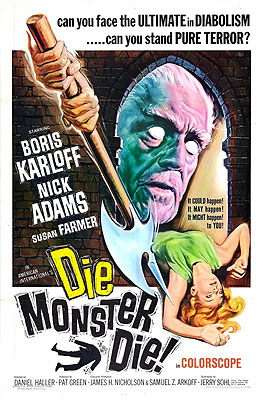

Die, Monster, Die!/Monster of Terror (1965) **

Die, Monster, Die!/Monster of Terror (1965) **

Daniel Haller was the largely unsung hero of American International Pictures’ Edgar Allan Poe cycle during the first half of the 1960’s. Haller served as art director on the great majority of those films (along with the conceptually related The Comedy of Terrors and The Terror), meaning that he was the mastermind behind their unmistakable faux-lavish visual aesthetic, exploiting the necessarily stagebound shooting conditions to create the impression of a claustrophobic little pocket universe where getting buried alive in the family crypt was a perfectly reasonable thing for anyone to worry about. Studio heads Samuel Z. Arkoff and James H. Nicholson were perceptive enough to recognize his importance to the success of the ongoing Poe project, for all that director Roger Corman and star Vincent Price got the lion’s share of the attention in public, and when Corman decided that he wanted to move on from the series after The Tomb of Ligeia, Haller was a natural choice to replace him. But although he did get his first chance to sit in the folding chair in 1965, Haller never did direct any of the post-Corman AIP Poe flicks. Instead, he was given the job of launching a parallel sequence of movies based on the works of H.P. Lovecraft, who in those days was finally being discovered by people who hadn’t read Weird Tales on the regular back in the 20’s and 30’s. Lovecraft’s emerging reputation as something like the Edgar Allan Poe of the 20th century wasn’t the only thing to recommend his writing as the basis for a new cycle of AIP horror films, either. The studio had already made successful use of him, for one of the Corman Poe movies— The Haunted Palace— had actually been a Lovecraft adaptation in disguise. But Die, Monster, Die! (based on “The Colour Out of Space,” one of the better stories from Lovecraft’s drearily predictable and repetitive mature period) failed to grab audiences the way The Fall of the House of Usher and its successors had. As a result, Haller’s Lovecraft “cycle” ended up including just a single other film, made after an extraordinary (for AIP) delay of five years. Nobody should be surprised by that, because Die, Monster, Die! simply isn’t very good, despite duplicating most of the Poe cycle’s appealing look and feel, and despite the still-reliable Boris Karloff stepping in to play the sort of role that would have gone to Vincent Price in the other series.

Die, Monster, Die! begins, like thousands of other horror movies, with a lone man from far away arriving in an isolated community of extremely suspicious, uncooperative people. In this case, the man is an American named Steven Reinhardt (Nick Adams of Frankenstein Conquers the World and Godzilla vs. Monster Zero) and the isolated community is the town of Arkham far out in the English countryside. The fact that Reinhardt is an American probably doesn’t win him any points with the locals (remember, if you’re ever abroad and someone asks you, you’re Canadian), but what really sets them off is the fact that he’s looking for the Witley house. For reasons as yet unexplained, the Witleys have such a bad reputation in town that the taxis won’t go there, the bike shop won’t rent a cycle to someone who wants to go there, and nobody will even give Steven goddamned directions! And of course, nobody is willing to offer any explanation of their prejudice against the Witleys or their house.

So Steven ends up walking. It’s a long trip, and along the way, he sees some awfully strange things. The most ominous of these is the dead patch on the heath. For thousands of feet around a big, ragged pit (which Reinhardt seems not to notice), all of the vegetation is dead— worse than dead, in fact. As he learns when he breaks a twig off of one of the dead trees, all plant-life in the area has somehow been turned to cinders where it stands. Reinhardt’s first impression of the Witley mansion isn’t much more encouraging. In a scene that I swear I’ve seen more times than I could count if I did nothing else all day, Reinhardt is greeted by empty silence, despite the fact that he is clearly being watched by someone that he doesn’t see (in this case, a shadowy woman in a thick, black veil). His knock on the door goes unanswered, but the force of the blows pushes it open, so he walks inside and calls unavailingly to whomever may be within earshot. He noses around through several uninhabited rooms, and finally comes face to face with the master of the house, the aged and crippled Nahum Witley (Karloff), who is predictably less than pleased to see him. But Steven has an ace in the hole, in the form of a written invitation from Witley’s wife (who’ll be played by Freda Jackson, of The Brides of Dracula, when at last we see her), on behalf of their daughter, Susan (Suzan Farmer, from Dracula, Prince of Darkness). Apparently, Susan went to college in America, and she and Reinhardt met in some science course that the two of them took together. Witley clearly intends to throw Steven out anyway, but just then, Susan appears at the top of the stairs, gushing enthusiasm at the younger man’s arrival. Defeated, Witley permits him to stay, but only for a day or two.

We still have one major character left to introduce, so it’s off to Mrs. Witley’s bedroom, to which she has been confined since she came down with a mysterious illness. Surprisingly, Mrs. Witley sends her daughter out of the room, so that she can talk to Steven alone! The old woman (I assume she’s supposed to be old, anyway. By the time we finally see her face, she no longer has one, making it a bit tricky to gauge her age) actually invited Steven to the manor for the express purpose of getting Susan as far away from it as he can contrive to take her! She won’t say why, exactly, but it clearly has something to do with Mrs. Witley’s illness, with the disappearance of the Witleys’ maidservant, Helga, and with the activities of Witley’s insane, dead father, Corbin. Meanwhile, the movie allows us no doubt as to whether Witley is continuing his father’s “blasphemy”— while his wife interviews Steven, he and the butler (Terrence de Marney, from Phantom Ship and Pharaoh's Curse) go down to the cellar, to a room dominated by a structure that is probably supposed to be some sort of Satanic altar (at least that’s what Vincent Price was using it for in The Masque of the Red Death the year before), glowing from within with pulsating green light.

From here on, I’m just going to skim over the plot, if that’s alright with you. This is a very slow-moving movie, and most of the major developments are so deeply buried in the incessant talk that to do otherwise would make this review long enough to be mistaken for a 19th-century Russian philosophical novel. Suffice it to say that crazy Grandpa Corbin built that altar in preparation for a gift of some kind from the “Outer Ones,” and that shortly after his death, the green, glowing thing that now occupies it fell from the sky, creating that crater out on the heath. Because the vegetation around the crater began (at first, anyway) to grow riotously, Witley believed that the thing from above was a blessing from on high that he could use to redeem the family name. The villagers, on the other hand, took its arrival as incontrovertible proof of Corbin’s Satanism, and they took an equally dim view of Witley’s decision to dig the thing up and take it back to his home. But there’s really nothing supernatural going on at all, as any B-movie veteran will know the instant Steven and Susan sneak into Witley’s locked greenhouse to look for the source of the pale glow that Steven saw coming from inside it on the night that he also saw Witley sneaking around in the garden, burying the butler (who had died that evening under highly suspicious circumstances). All of the plants in Witley’s greenhouse are two or three times normal size— tomatoes the size of human heads and such— and the potting shed at the far end of the greenhouse houses a cage full of animals so deformed as to make it hard to figure out what species they might once have been. We all know what it means when huge vegetables, mutant animals, and mysterious glows occur together— radiation! So it comes as no surprise when Steven finds that every plant in the greenhouse has a little shard of what looks like green kryptonite buried in the soil nearby. The final piece of the puzzle— the dead butler, the vanished maid, and Mrs. Witley all used to work in this greenhouse. Could that have something to do with why Mrs. Witley stays hidden behind the canopy of her bed all day? And do you think that veiled woman we keep seeing on the periphery of scenes in this movie could be Helga? Finally, do you think the final act of this movie will somehow involve Steven and Susan trying to fight off mutant versions of the girl’s parents? Hmmm… I wonder…

H.P. Lovecraft has always given filmmakers a hard time. The author’s favorite subject— beings so threatening to consensus reality that seeing them will drive a sane person mad, and just learning of their existence is apt to cripple one’s will to live— is obviously at odds with the requirements of a visual medium like cinema, but even his more manageable recurring themes present obstacles that might not be immediately apparent. The Dunsanian fantasy stories that he favored before Cthulhu hijacked his brain would be prohibitively expensive to film in proportion to their slender plots, his miscegenation parables are a little too obviously what they are to pass muster in the less exuberantly racist country that the United States was trying to become after World War II, and a fair proportion of his most readily adaptable work didn’t see mass-market publication in the first place until decades after his death. It’s telling that the best Lovecraft movie, Stuart Gordon’s wickedly brilliant and transgressively hilarious Re-Animator, was based on a wildly uncharacteristic story from the very beginning of his professional career, to which it bears not much more than a passing resemblance anyway.

Die, Monster, Die! is in no sense an exception to the general pattern of disappointing Lovecraft adaptations. Its crucial weakness (apart from the lackadaisical pace and the calamitous decision to cast a human oatmeal like Nick Adams in the central part) is exactly what Arkoff and Nicholson presumed would be its main selling point— it bears way too much resemblance to one of the lesser Corman Poe movies. It even ends with the house burning down! What Poe and Lovecraft had in common had little to do with their writing styles or subject matter, and everything to do with the transformative influence that they each had on subsequent horror fiction. Poe brought morbid psychology front and center, even in tales that drew most of their plots from the standard gothic repertoire; Lovecraft, for his part, tried to make the reader share in his own mounting unease at how scientific advancement and social change were combining to sweep away the complacency of the 19th century. Those aren’t the same things at all, no matter how large the theme of madness looms in both writers’ works. So by making a Lovecraft movie that comports itself like a Poe movie, Haller essentially rendered the author whom he was supposed to be adapting invisible. The only recognizably Lovecraftian element in Die, Monster, Die! is the business about Grandpa Corbin’s dealings with the Outer Ones, which in practice is nothing more than set dressing. What we’re left with, then, is an uncomfortable amalgam of 1950’s atomic mutant clichés and exactly the kind of gothic commonplaces which Lovecraft avoided throughout most of his career. About the one unqualifiedly positive thing that I can find to say about Die, Monster, Die! is that Boris Karloff at least emerges from it with most of his dignity intact.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact