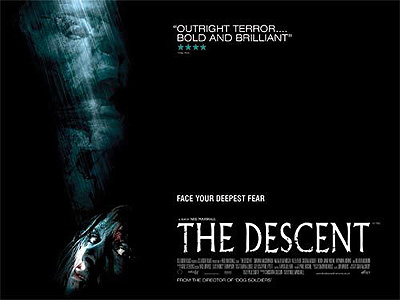

The Descent (2005/2006) ****

The Descent (2005/2006) ****

Despite 20 years of booming business in between, the British horror film just barely existed before the mid-1950’s, and it went back to just barely existing after the middle of the 1970’s. It is especially noteworthy, then, that two of the best— and best-received— horror movies of the past half-decade originated in the UK. First, 28 Days Later… almost singlehandedly resurrected the zombie film, which had rested more or less peacefully in its tomb since about 1993. And now comes The Descent, a movie that is not only exceptionally good, but refreshingly resistant to narrow subgenre pigeonholing as well. It’s enough to give one hope for a British horror renaissance in the years to come.

Sarah (Shauna MacDonald) and her family are on their way home from a whitewater rafting trip with four of Sarah’s friends when disaster strikes. Her husband, Paul (Oliver Milburn), becomes distracted during the drive, and drifts into the opposing lane just in time to slam head-on into an oncoming light truck. The other vehicle is loaded down with heavy wooden dowels at the time of the collision, and though Sarah herself escapes with only minor injuries, Paul and their little daughter, Jessica (Molly Kayll), are both impaled and killed by sharp-ended poles flung from the truck’s cargo bed. Sarah’s circle of female adventurers sort of comes unraveled in the aftermath. Juno (Natalie Mendoza), the one who had been closest to Paul, goes so far as to leave the country, emigrating to the United States. The others— Rebecca (Saskia Mulder), Sam (MyAnna Buring), and Beth (Arachnid’s Alex Reid)— drift apart in ways that are not so attention-getting, but hardly less significant. Rebecca pursues the adventure-vacation agency she and Juno had originally planned to start together, Sam devotes herself completely to earning her medical doctorate, and only Beth really keeps up contact with the bereaved and slightly unbalanced Sarah.

A year later, Juno (ironically enough) takes it upon herself to renew the old ties. Her strategy for doing so is to persuade everybody to fly over to America for a wilderness adventure just like the ones they used to share on a regular basis before Sarah’s tragedy. After spending a night in an Appalachian cabin, reminiscing about the past and bringing each other up to speed on the events of the last twelve months, the women will proceed deeper into the woods to explore Borham Cave. The group dynamic will perforce be somewhat different this time, however, because in addition to Sarah, Sam, Beth, and Rebecca, Juno has invited her new young friend, Holly (Nora-Jane Noone), along for the trip. Beth will describe Holly as Juno’s “protégé” while she and Sarah are driving out to the cabin together, but I don’t think I’m hallucinating when I detect a hint of a sexual vibe between Juno and the girl. But whatever their true relationship, it’s plain enough that Juno is hoping Holly’s aggressive daredevil attitude will rub off on the others— and on Sarah especially.

The spelunking expedition gets off to a good start. By the time the reunited friends have retired to bed at the cabin, there is little indication that most of them have seen almost nothing of one another for a whole year. Better still, Holly’s fears that Borham Cave is now too thoroughly tamed to provide any real excitement (“Boring Cave,” she’d been calling it) prove totally unfounded. Indeed, to look at it, you’d swear no human had set foot inside since Pre-Columbian times. It doesn’t take long, though, for matters to take a serious turn for the worse. The cave is composed of several large chambers connected by passages so narrow that a fully grown human— even a tiny one like Holly— can negotiate them only by wriggling through on her belly. Sarah, the last of the women to attempt a particularly tight tunnel, actually gets herself stuck, and her and Rebecca’s efforts to free her trigger a rock fall that seals off the route back to the entrance. A significant amount of the cavers’ gear winds up on the wrong side of the blockage, too. Worse still, it now comes out that Sarah and her friends actually aren’t in Borham Cave at all! That was the destination Juno gave to both her companions and the relevant local authorities, but their cavern is really one that Juno herself only recently discovered; officially speaking, it may as well not even exist, and anyone who comes to rescue the trapped spelunkers will be looking in the wrong place. The motivation behind Juno’s subterfuge was to secure glory for herself and her friends by being the first to explore, describe, and map an unknown cave system, an experience which she figured would serve as the perfect capper to the meticulously planned reunion. Obviously, the scheme has now backfired almost as completely as could be imagined. But even now, the gods of the catastrophic fuck-up are not finished with our heroines. There’s something alive down in the cave with them, something that could kill them all a hell of a lot faster than hunger, thirst, or suffocation.

The Descent could almost be used as a textbook on how to employ the tropes of the modern horror film without allowing them to devolve into the annoying cliches that have so bedeviled fans during the past couple of decades. For instance, although it’s true that much of the plot advancement is driven by really stupid behavior on the protagonists’ parts, all of the women’s various boneheaded decisions are always perfectly within character. They also have vastly more serious consequences— especially for the people actually making the mistakes— than one generally sees in a horror movie these days. The Descent is equally impressive for its astute employment of the “monsters hiding half-seen in tight, dark spaces” gambit, a scare technique driven so far into the ground by a thousand lousy Alien clones that it sometimes seems like it could never be made to work again. For one thing, the monsters themselves are great, their design a canny compromise between visual impact and biological plausibility that puts them in the same class as Creature from the Black Lagoon’s gill-man. And for another, director Neil Marshall makes excellent use of unusual and underperforming light sources to maximize the menace projected by the creatures and their lair. My favorite example is Holly’s digital camcorder, the infrared setting of which provides the women with their clearest picture of their surroundings— but with a greatly restricted field of vision that makes the cave seem even more threatening than it does in total darkness.

I do have a few small complaints, however. First, I’m not crazy about the ending— about either ending, as a matter of fact. Although I certainly appreciate the 70’s-style bleakness of the original conclusion, the way it plays out in detail strikes me as just a little bit awkward. The truncated ending shown in American theaters, meanwhile, is downright stupid, turning what was supposed to be the setup to a horrid revelation into a cheap, tawdry shock that makes absolutely no sense. Second, I found it extremely difficult to tell the characters apart— not in the sense that their personalities were insufficiently distinct, mind you, but in the sense that I could not physically distinguish them with any reliability until the cast had been whittled down to a single blonde and a single brunette. Part of the problem was a seemingly unavoidable side effect of the otherwise very smart decision to keep the cavern interiors as dark as possible, but the rest of it stems from the egregious overuse of Shakycam during the second half of the film. Finally and most importantly, the monsters are just too damn easy to kill when they fail to take their prey by surprise. Or alternately, one might say that the women are much too tough. However you want to put it, the problem can be seen most clearly during the sequence in which Juno emerges victorious from a close-quarters grapple with three of the things simultaneously. After the first attack, the blocked-off path to the surface always seems like a bigger threat than the creatures, which is exactly opposite to the way things ought to be. These are all fairly minor quibbles, however. The Descent is a truly exceptional movie, and I hope there are a lot more where it came from.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact