Castaway (1986) ***

Castaway (1986) ***

One day in 1980, a dissatisfied Inland Revenue clerk (Inland Revenue being the British counterpart to the IRS) named Lucy Irvine came upon a very strange advertisement in the classified section of the travel and lifestyle magazine, Time Out: “Writer seeks ‘wife’ for year on tropical island.” The ad was placed by Gerald W. Kingsland— memoirist, journalist, ex-soldier, adventurer, and all-around retrograde macho man— and yes, he was completely serious. Indeed, he was so serious that this was his third attempt to play desert island castaway. The previous two times, first on Cocos Island in the mid-Pacific, then again on the aptly named Robinson Crusoe Island off the coast of Chile, had failed largely due to unsuitable locations. By the 1970’s, Homo sapiens had spread to just about every spot on the globe that could be inhabited long-term, making it very difficult to find a genuinely deserted island that could still support human life; Cocos and Robinson Crusoe, remote as they were, both saw too much traffic from the outside world to give Kingsland the experience he craved. Irvine answered the ad, and Kingsland selected her from a small pool of competitors to be his companion in primitivism. The venture went considerably better than anyone could reasonably have expected— which is to say that Lucy decided she detested Gerald before they even set foot on Tuin Island, that the pair spent the entire year on the knife-edge of starvation and dehydration, and that they suffered constantly from tropical infections and the effects of toxins produced by the corals that surrounded their retreat, but that they both did live to tell the tale. In fact, their tale was told three times: first in Irvine’s memoir, Castaway; again in Kingsland’s memoir, The Islander; and finally in Nicholas Roeg’s film named for the former book, but apparently incorporating material from both.

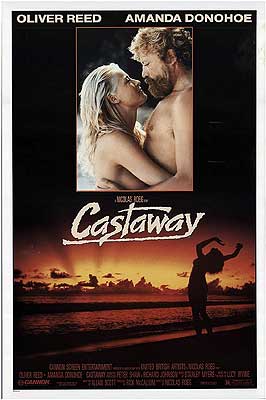

We begin with a part of the story that Irvine’s version understandably elides. Gerald Kingsland (Oliver Reed, of Fanny Hill and The Shuttered Room), smarting from a failed marriage, fed up with the burden of parenting two teenaged boys in a broken household, and horrified by what he sees (halfway defensibly in those days) as the looming collapse of British civilization, commits to a truly drastic change of circumstances. He vows to find himself an uninhabited tropical island, and to live on it for a year with no company apart from one suitably appealing woman. He sells off whatever he owns that’s worth anything, and squirrels the money away to pay for transport (obviously he won’t be going anyplace served by a major airport) and provisions. He does exhaustive research into potential venues for his year of roughing it, looking for that perfect combination of mild climate, dependable local sources of food and fresh water, and freedom from regular human habitation. And as we already know, he puts out a call for a female co-castaway with an ad in Time Out. His ad catches the eye of Lucy Irvine (Amanda Donohoe, from The Lair of the White Worm and Starship Troopers 3: Marauder), an entry-level civil servant about 20 years Gerald’s junior, who shares some of his jaundiced outlook on their society’s immediate future.

Lucy knows the idea is crazy, but it strongly appeals to her anyway. Restless yet directionless, and frankly a little bit overwhelmed by the realities of adulthood, she finds it very hard to resist the temptation of an excuse to blow off everybody’s expectations of her for an entire year, in a place where it won’t matter a bit that she never quite figured out what she wanted to be when she grew up. Still, she can’t bring herself to tell even her roommate (Sorel Johnson) what she’s thinking of doing. In fact, Lucy tries pretty hard to prevent Laura from so much as learning of Gerald’s existence while they conduct their weird quasi-courtship in the weeks following first contact. Eventually, though, Lucy makes up her mind to sign on with Gerald on his mad scheme, and lets the story get out at last. In fact, she lets the story out far enough to secure a book deal for a memoir of the project, and her advance from the publisher (Kingsland naturally has one of those, too) pays her way to Brisbane, Australia, which Gerald has selected as their forward base of operations for picking out the best of the many small islands in the Torres Strait.

It’s in Brisbane that an unforeseen complication arises. Astonishingly, the Australian government objects to Project Castaway on grounds of sexual morality, and refuses to issue the necessary long-term visas unless Gerald and Lucy marry for real. Fighting that outmoded official prudery consumes most of the remaining money from the couple’s respective would-be publishers, and still ends in failure. The unexpected snag also has a cripplingly destructive effect on the couple’s relationship. Quite simply, Lucy is ornery. Tell her that she has to do something she wanted to do, and suddenly she doesn’t want to do it anymore. It was one thing to become Gerald’s “wife” for the duration of their South Seas adventure, but now that she’s forced into a marriage without the ironic quotation marks, she notices all at once that she actually doesn’t like Gerald very much. Overnight, Lucy cuts off all sexual relations, and casts a sharply critical new eye on everything he does. Not without justification, Gerald feels as though he’s been given the bait and switch, but he and Lucy agree wholeheartedly that they’ve come much too far and sacrificed far too much to turn back now. They’re going to Tuin Island together whether they can stand the sight of each other or not!

The rest of the movie focuses on how the pressures of survival, in what turns out to be a much more hostile environment then either Gerald or Lucy anticipated, gradually force them back together. Roeg tells the tale in a most curious way, however. Castaway has some of the features of a conventional romance story— for instance, the strife that enfolds the former lovers at the beginning of their adventure would be classic bodice-ripper material if Lucy ever wore any bodices, and there’s a feint in the direction of a love triangle when two studly Aussie sportsmen (Tony Richards and Todd Rippon, the latter of The Frighteners and Hercules and the Lost Kingdom) arrive bearing, of all things, census forms from the government— but the fact that the protagonists are slowly starving to death the whole time subtly transforms the movie into something else entirely. Similarly, Castaway has the appearance of a glossy sexploitation movie, but isn’t one of those, either, in any ordinary sense. Sure, the setting and the way it’s used recall the likes of Taboo Island or the more nature-loving Emmanuelle cash-ins, and Amanda Donohoe is nude pretty much constantly from the moment Lucy sets foot on Tuin. It would be an awfully weird softcore skin-flick, though, that was explicitly about people not having sex, and that’s exactly the central dramatic issue so far as the protagonists’ relationship is concerned. You might say that Castaway is set up to give audiences an experience analogous to Kingsland’s. It teases with the prospect of a hedonic Eden, where sensuality is free to run amok, but delivers instead a reality defined by infected hornet stings, an increasingly foul water supply, and inescapable acrimony.

Believe it or not, Castaway was released by the Cannon Group. The same Cannon Group, in case it’s not clear, that was responsible for Ninja Hunt, Cobra, and Masters of the Universe. That’s the thing about being the number-one independent studio in Hollywood, though— you can afford to take chances here and there, and the occasional wildly uncommercial project can burnish your critical reputation. I can almost hear Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus talking themselves into giving Castaway the go-ahead: “That was Nick Roeg on the phone. He wants to make this arty character-study thing about how people change when there are no more rules or social expectations, but they know they need each other to stay alive. Yeah, I know— not really our thing. It’s based on some broad’s memoir, though, so we can push the ‘true story’ angle. And it’ll have a ton of skin in it, so we can sell it on sex, too. And it’s set on an island, so it’ll be like having our own Blue Lagoon.” When you put it like that, maybe Castaway isn’t so uncommercial after all.

Still, this is one of those cases where your expectations going in will matter a great deal. I remember being more confused than anything else when I saw Castaway on “Showtime After Hours” in the late 1980’s. For all practical purposes, that was Showtime’s Eurosmut program, and as I said before, Castaway merely looks like Eurosmut. I was unprepared for a film that dealt seriously with the psychology of a massively dysfunctional couple in a situation where they couldn’t afford to let their dysfunction get the better of them, nor was I prepared for one that was so unstinting about spraying concentrated buzzkill all over the fantasy at the core of its premise. However, if you go in knowing that Castaway has little interest in beautiful people (or at any rate, one beautiful person and another who used to be beautiful about 20 years and 20,000 shots of whiskey ago) fucking under the tropical sun— that it is in fact a critique of the kind of thinking that causes movies like that to be made— then I think you’ll be very satisfied with what it delivers instead. The script is smartly if elliptically adapted from Irvine’s memoir, and Roeg displays a canny knack for juxtaposing the gorgeous setting against the substantially less gorgeous relationship unfolding within it. Roeg is also remarkably deft, in the pre-Tuin first act, about implying Gerald’s and Lucy’s reasons for wanting to chuck it all and go live on an island somewhere without ever overtly addressing any of them.

Oliver Reed and Amanda Dononoe, meanwhile, are both amazing, the latter not least because this was her first major film role. Kingsland, unsurprisingly, looks significantly crazier in Reed’s hands than he did in Irvine’s (hers was the only Tuin Island memoir I could obtain before my self-imposed deadline for this review), but in a way that makes perfect sense under the circumstances. In Irvine’s book, we see Kingsland through the eyes of someone even more committed to the concept of “the Island Year” than he is, which tends to suggest that Irvine at the time was maybe a little mad herself. And when you consider how far from Gerald’s imaginings the experience of his year on Tuin turned out to be, with no opening left for restarts or do-overs, it’s only to be expected that he’d go a little batty. No English actor of his generation did batty quite like Oliver Reed. Donohoe, for her part, has a complicated balance to strike. There’s every indication that Lucy’s relationship with Gerald would have continued to the end of the year on a mutually satisfying path if only the Australian immigration authorities hadn’t stuck their noses into it. It would be easy, then, for her to look like the villain, since she’s the one fucking up a good thing for reasons that have nothing to do with the couple themselves. But Lucy had her own vision of the Island Year, one which Gerald fucks up first with his complacent attitude toward building up a material culture on Tuin, and later by establishing commercial ties with neighboring Badu Island. Her Gilligan’s Island fantasy is arguably even more unreasonable than his Adam and Eve fantasy, but Donohoe makes clear that it means just as much to her, and maybe even more. Her performance is the key to making Castaway a narrowly averted tragedy about two people’s neurotic dream-worlds colliding under potentially deadly conditions, rather than a hateful screed about how bitches be crazy.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact