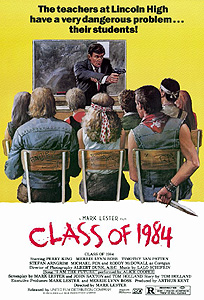

Class of 1984 (1982) ***½

Class of 1984 (1982) ***½

I don’t know a single self-identified punk rocker who has seen Class of 1984 and doesn’t love it. That might seem strange to some of you, seeing as the portrayal of the punks in this movie could best be described as mendaciously caricatured demonization. After all, demonizing people mendaciously is not generally a very effective strategy for winning their affections. Let me tell you a little open secret, though: the truth is, we punks kind of like how we always end up being the bad guys on those rare occasions when popular culture at large deigns to take notice of us at all. In a warped way, it’s flattering to be seen as a menace to society when your main operative theory has it that all the generally accepted ways of doing things— socially, culturally, politically, economically— are fucked up at the core. For those who make a philosophical point of rejecting the mainstream, it’s a sign that they’re doing something right when the mainstream rejects them right back. Furthermore, the punksploitation movies of the late 70’s and early 80’s have only become more appealing from that perspective since the broader consumer culture finally succeeded in co-opting and domesticating punk rock during the 1990’s. In this era of Green Day and Hot Topic, it’s heartening to watch something like Class of 1984 and be able to say, “Remember back when people used to be scared of us? Man, weren’t those the days?”

As the movie opens, it’s the start of a new semester at Abraham Lincoln High School. It’s also the start of a new phase in the career of music teacher Andrew Norris (Perry King, from Mandingo and The Possession of Joel Delaney), who has come to Lincoln High to replace the school’s recently departed music instructor after a long hiatus from the education business in a small town far away. Lincoln is not like any other school where Norris has worked. There are metal detectors at all the entryways, armed security guards patrol the corridors in support of the usual faculty hall monitors, and Principal Morganthau (David Gardner, of Prom Night and Hollywood Hot Tubs) seems to spend most of his days observing the activity around the campus over a panoptic network of closed-circuit television cameras. And even with all those precautions, there’s still graffiti all over every square inch of everything, the bathrooms are still bustling drug bazaars, and random violence is still so rampant that biology teacher Terry Corrigan (Roddy McDowall, from Laserblast and The Black Hole) feels compelled to carry a pistol in his briefcase. The really astonishing thing, though, is that a drastically disproportionate share of the institution’s woes are the work of just five students. The ringleader of these high school hooligans is named Peter Stegman (Timothy Van Patten, of Zone Troopers and Curse IV: The Ultimate Sacrifice); his cronies are Patsy (Lisa Langlois, from Happy Birthday to Me and Phobia), Fallon (Neil Clifford, from Skullduggery and Easy Prey), Barnyard (Keith Knight, of Whispers and My Bloody Valentine), and Drugstore (Stefan Arngrim, of Strange Days and Fear No Evil). Stegman controls the Lincoln High drug trade. He’s behind the teen prostitution ring that operates out of the local punk club. He runs an extortion racket dedicated to separating his school’s nerds, geeks, and dorks from their pocket money. And it happens that he’s now one of Norris’s pupils. Suffice it to say that the new teacher is not prepared to deal with this situation.

He certainly tries, though— in marked contrast to Terry Corrigan and the other instructors— and that’s where his real troubles start. Bridling at the challenge Norris represents to his mastery of Abraham Lincoln High, Stegman has Patsy (whose specialties apparently included break-ins and burglary in addition to polymorphous sexual depravity) sneak into the main office and snag a copy of the faculty directory. Now armed with the address where Norris and his wife (Merrie Lynn Ross, from Schoolgirls in Chains and The Lucifer Complex) live, Stegman and his gang are in a position to mount a terror campaign against the bothersome new teacher right on his home turf. They start small, with a drive-by squirtgun shooting, but that minor incident provides a hint, for those who care to see it, of what Norris can expect in the future should he continue to lock horns with Stegman.

Meanwhile, Norris sinks as much of his energy as his classroom nemesis will allow into doing what the Board of Education pays him for— which is itself a novel turn of events at Lincoln High. Specifically, he attempts to forge his most adept students into a regular high school orchestra, with arch-nerds Arthur (Michael J. Fox, of The Frighteners and Mars Attacks!) and Deneen (Erin Flannery, from The Incubus and Uninvited) at its center. Norris’s two ongoing projects intersect when one of Arthur’s friends gets it into his head to try PCP, and has a fatal freak-out right there at school. The teacher is unable to prove that it was Stegman who sold the dead boy his drugs, but Norris was not born yesterday, despite all the flack he takes from his colleagues and superiors for his “naïve” idealism. Stegman, for his part, is more concerned about Arthur, the one witness to the sale apart from his own minions, and he does everything within his considerable power to terrify the other boy into silence. Norris picks up on that, too, and steps in to put a stop to it— even when that means taking on the gang off of school property. From that point forward, Class of 1984 starts looking less like a 1980’s remake of The Blackboard Jungle and more like Cape Fear High School. And while Stegman may not have the physical presence of Max Cady (in either incarnation), he has both a pack of followers every bit as sociopathic as he is and that combination of nihilism and masochism so often ascribed to punks in those days to make up for what he lacks in brute strength.

While we’re on the subject of people ascribing things to punk rockers, another factor accounting for Class of 1984’s persistent popularity among the very people it condemns is the unusual amount of stuff it gets at least superficially right, even if that stuff takes an overblown and distorted form, or if writer/director Mark Lester and his co-scripters, John Saxton and Tom Holland, don’t necessarily grasp its significance. Lester and company’s punks eschew hippy drugs like marijuana and LSD in favor of heroin and cocaine. Where possible, they try to exploit the system’s weaknesses to give themselves freedom of action beneath and beyond the notice of the powers that be, rather than confronting authority directly. Their destructive impulses are as likely to be directed toward themselves and each other as toward the “outside” world, and their more overt clashes with representatives of official power are apt to land them in more trouble than they’re actually equipped to handle. The aforementioned nihilism and masochism are portrayed defensibly, if also without much sign that the filmmakers understood that there were reasons behind those aspects of early punk culture. And although this is really a small thing overall, Class of 1984 earns distinction as one of the few punksploitation movies I’ve seen in which the costumes and makeup on the actors playing the major punk characters are genuinely of a piece with those of the real-life punks who responded to the casting call for extras, even when scrutinized with a practiced eye. Finally, Mark Lester made a truly startling bid for authenticity during the concert scene early on by filming it at one of Toronto’s foremost punk clubs, and hiring Teenage Head (unjustly overlooked luminaries from the first flowering of punk rock in Canada) to provide the music. (Teenage Head’s presence in the film really makes one wonder why Alice Cooper, of all people, got the job of supplying the main title theme. The Damned, for example, would have been perfectly capable of delivering a song as lame as Cooper’s “I Am the Future” in 1982.)

Of course, an accurate reflection of early 80’s punk culture was at best a secondary concern for Lester, who essentially saw the punks of his day as spiritual successors to the similarly fretted-over juvenile delinquents of the 1950’s, and who intended Class of 1984 as a modern counterpart to the earlier era’s youth violence panic-pieces. Thus the credulity-straining portrayal of Peter Stegman as a teenage crime lord in the vein of John Ashley’s character in High School Caesar, complete with a waiting list of small-time hoodlums who aspire to work for him. (One difference between the 50’s and the 80’s can be discerned from the fact that Class of 1984 depicts a rather more plausible slate of criminal activities for Stegman’s operation, even if that operation’s existence in the first place is as implausible as ever.) An interesting side-effect of the JD godfather premise is that it defeats any temptation there might have been to make Stegman just a dumb thug like, say, the punks in those infamous episodes of “CHiPS” and “Quincy.” Rather, it is necessary for Stegman to be a smart— even gifted— thug, which introduces yet another unexpected bit of authenticity. Punks, after all, traditionally start off as just plain misfits and outcasts before finding their way to a counterculture that embraces and extols the inability to fit in, and exceptional intelligence is at least as likely to make one an adolescent outcast as exceptional stupidity. In my two decades of involvement in the Maryland and Washington DC punk scenes, I’ve known far more bright kids unwilling or unable to conform to their elders’ expectations than I have violent, resentful morons. Timothy Van Patten does fine work with the part, occasionally even managing to be halfway believable as an underage boy. I share Lester’s amazement that Van Patten’s career didn’t take off on the strength of his performance here.

Lester’s second major aim with Class of 1984 was to put a new spin on the vigilante films that were so prevalent in the early 80’s, and he was just as successful there as he was in updating the old JD movies. The key to that success lies in the unlikelihood of Perry King and Roddy McDowall as vigilantes. Lester was right on the money in predicting that the picture’s most memorable scene would be the one in which Corrigan pulls out his pistol in class in a crazed attempt to terrorize his terroristic students into finally learning something. As striking as it is when Stegman roughs himself up in the boys’ room so as to frame Norris for assaulting him, that bit has nothing on the image of Patsy struggling to remember how many chambers there are in the human heart while Corrigan holds a gun to her face. For the most part, however, the fight against the punks is Norris’s, and that teacher’s progression into vigilante violence follows a markedly different pattern from what one sees in most contemporary films about self-appointed crime-busters. The central point is that Norris does not simply want to be left alone by the criminals around him so that he can carry on his business in peace. Reigning in Stegman and his minions and making productive citizens out of them is his business, and so the conflict between the two sides is inherently unavoidable even though Norris starts off by disavowing the adversarial model that his colleagues consider normal in relations between Lincoln High teachers and their students. Class of 1984 thus has a tragic aspect that is absent from most vigilante movies. One could just as easily build a feel-good Oscar-baiter around the pairing of Stegman and Norris, a sort of punk rock Stand and Deliver, but instead, Stegman and his gang end up dragging Norris down to their level. Whether or not Lester consciously realized this (and his comments on the film over the years rather suggest that he did not), he and his collaborators have created one of those rare and thought-provoking movies in which nobody really wins— something far more interesting and meritorious than the crass vendetta flick for which Class of 1984 might be mistaken at a distance.

This review is part of the B-Masters Cabal’s month-long look at counterculture exploitation movies. Click the link below to see how my colleagues are faring in their encounters with the various restive youth tribes.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact