del Toro movie” despite Del Toro’s ostensible background position. That— perhaps surprisingly, perhaps not— is where the picture goes somewhat astray. It tries rather too hard to check all the Del Toro boxes, so that the commonalities it shares with the producer’s previous work are too awkwardly obvious. Furthermore, the antecedent from which Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark borrows most heavily is Pan’s Labyrinth, and the inevitable comparisons thereby generated do not favor the present film. It’s too bad, because there surely was much to be gained from building in such echoes. In its basic setup, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark is not merely a riff on Pan’s Labyrinth, but an inversion of it. Here it is the “fantasy” world that is overtly real and destructive, while the mundane hazards of the “real” world are given threatening form primarily by the excessively high pitch to which Sally’s emotions are naturally tuned. Here the juvenile protagonist is put in harm’s way by her true parents, while the hated stepparent ultimately emerges as her most dedicated and effective ally. Maybe what Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark really needed after all was for Del Toro to direct it in person. The recycled themes, situations, and character types might have seemed less forced and self-conscious, and they would surely not have conveyed their current strong impression of Troy Nixey constantly looking over his shoulder to ask, “How was that, Mr. Del Toro? Did I get it right?”

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact