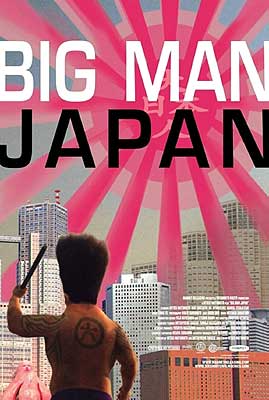

Big Man Japan / Dai Nihonjin (2007) ***

Big Man Japan / Dai Nihonjin (2007) ***

Usually nothing stops comedy deader in its tracks than not getting the joke. That said, I have found that once in a while, a joke can still work on some other level if I almost get it. I’m not sure I can explain that, but I can offer an example in the form of Big Man Japan, the debut feature of Japanese TV comic Hitoshi Matsumoto*. This movie is an extremely strange and wildly inventive satire, but it’s so purely and thoroughly Japanese in its concerns and outlook that Western viewers will likely struggle to keep track of everything it’s satirizing. The obvious targets include monster movies and tokusatsu TV shows like “Ultraman” and “Kamen Rider,” 21st-century reality television, and the attitudes of the Japanese public to all of the above. But it seems like there’s a lot of other stuff in here that’s more difficult for outsiders to tease out. Something about the incursion into Japanese culture of American-style consumerism in its crassest form. Something about the state of the Japanese family in the aftermath of the Lost Decade. Something, I think, about the dysfunctional relationships that Japanese men have with their careers. Maybe even something about the declining relevance of traditional Japanese cultural forms like sumo wrestling and kabuki theater, or about the country being nudged toward remilitarization by the very enemies-turned-allies who imposed demilitarization on Japan in the first place. Honestly, I’m amazed that Big Man Japan got any official release overseas at all, let alone releases in three different European languages! But because the film’s main comedic register is absurdism, the obscurity of its meaning tends to reinforce that, so that the parts I don’t quite understand retain their humor by association with the parts that I do.

An unseen cameraman-narrator-interviewer (his voice belongs to Tomoji Hasegawa) is following around a 30-something sadsack named Masuro Daisato (Matsumoto himself, whose other turns in front of a movie camera include Symbol and R100), observing his routine and asking him questions about his life. Daisato leads a dreary existence, dwelling in a cramped and cluttered bachelor pad of a cottage somewhere in Tokyo, never varying his order at the ramen restaurant where he has lunch several times each week, and doing little for entertainment beyond going to the movies and haunting the park where he used to take his daughter (Kaho Okajima) to play when she was very little. He and his wife (Shion Machida, from Dragonhead and Inugami) are separated, he sees his daughter so infrequently that he’s no longer certain of her age (eight, maybe?), and there’s no indication that he has any friends whatsoever in the usual sense. Daisato’s job— which doesn’t pay nearly well enough to suit him— keeps him on call at all hours of every day and night, although the amount of time that he spends actually doing it is so small that boredom is a major challenge. He has more ostensibly free time than he knows what to do with, but no way of planning how to use more than a couple hours of it at a time— and vacations are absolutely out of the question! It isn’t at all clear at first, though, why the guy with the camera reckons Daisato worthy of such attention. Even if the idea were merely to document the patterns of urban unhappiness in contemporary Japan, why this poor schmuck in particular, rather than any of the others like him who must surely be leading their own lives of quiet desperation a few blocks up or down the street?

The first intelligible clue to that mystery is the sign above Daisato’s front door identifying his home as property of the Department of Monster Prevention, but the solution comes all the way to light only when his phone rings with a summons to the Kanto Number Two Electric Transformation Plant. Tokyo is under attack by a Strangling Monster, and it is Daisato’s duty to stop it by assuming his titanic alter ego as Big Man Japan! For six generations, the men of Daisato’s family have had this gig, turning themselves into cudgel-wielding giants to defend the nation against threats too weird for conventional military forces to handle. Back in the Showa era, when monsters were more common, there were many such families— enough that the Department of Monster Prevention had to maintain 52 electric transformation plants to manage them all. The monster-fighters were treated as national heroes and celebrities of the highest rank; Daisato claims that his grandfather, the fourth Big Man Japan (Taichi Yazaki), never had to carry a wallet, so eager were people to show their appreciation. Today, however, with the frequency and intensity of monster attacks on the wane, one huge guy with a proportionately immense truncheon is deemed sufficient to handle the problem, and the public doesn’t pay much attention to Daisato or his battles on their behalf. Whereas his father (played in flashbacks by Ronin District’s Motohiro Toriki) and grandfather had their clashes with kaiju not merely filmed and broadcast, but presented as prime-time television or shown as newsreels accompanying prestigious motion pictures, Masuro has been shunted into a fifteen-minute timeslot at 2:40 in the morning, between the Home Shopping Club and the small-hours weather update. What’s more, many people have grown overtly hostile to the Department of Monster Prevention and its work, objecting to both the property damage that inevitably results when Daisato squares off against a monster and the disruptions to local electrical service attendant upon his transformations. At best, the sixth Big Man Japan is treated as a boring anachronism by the people whom he defends, and at worst as a nuisance coequal to the occasional marauding kaiju.

For the rest of the film, Big Man Japan toggles back and forth between examining Daisato’s increasingly dismal day-to-day existence, and showing him in action against a succession of indescribably weird and somehow pitiable monsters. We watch the ruins of his family slide irrevocably into estrangement, learn of Daisato’s troubled relationship with his overly ambitious dad, and witness his devotion to his now senile grandpa, who was forced to take on a second tour of duty late in middle age after the fifth Big Man Japan accidentally electrocuted himself to death in an attempt to grow even bigger. We observe Daisato’s sad, parasocial quasi-friendship with the aging proprietress of a Kabukicho hostess bar (Atsuko Nakamura, whose character here intriguingly shares both name and occupation with one she played in the otherwise seemingly unrelated comedy, Happy Family Plan), who wishes she could enlarge herself, too, in order to fight by Masuro’s side. We become spectators to his humiliating struggles with his publicity agent (pop and jazz singer UA, who can also be seen acting in Water Woman) over the corporate sponsorships that account for some 60% of his regular income. Most of all, we get a front-row seat as various media scandals engulf Daisato. First his grandfather somehow manages to zap himself huge, and escapes from the nursing home to go on a rampage more embarrassing than destructive. Then Masuro is unable to drive away a pair of Stink Monsters before the mating urge comes over them, so that their copulation is beamed onto every television screen in Japan (or at least onto as many of them as are actually tuned in at a quarter to three in the morning). Finally, in the biggest (but, for Daisato, the most baffling) scandal of them all, seemingly the entire country unites to pillory Masuro when he inadvertently causes the death of the Stink Monsters’ immense yet harmless infant offspring. Hey— he thought he was supposed to kill monsters, right?

Meanwhile, intertwined with all that, there’s what looks at first like the hook for a much more conventional “hero’s redemption” plot. Immediately after destroying the Evil Stare Monster (which wields the extensible eyestalk growing from its crotch like a ball and chain), Daisato is ambushed by a creature called Midon, which resembles a devil with a colossal head, but disproportionately tiny hands and feet. This new monster is completely unknown to Japanese kaijologists (the North Korean government eventually takes credit for it, but who knows whether to believe them?), and it trounces Masuro during their first encounter. The prospect of watching Big Man Japan eat shit and run away gets the public genuinely interested in him for the first time in years, and pressure begins mounting from all sides for Daisato to seek a rematch. He’d rather not do that, though, telling the interviewer that he’s concerned about what would become of his grandpa if anything ever happened to him. Of course, it’s clear enough to everybody that he’s looking out for his own ass as least as much as he’s looking out for the old man’s, but that’s perfectly understandable, all things considered. In a normal movie, the third act would be all about Daisato overcoming his trepidation, and ultimately taking down Midon— perhaps with grandpa’s help, since we’ve already established that he can still make himself big. Big Man Japan hasn’t done anything normal, however, so no one should be a bit surprised that this plot thread culminates in something else altogether.

I’d be a liar if I claimed to understand for certain what that altogether different something was, beyond the starkest example of the phenomenon that I was talking about at the beginning of this review. I do have a hypothesis, though, which I’ll share with you even though it requires me to say say more about the film’s ending than I normally like to. If I’m right, it’s the best way I can think of to communicate how Hiroshi Matsumoto operates throughout Big Man Japan. On the surface, what happens is that Daisato is bailed out of his rematch with Midon by the deus ex machina intervention of a band of heroes we’ve never heard of before, called the Super Justice Family. Imagine that the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers were also the Brady Bunch, and you’ll have the general idea, except that the overall look is more “Ultraman” than “Super Sentai.” But the Super Justice Family’s iconography (stars, stripes, a finishing move that works like kicking a football field goal) and color schemes (various combinations of red, silver, and blue) suggest to me that they’re supposed to be an American hero team, even though there’s no homegrown American tradition of heroes like these. And intriguingly, the moment the Super Justice Family shows up, the whole look of the movie changes. Whereas Daisato and his monstrous foes had previously been rendered by crude but cumulatively charming motion-capture CGI, edited into the most realistic representations of various urban landscapes that the budget would allow, the arrival of the Super Justice Family resets everything to the “rubber suits and miniature sets” paradigm of 20th-century tokusatsu. I think part of what Matsumoto is doing here is to poke fun at the differences between how Japanese special effects techniques are perceived by the home audience, and how they look to viewers abroad. Also— and this is the point at which I go, “Hang on… Is that supposed to be a geopolitical subtext all of a sudden?!”— the Super Justice Family give Midon the most one-sided ass-whooping you can imagine, yet spend the whole fight exhorting Daisato to join in, even though his ostensible contributions make no difference whatsoever. Then they fall to bickering among themselves over why Midon’s curb-stomping wasn’t a flawless victory, and berate Daisato for playing his insignificant part with insufficient enthusiasm. I certainly can’t prove that Matsumoto intended this sequence to comment subliminally on how Japan allowed itself to be harangued into token participation in the George W. Bush administration’s neo-imperialist wars in the Middle East, but I couldn’t help thinking about that once I realized that the Super Justice Family were likely supposed to be Americans.

Again, though, Big Man Japan is enigmatically strange from the very first frame. The interaction of subject matter, tone, and narrative technique yields results that might be conceptualized as “Andrei Tarkovsky’s What We Do in the Shadows.” Masuro Daisato is a taciturn man, protective of his privacy and apt to tell self-serving lies about his personal life; if he were real, he’d be a frustrating interview subject, and unless you know quite a bit about this movie going in, the whole first act is sure to feel annoyingly opaque. It’s hard to tell what we’re supposed to make of the monsters, whose existence is taken totally for granted, and whose motives, assuming they even have any, go unexamined except in the case of the Stink Monsters. What might be the most puzzling thing about them is the human faces that nearly all of them have, pasted via motion capture onto whatever passes for their heads. One naturally expects that to imply a human-like degree of intelligence and interiority, but only the female Stink Monster and her child actually exhibit anything like that. At the same time, though, whenever one of the monsters dies, its spirit is shown ascending into Heaven (amusingly, the Evil Stare Monster’s eyestalk behaves as if it weighs a great deal, even in incorporeal form), so who knows? The jokes cover the entire range from the crudest possible slapstick and scatology (the Strangling Monster can shit javelins!) to social satire so subtle and cerebral that it registers as such only in retrospect. Narrative pace and joke density ramp up in tandem on something like a quadratic curve, in a way that feels like it might itself have been intended humorously. And yet the melancholy note that enters the film at the ramen shop about three scenes in never entirely leaves it, even when Daisato is mopily guzzling wine at the argumentative Super Justice Family’s dining-room table. I don’t know that I’ve ever seen a movie quite like Big Man Japan, and I’m curious now how representative it is of Hitoshi Matsumoto’s style and sense of humor.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact