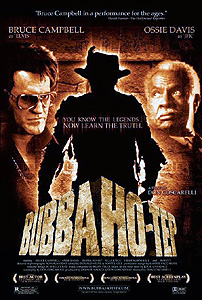

Bubba Ho-Tep (2003) ***½

Bubba Ho-Tep (2003) ***½

Bubba Ho-Tep. The title alone makes you want to rush right out and see it. But as I’ve said before, such arresting titles frequently come attached to movies that are nowhere near worthy of them. Luckily, this is not one of those cases. Instead, Bubba Ho-Tep is the best mummy movie I’ve seen in years, probably the best to hit the screen since 1959. Director Don Coscarelli does a superb job keeping his grip on a story that could easily have gone spiraling out of control, and star Bruce Campbell displays a degree of acting talent that I never suspected he had in him.

On the outskirts of the small, East Texas hamlet of Mud Creek lies the Shady Rest retirement home. Like all nursing homes, Shady Rest is a rather grim and unsettling place, filled with men and women who seem to have taken their seats in death’s waiting room, only to be forgotten about by the receptionist. Everywhere you look, you are faced with people whom age has sunk so deep into physical or mental disrepair that such family as they have are no longer able to deal with them, or with others who are not so far gone as that, but who have no one to take care of them now that they have become too feeble to take much care of themselves. Among the latter group at Shady Rest is a man you probably think you know a good bit about— one Elvis Aron Presley (Campbell, from The Evil Dead and Maniac Cop). Now I know what you’re thinking: “That’s impossible! Elvis Presley kicked it on the crapper way back in 1977— everybody knows that!” Yeah, well you just think you know about Elvis. It just so happens that the man who checked out in Graceland while (to borrow an uncharacteristically eloquent turn of phrase from the Dead Milkmen) “stoned and fat and wealthy and sitting on the bowl” wasn’t really Elvis at all. It’s like this, see...

Sometime around 1974, the King had himself a little epiphany. Taking stock of his life, he realized that it quite simply wasn’t his anymore. Hell, for that matter, he was barely even Elvis anymore. Little by little, he’d let his true self slip away to be replaced by some cartoonish creation willed into existence by Colonel Parker and the media. Well as it happened, this dawned on Presley right at the same time that a curious cultural phenomenon was rising up that just might offer him a way out of his fix— Elvis impersonation. Elvis spent the next year or so checking out all the impersonators he could find (Parker and the rest of his handlers figured this new obsession was just one more manifestation of the egomania they had so assiduously cultivated in their client), until he discovered a man by the name of Sebastian Haff. Haff was the best of his kind, virtually indistinguishable from the real thing, and in a private meeting outside the hearing of Parker and his cronies, the King offered Haff the following deal. Sebastian would take his impersonation to a higher level, actually taking on Presley’s identity while Elvis himself went into hiding as Haff. The two men signed a contract, which further stipulated that the real Elvis could undo the trade at any time, and when they parted, it was Haff who left in the limo with Colonel Parker. But not much later, that contract was destroyed when Elvis burned Haff’s trailer to the ground in a barbecuing accident. With no way to prove who he really was, Elvis was forced to carry on the ruse even after he wearied of it, and Sebastian died at Graceland while still in character. Elvis soldiered on for a decade or more “impersonating” himself, and came to enjoy it almost as much as he had the early days of his career. But one night— by which point Elvis was definitely no spring chicken— he fell from a stage, broke his hip, and lapsed into a coma. When he woke up some years later, he was an inmate at Shady Rest, crippled and impotent, with a cancerous lesion on the end of his schlong.

Naturally nobody at the nursing home believes Presley’s story, or at least, no one on the staff does. There is one other patient who knows he’s telling the truth, though, and that’s his buddy Jack (Ossie Davis). Jack is an aged black man who contends that he is really John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Jackie saved his brain when it was shot out of his head, or so Jack says, and had it preserved in a secret room in the White House; his empty cranium was then filled up with sand and fitted with a device that would allow his body to respond to his brainwaves, even over great distances. But Lyndon Johnson and the CIA got wise to the fact that their attempt to kill Kennedy had failed, so they dyed him black and packed him off to East Texas, where they could keep an eye on him and prevent him from getting in their way. Small wonder he and Elvis are such good pals, huh?

There are worse things going on at Shady Rest than the neglect and despair typical of nursing homes, however, and not all of the frequent deaths there are properly attributable to sickness or old age. One night, a kleptomaniacal old lady is killed in her room by something that enters it in the guise of a bug as big as a man’s fist (or “as big as a peanut butter and banana sandwich,” in Elvis’s later formulation). This isn’t just any giant arthropod, either; though most of the characters who see it take it for a cockroach, savvier observers will recognize it as a scarab beetle, the insect sacred to the ancient Egyptians. Elvis himself doesn’t make that connection the following night, when the beetle attacks him (and gets ground to a pulp in the fan of his space heater when the King defends himself with surprising vigor), but Presley will learn about the Egyptian angle soon enough. Not long after fighting off his scarab, he drops in on Jack just in time to save him from a fate worse than death. To hear Jack tell it, Elvis’s approach scared off a powerful assailant who had him pinned to the floor and was preparing to suck something out of his asshole. Jack’s belief is that that something was his soul. Why? Well that gets us back to Egypt...

Jack takes Elvis into the nearest men’s room, where there is a strange assortment of pictures scrawled on the wall of one of the stalls. These pictures, Jack explains, are Egyptian hieroglyphics. Jack discovered the inscription last week, and he made a point of translating it a few days later when his daughter took him into town to visit the public library; so far as Jack can determine, it reads, “Cleopatra does the nasty.” While doing this research, Jack fortuitously stumbled upon the information that the ancient Egyptians believed the human soul could be extracted from the body through any of the major orifices— the mouth, the nose, the vagina, the anus. Between the killer scarabs, the hieroglyphic graffito, and the ass-centric attack of the big, shadowy man who pounced on Jack that night, the former president believes that a living mummy has come to Mud Creek, and that it is feeding on the souls of Shady Rest in order to sustain its unnatural existence. If Jack is right, then that raises two questions. Number one, how did a living mummy end up in East Texas in the first place? And number two, what are a couple of dotty old men, both of them confined to a nursing home and neither one of them capable of walking farther than the width of his bedroom without assistance, going to do about it?

The biggest danger with something like Bubba Ho-Tep is the possibility of its creators being unable to see past its screwy premise, and believing that their job is done once that premise has been established. This movie could very easily have wound up being another Rockula. Fortunately, Don Coscarelli has a long history of doing mostly right by eccentric ideas, having created both the Phantasm and Beastmaster series. He brings a seemingly impossible degree of depth and maturity to Bubba Ho-Tep, which ends up being as much a thought-provoking musing on the travails of the abandoned elderly as it is a fantasy about two colorful old geezers saving their retirement home from a soul-sucking mummy. Some viewers might complain about the movie’s rather methodical pace, but I think it makes good sense in context. Nobody would ever describe life in a nursing home— or the people who live it— as fast-moving, after all. Bruce Campbell’s performance, meanwhile, is a revelation. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen an actor juggle pathos and humor so adroitly before, and I never would have expected anything of the sort from a man who has spent the bulk of his career playing a succession of mostly interchangeable sharp-tongued wise-asses. Not only that, at no point did I ever find myself seeing Campbell as anything other than a geriatric Elvis Presley, which is an astonishing accomplishment for an actor who has previously displayed as little range as Campbell has.

Let’s not forget about the funny side, though. Bubba Ho-Tep is one of the wittiest movies I’ve seen recently. Its greatest strength as a comedy comes from its creators’ understanding of a point that is too often lost— that crudity and sophistication can both have their place in the same work, and that the best comedy is often that which keeps its audience off balance by deploying both in unpredictable ways. Bubba Ho-Tep lets you know at the very beginning that it’s going to be that kind of a movie when it follows one pre-credits title card defining the Egyptian term “ho-tep” (incidentally, there’s a third reading that they missed— the phrase literally means “loved by,” so that a pharonic name like Amenhotep claims special divine favor toward its bearer) with another purporting to define “Bubba.” Jack’s presence in the story is used to introduce a series of very erudite running gags on the theme of Kennedy assassination conspiracy theories, and the various “Elvis is alive” kook narratives get a workout, too. But that kind of thing sits side by side— and quite comfortably, at that— with a cowboy boot-wearing mummy who issues curses that the subtitles translate, “Bite the dog-dick of Anubis, ass-wipe!” (complete with “hieroglyphics” depicting a hand hovering below the rear of a squatting stick-figure). It’s not an easy trick to pull off, and a lot of directors wouldn’t even come close, but Buhba Ho-Tep shows just how much Don Coscarelli has grown as a filmmaker since the intriguing but uneven movies that first brought him to the world’s attention.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact